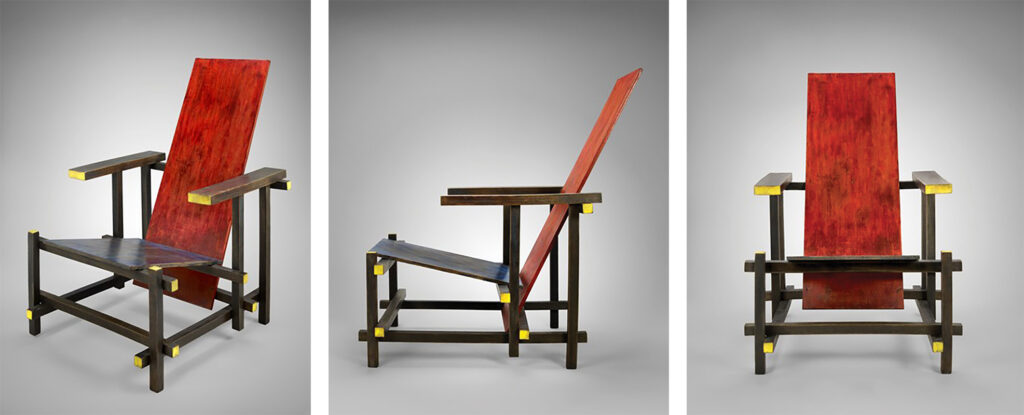

Gerrit Rietveld (Dutch, 1888–1964), Red/Blue Chair, 1918, executed ca. 1922–1923, beech plywood and paint. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase with funds from the Decorative Arts Acquisition Endowment, the Decorative Arts Acquisition Trust, the Friends of the Decorative Arts, and High Museum of Art Enhancement Fund, 2002.256. Photo by Michael McKelvey/courtesy High Museum of Art.

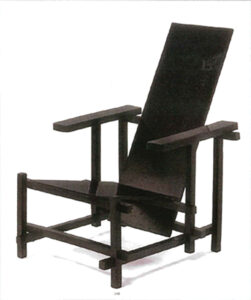

Dutch architect Gerrit Rietved’s (1888–1964) design practice was characterized by paradox. On the one hand, Rietveld was concerned with having his architectural and furniture designs remain conspicuous in order to raise a user-viewer’s awareness of her otherwise habitual activities. On the other hand, Rietveld wanted his objects to function as tools, which generally disappear upon use. Rietveld’s planar armchair (designed ca. 1917–1918) and, more specifically, his Red and Blue Chair (painted ca. 1922–1923) (figs. 1, 2, 3), is exemplary of this paradox.

-

Figs. 1, 2, 3. Gerrit Rietveld (Dutch, 1888–1964), Gerrit Rietveld (Dutch, 1888–1964), Red/Blue Chair, ca. 1920, 33 3/4 × 26 × 33 inches. Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund, 2013.244. © 2015 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Pictoright Amsterdam.

The practice of creating designs that are both useful and aesthetically stimulating is a hallmark of De Stijl, a movement with which Rietveld was closely associated. In 1918, De Stijl comprised a group of painters and architects including Theo van Doesburg (Dutch, 1883–1931), Robert van ‘t Hoff (Dutch, 1887–1979), Georges Vantongerloo (Belgian, 1886–1965), and Piet Mondrian (Dutch, 1872–1944). De Stijl’s first manifesto explained their “new art” as one against the “reign of the individual” and toward the universal. They referred to their work as “the new plastic art” and explained that it was through collaboration that they would “establish international unity in life, art, [and] culture, either intellectually or materially.”1

In the first paragraph of the first issue of their magazine, also called De Stijl, Mondrian expanded on the themes introduced in their manifesto: “The life of contemporary cultivated man is turning gradually away from nature; it becomes more and more an a-b-s-t-r-a-c-t life.”2 De Stijl aimed to draw together the various aspects of art and life into a profound unity. They saw it as their obligation to create works that addressed the realities of the so-called Machine Age and, as a result, to enforce a separation between man and nature to “haste[n] the spiritualization of life.”3

“De Stijl was a typically modernist movement,” writes Yve-Alain Bois, “whose theory was grounded on those two ideological pillars of modernism, historicism and essentialism.”4 According to Bois, De Stijl’s historicism was Hegelian insofar as the members anticipated that their practice would bring about the end of the division between art and life. The associated artists and architects saw themselves as producing an ultimate synthesis, where no aspect of life would fail to be artful and no man would fail to be an artist.5 This expected culmination was a historical project brought about by each art form “realizing” its own “nature” and “purging itself of everything that was not specific to it, by revealing its materials and codes, and in doing so, by working toward the institution of a ‘universal plastic language.’”6 Thus, according to Bois, De Stijl’s historical process was also an essentializing one, insofar as each art form was presumed to have its own nature.

Rietveld’s paradoxical designs should be read in terms of the historical and essentialist ideology characteristic of De Stijl’s larger project as explicated by Bois. De Stijl, though a relatively short-lived and loosely organized group and publication, espoused the idea that art and architecture ought to work together to create a new world. According to the dual principles of historicism and essentialism, the arts would be nonhierarchically integrated to create a totalizing environment where no element escaped integration.7 Bois explains that art needed to be pared down to its essential components—a process he calls “elementarization”—so that the work could be more easily integrated into the larger whole. Bois defines these two operations: “Elementarization, that is, the analysis of each practice into discrete components and the reduction of these components to a few irreducible elements. Integration, that is, the exhaustive articulation of these elements into a syntactically indivisible, nonhierarchical whole.”8 According to Bois’s analysis, to dissolve the incongruities that separate art from life, De Stijl needed all artistic production to be subjected to an encompassing dissection that dissolved anything unnecessary from the work. With each facet of the work at stake, De Stijl artists and architects engaged the ontological foundations of art. For, if they wanted to elementarize some art form, they had to figure out what made it art in the first place and what it was about that art form that separated it from life.9

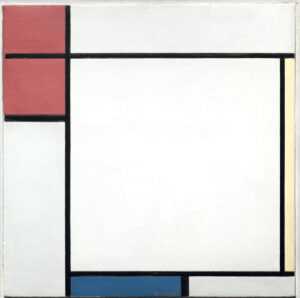

Perhaps the most obvious outcome of De Stijl’s inquiry into an art form’s limits was the integration of a painting’s frame, as seen in Mondrian’s Composition with Red, Yellow, and Blue (fig. 4). In this piece, Mondrian paints to the very edges of the canvas to bring attention to the canvas as the painting’s limit—a feature further emphasized by his use of custom frames. Like Rietveld, Mondrian’s practice of elementarization and integration was paradoxical: by making the frame a conspicuous feature of the work, he collapsed the frame back into the work, thus dissolving its position as the painting’s limit. Rietveld was similarly paradoxical in his method. But where the painter Mondrian addressed the frame-as-limit, architect Rietveld addressed space-as-limit.

In 1932, one year after the death of De Stijl’s founder Theo van Doesburg, and long after artists associated with the group had abandoned the tenets of De Stijl, Rietveld wrote:

Art is not a luxurious excess or, even worse, a kind of spiritual sublimity which stands outside, above or beside society. Art is an important economic factor which creates awareness and sharpens discrimination. Art is not self-sufficient; the words “L’art pour l’art” are degrading as the words “applied art.” Art is action. Art is not a matter of liking [and] is certainly not concerned with the making of beauty; it has no transcendental objective or tendency. The purpose of art is to develop a definite sense organ. Art is the one-sided, yet immediate, experience of reality, the ordinary, simple experience for which we need only open the eyes or extend the hand.10

As this quote shows, the historical and essentialist thinking underpinning De Stijl strongly influenced Rietveld’s writing and thinking well after the group and magazine had disbanded.

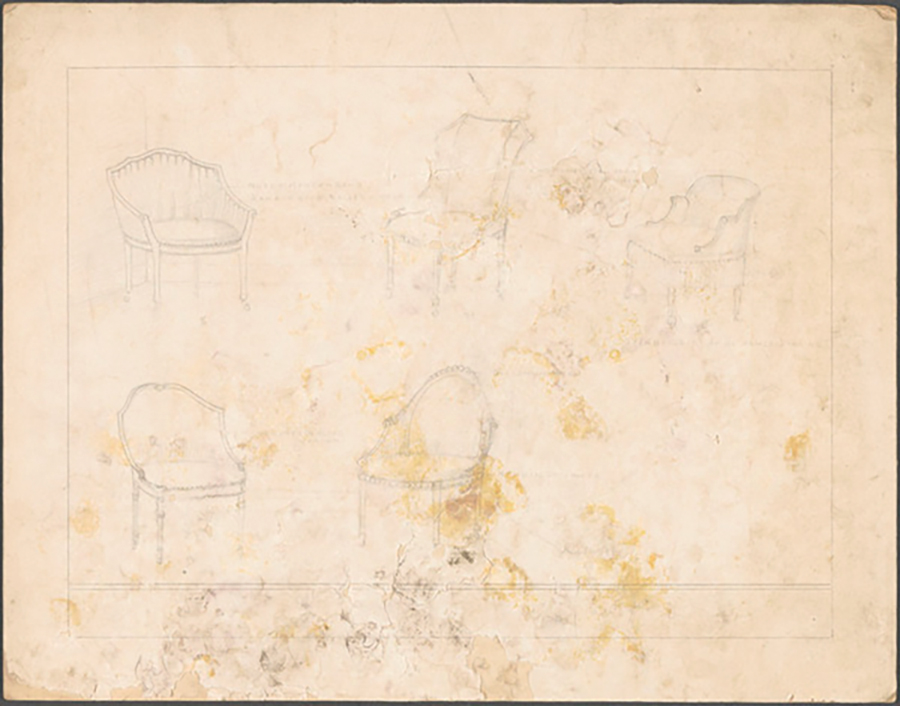

Rietveld’s early involvement with De Stijl in 1918 afforded him the critical distance needed to a break with traditional Dutch culture, a culture of which he was intimately knowledgeable, having dropped out of school at age eleven to work with his father, who was a furniture designer for many of the wealthiest citizens in Utrecht. One of the best-known residences where Rietveld worked designing furniture with his father was Slot Zuylen, a castle just north of Utrecht originally built for aristocrats in the thirteenth century and occupied by the Utrecht elite in the twentieth (fig. 5). Working with his father at the castle was a formative experience for Rietveld. It was here that he developed his skills in traditional furniture design. As early drawings by the architect attest, it was while working with his father that Rietveld became proficient in the production of refined bourgeois designs and with Dutch craft tradition (fig. 6).

-

Fig. 5. Zuylen Castle, Oud-Zuilen, the Netherlands. Photo by the author.

-

Fig. 6. Gerrit Rietveld (Dutch, 1888–1964), Vijf stoelen, 1904–1908, 12 x 15.35 inches, Centraal Museum, Utrecht: Rietveld Schröder Archive.

It was as early as 1911, at age twenty-three, that Rietveld began to distance himself from his father’s workshop and develop his practice elsewhere. He enrolled in an architecture class taught by the modern and experimental architect P. J. C Klaarhamer (Dutch, 1874–1954), where he was urged to think relationally about his practice. Throughout the course, Klaarhamer insisted that his students recognize the subtle but necessary connections that ally design, art, politics, and life. In 1914, Rietveld continued his education in Leiden, where he was introduced to the philosophies of Spinoza, Hegel, Kant, and Schopenhauer, all of whom were operative in his later thought, writing, and design.11

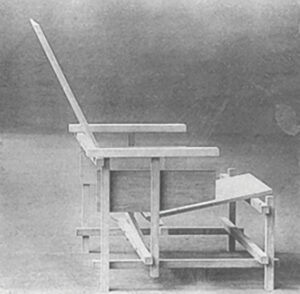

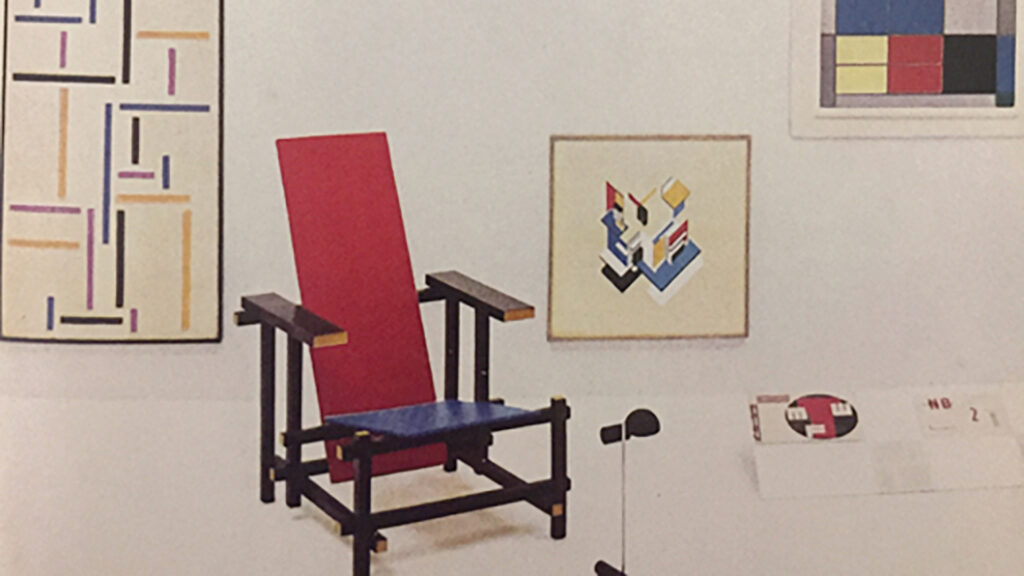

Rietveld’s education transformed his design practice, leading him to reimagine inherited forms like the chair. And in 1917 or 1918 he designed his most famous armchair, what would later become the Red and Blue Chair. It was the design of this early armchair, which was originally unpainted and with side planks under each armrest, that established Rietveld’s reputation and remains among his most memorable designs. Shortly after its completion, Rietveld’s armchair was adopted by De Stijl, who published an image of the chair in their magazine (fig. 7).

Rietveld’s Red and Blue Chair takes up De Stijl’s dictum to end the division between art and life with two paradoxical but key features: its status as both a tool and a spatial abstraction. With his Red and Blue Chair, Rietveld postulates that color and form constitute the means of contact between a human being, her world’s objects, and space. What we see in the Red and Blue Chair—with its three primary colors that distinguish each of the chair’s pared-down components—is Rietveld experimenting toward making space conspicuous for the user-viewer. The explicitness of space—its conspicuousness—moves the user-viewer to become aware of her relationship to the chair. The chair becomes, we might say, strange in capturing the user-viewer’s attention and becoming a salient aspect of her experience. This saliency is important to Rietveld, who is concerned with taking us out of our everyday, passive mode of being-in-the-world.

Consider, for instance, this image, inspired by Martin Heidegger’s Being and Time (1927), written during the same period:

When opening a door, I do not need to think about it. The only time I am aware of such a habitual act is in less-than-ideal or unusual conditions, such as when I am fumbling around in the dark, or when a door is unexpectedly locked or jammed. It is in conditions like these that I ask myself: where exactly do I reach my hand day in and day out? Or, if it is jammed: Do I normally turn the knob left, or right? Do I push or pull? It is often only in these instances, where my everyday way of being-in-the-world has broken down, that I reflect on my interactions with objects in space.

Rietveld, rather than offering a broken doorknob, has attempted to make this same conscious state an integral part of our everyday mode of being-at-home—an activity he calls “dwelling.”12 Rietveld’s Red and Blue Chair attempts to engross our eyes and body by experimenting with our everyday mode of understanding depth, the function of color, and the arrangement of forms. And it is through this experiment that he makes space conspicuous.

Space is perhaps the core concept in Rietveld’s work. It is his means of making art that could intervene in life. Rietveld sees his job as an architect qua artist to make apparent, to solicit our attention toward, that which normally lies in the background of our everyday experience. Rietveld tells us, “Architecture is not a matter of beauty or ugliness, but of clarity.… Good architecture is a fragment of reality which forces a partial expansion of our self.… It is the background of our life, neither more beautiful nor ugly; but if good: clear.”13 What Rietveld wants to do is give “the background of our life” clarity. He wants to do this through the medium of space, which for him is the medium of architecture. Rietveld identifies space as an architectural element that will become central to architecture in its most elementary state. In identifying space as such, and then in thematizing it, Rietveld moves his designs closer toward their total integration with the environment.

For Rietveld, space functions as the frame does for De Stijl painters. Mondrian, for instance, brings attention to the frame in several ways, whether by using custom frames that pull the canvas away from the wall, by creating a second frame within the canvas by leaving the canvas’s edge free of paint, or by painting over the canvas’s edge and bringing the paint up to the literal frame. In each of these instances, Mondrian emphasizes the painting’s status as an “independent entity,” to borrow Bois’s phrase.14 This may seem paradoxical. For, while one might expect the incorporation of the frame to soften the divisions between the work and the space around it, doing so actually reaffirms the painting’s difference. The acknowledgment of the painting’s frame renders that frame more conspicuous and, at the same time, separates the painting from its environment.

Furniture designs do not have a literal frame; instead, they are delimited by their use and position in space. “Characteristic of all architecture,” Rietveld writes, “is that we live in it, on it, around it, and between it.”15 Space, like a painting’s frame, is the fundamental limit of architecture. And, like the frame, space structures our means of identifying an object as such. The “between space” that Rietveld refers to is critical, because it is in the between space (e.g., the space literally between the user-viewer and the chair) that an object is isolated as a distinctive unit.

By including space as a principal feature of the new architecture, Rietveld made the most basic ground of human intuition a prominent feature of his practice.16 In thematizing our being-in-space-with-objects, Rietveld does not merely reverse the normal hierarchy of our experience, where space is empty background to our habitual life; rather, he alters it completely. With the Red and Blue Chair, Rietveld imagines space and objects as, we might say, co-constitutive: I do not experience space without experiencing objects within it, and I do not experience objects without experiencing them in space.

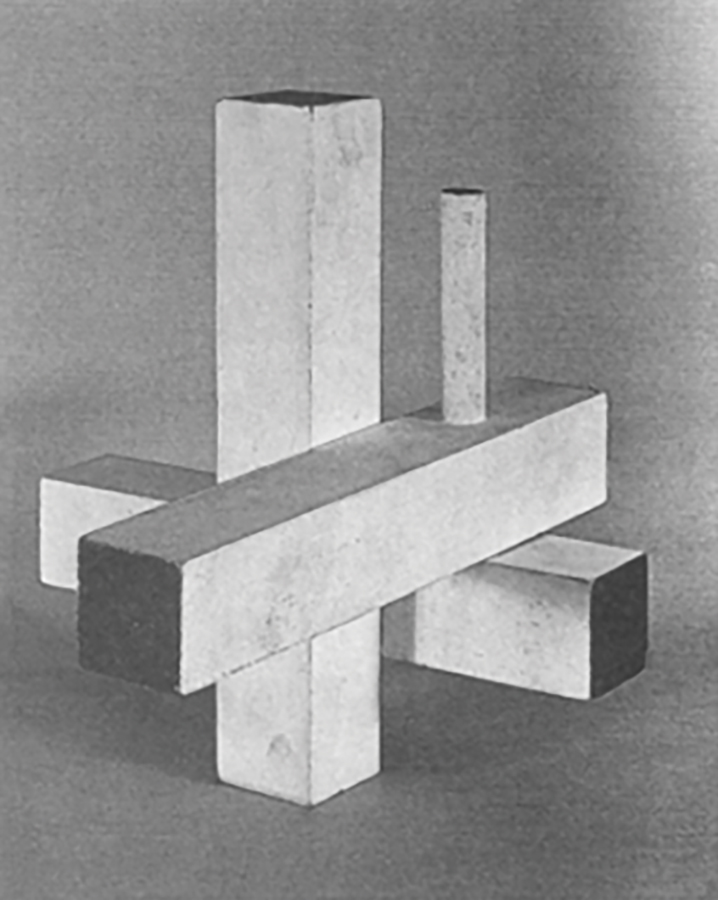

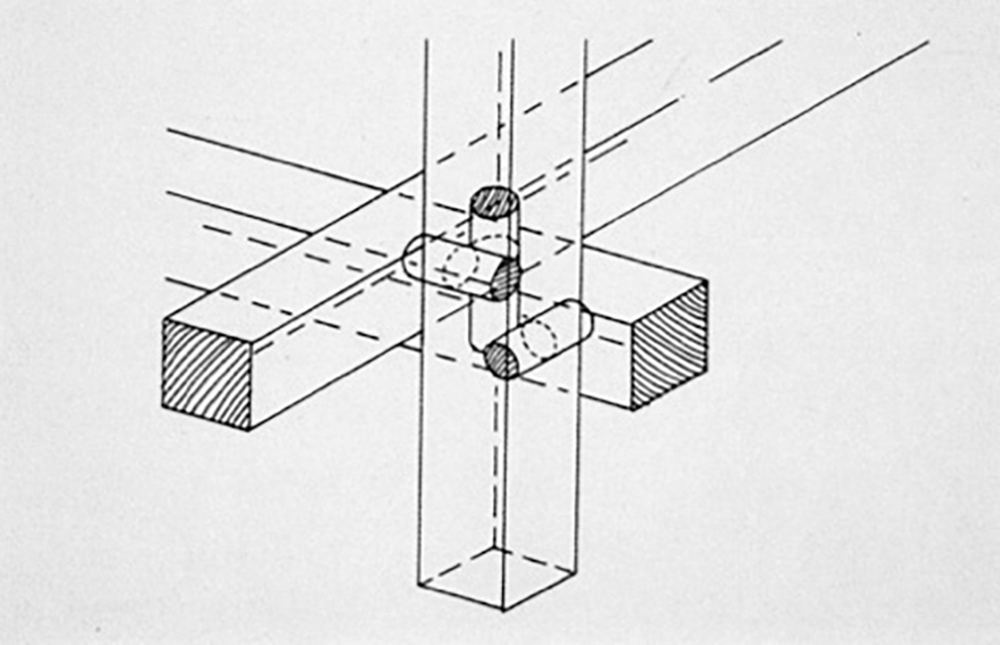

Rietveld’s attitude is built into every detail of the chair. For instance, the Rietveld joint (also called the Cartesian node), used to connect the horizontal laths to the legs by using two vertical hidden dowels and one semi-blind dowel, composes the chair’s most recognized feature (figs. 8, 9, 10). The black-painted laths reach out past the chair’s legs into the user’s space. The laths’ yellow-painted ends highlight the possibility of their extension into the user-viewer’s space while simultaneously emphasizing their finite end. The Rietveld joint is the most acclaimed feature of the chair (a model of it was even included in a 1951 exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam) because it summarizes Rietveld’s larger project. The chair’s form reaches out past its functional necessity into the space between the object and its user, between her and her practical ends. It brings attention to the in-between space that normally goes unnoticed and transforms that into one for embodied experience.

-

Fig. 8. Model of Rietveld Joint, ca. 1950s. Photo: Paul Overy, “Carpentering the Classic: A Very Peculiar Practice. The Furniture of Gerrit Rietveld,” Journal of Design History 4, no. 3 (1991): 140.

-

Fig. 9. Gerrit Rietveld (Dutch, 1888–1964), Red/Blue Chair (detail), 1918, executed ca. 1922–1923, beech plywood and paint. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase with funds from the Decorative Arts Acquisition Endowment, the Decorative Arts Acquisition Trust, the Friends of the Decorative Arts, and High Museum of Art Enhancement Fund, 2002.256. Photo courtesy of the author.

-

Fig. 10. Diagram of Rietveld Joint. Source unknown.

The form of the chair, red and blue or otherwise, is also of central importance. Rietveld has fundamentally reimagined how a chair could look. Seen from its side, the chair is composed of an asymmetrical grid broken by the angle of the seat-back (see fig. 2). A grid can also be seen when looking at the chair head-on. Here, the seat acts as the visual ground from which the grid emanates: the legs divide the seat-as-ground vertically, while the laths divide the ground horizontally (see fig. 3). The grid-structure, combined with the Rietveld joints, have led scholars to compare Rietveld’s armchairs—and the Red and Blue Chair, in particular—to the paintings of Mondrian. These scholars see both works as representations of space if one could carve out a piece of individuated space, which is here being imagined as a Cartesian grid.

While a full account of Mondrian’s practice cannot be developed here, it is sufficient to say that his paintings do not show space as it really is; rather, they recognize that they are ontologically grounded in space. Mondrian’s incorporation of the frame cordons his paintings off from the space around them, affirming the paintings as individuals. Consider, for instance, this quote from Mondrian: “[… architectural space] endures no decoration, since it is in itself a complete space-creating organism, by which all decoration becomes individualization, and therewith limitation, of the universal, i.e., spatial.”17 Mondrian’s conspicuous treatment of the frame, while moving toward the De Stijl ideal of total unification of art and life, simultaneously affirms his paintings as self-sufficient entities. Thus, Mondrian’s paintings are not reaching out into infinite space but showing the limits of painting by incorporating that limit, which, as I have already noted, is the frame.

Similarly, Rietveld’s Red and Blue Chair is not a carved-out unit of grid-space from an imagined Cartesian blanket. In fact, Rietveld does not conceive of space in this way at all: “[U]nlimited space is not visible (and actually does not exist). The spatial value of a tower is that it defines place and measures height, thus making the space around it ‘real.’ Unreflected light does not illuminate space. Material is visible only through its limitation, the separation of material and environment; environment becomes color only through a limited color surface.”18 What Rietveld notes in the first part of the quotation speaks to what I have already discussed above: that the experience of space is only possible between things. While it may exist as a static blanket a priori, its import to Rietveld is bound to its phenomenal qualities, to its ability to make itself, architecture, and design available to the senses. Therefore, the chair is not a part of space “exposed” to the viewer. Rather, the chair is strange because it acknowledges phenomenal space. It does this by reaching out into, and showing, the otherwise vacuous area between the chair and the viewer and transforms that empty area into space—into something of which user-viewers can be conscious. The second part of the quotation adds an important caveat: namely, that color provides both architecture and design (material) its form (distinction) in space (environment). Color is central to Rietveld insofar as it is the mode by which he can make both his designs and the space around them conspicuous.

The body of the chair comprises four legs, two armrests, nine laths, a seat, a back, and, in the earlier version, two side planks. In the case of the Red and Blue Chair, each part is painted to create four groupings. The black-painted armrests, legs, and laths; the blue-painted seat; and the red-painted back are the first three groups, each demarcating a different function. The fourth group contains the yellow-painted ends of the laths, which reach out into the space of the user. The yellow-painted ends are not functional but conceptual—they engage the viewer and bring awareness to the space around the chair. It is Rietveld’s concern with making objects and the space in, around, and between them conspicuous to which I will now turn.

Throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the shape of cities in the Netherlands changed drastically. Metropolises including Rotterdam, Amsterdam, and even the smaller Utrecht saw huge populations of employment seekers move to their centers en masse. Housing was a pressing issue, as the demand for it was not being matched by the private sector’s building. Slums all over the country grew, leaving much of the working class in dire conditions. It was decades before the Housing Act of 1901 took effect, and when funds became available for mass-housing projects, De Stijl’s architects were there to take on the job.

Like their Soviet contemporaries, De Stijl architects seized the opportunity to introduce the public to a spare, modern aesthetic with the utopian faith that their designs would bring about a “spiritual” revolution. While Rietveld was not initially hired as one of these architects, he did see his architectural and design practice as bearing political consequences. Rietveld was an avid follower and supporter of the Russian avant-garde, with whon De Stijl shared much of its ideology. Rietveld’s furniture and housing experiments were meant to be reproducible in a factory setting and enjoyable to make by factory workers.19 However, it was his desire to make his designs conspicuous that most closely allies Rietveld to his Soviet contemporaries.

Rietveld’s affiliation with De Stijl introduced him to numerous prominent members of the international avant-garde, such as Bruno Taut (1880–1938), Walter Gropius (1883–1969), Kurt Schwitters (1887–1943), and László Moholy-Nagy (1895–1946). More than any other member of De Stijl, Rietveld was closest to the Soviets and in fact was one of their most vocal proponents in the Netherlands, hosting numerous Soviet-made film screenings and ensuring the continued availability of their architectural journals in the country. Close to Soviet artists including El Lissitzky (1890–1941), who had a profound influence on van Doesburg20, Rietveld desired to make his designs conspicuous comparable to the politically motivated Soviet desire to make objects active.21

As Russian constructivist Alexander Rodchenko (1891–1956) wrote in 1927, “The light from the East is not only the liberation of workers, the light from the East is in the new relation to the person, to woman, to things.”22 Both the Soviet avant-garde and De Stijl had an interest in amalgamating art and life, and both saw the object, even the mechanically produced one, as a means of making one’s engagement with the object a conscious activity. Rietveld’s designs similarly assert themselves as objects made to be viewed and engaged with actively rather than passively. And, insofar as Rietveld intended his objects to be mass-produced, they were created to make the user-viewer aware of the “relation between human subjects and the mass-produced objects of modernity.”23

Interestingly for a work intended to be mass-produced, no two Rietveld armchairs are the same. They vary in construction, paint color, dimension, and material. Of the forty documented Rietveld armchairs, only about eleven were painted in the now paradigmatic red, blue, yellow, and black ensemble.24 This combination of colors was probably not introduced until the development stages of the acclaimed Schröder House from 1924, about five or six years after Rietveld first built the chair. The High Museum’s Red/Blue Chair (fig. 11) is one of two in the United States in these basic colors and the only one out of a total of five armchairs regularly on display. It is also one of only five red-blue chairs from the 1920s and therefore one of the last to be made by Rietveld himself and one of the first to be painted in the now famed red-blue coloring.

The High Museum’s Red/Blue Chair first belonged to the Dutch painter Jacob Bendien (1890–1933). Since 1924, Bendien had been living with An and Rein Harrenstein-Schräder, who were sister and brother-in-law to Truus Schröder-Schräder (1889–1985), with whom Rietveld worked closely. At some point, the High Museum’s Red/Blue Chair was repainted a dark blue. This was likely executed by Rietveld himself, who in 1926 was hired as an interior designer for the Harrenstein-Schräders and thus for Bendien. While we do not know of many repainted Rietveld chairs, we do know of some.

And we know that Rietveld made and sold several monochrome chairs. This is not to mention many of the unpainted versions Rietveld made throughout his time producing the chair. The 1926 repainting is what accounts for the High Museum chair’s unconventional dating. The chair was likely made around 1922 and then repainted in 1926. The High Museum’s chair has since returned to its original red-blue coloring after having been sold to Christie’s from a private collection in 2002. With small specks of its original color showing through the dark-blue paint, this second layer of paint was removed.

Rietveld constantly reformulated his armchair’s colors and proportions. However, the chair’s shape remained the same after he removed its original side planks (as seen in the image of the chair first published in De Stijl.) Rietveld’s personal armchair (Red Blue Chair, 1919–1920), now in the St. Louis Art Museum, is currently painted completely red, but a close examination of the chair reveals specks of electric blue, white, and yellow paint underneath (figs.12, 13, 14).25 My own examination revealed that the chair was likely painted all white and then repainted electric blue with yellow ends (like those on the High Museum’s Red/Blue Chair) before it was eventually painted all in red. It is possible that the white paint was a primer coat, although it is unlikely because Rietveld usually painted his chairs without primer, especially for the first coat. The most plausible hypothesis is that the chair was repainted by the architect throughout his lifetime in an effort to figure out how best to use color to express his aims.

-

Figs. 12, 13, 14. Gerrit Rietveld (Dutch, 1888–1964), Red Blue Chair, 1919–1920, painted wood, 34 1/4 x 23 5/8 x 32 1/2 inches, Saint Louis Art Museum, Museum Shop Fund and funds given by Mr. and Mrs. Randy Lipton, Director’s Discretionary Fund, the Richard Brumbaugh Trust in memory of Richard Irving Brumbaugh and Grace Lischer Brumbaugh, Alison and John Ferring, Roxanne H. Frank, Nancy and Kenneth Kranzberg, and Susan and David Mesker, 60:2004. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Pictoright, Amsterdam.

Another relevant example of Rietveld’s experiment with the coloring of his armchair is the Red/Blue Chair (ca. 1920) at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Houston’s chair, like the High Museum’s, was repainted at some point, and like St. Louis’s chair, belonged to Rietveld himself. While I cannot speak authoritatively as to why Houston’s Red/Blue Chair eventually was repainted black (fig. 15), I propose that, like St. Louis’s Red Blue Chair and the High Museum’s Red/Blue Chair, it was repainted by the artist, who never was completely satisfied with the chair’s coloring.

A letter from Folkers, Vos & Creman Furniture Conservators in the Netherlands notes that, like the High Museum and St. Louis chairs, the black paint on the Houston chair had begun to chip, revealing the original red, yellow, and blue stains beneath. Conservators were hired to investigate whether the paint could be removed and to learn more about the chair. While chipped paint alone may not warrant a conservation treatment, other findings also confirmed such a need. For instance, the conservators’ 2013 analysis noted that the chair was no longer in stable condition. They described the chair as wobbly, with loose joints and broken nails. They also pointed out that the originally yellow-ended laths had been rounded by a file, likely as a means of making the chair more user-friendly.26

Information regarding the removal of the blue paint on the High Museum’s chair is not currently available, but we may assume that similar measures were used to remove the outermost layer of paint from the High Museum’s chair as were used on Houston’s.27 The Houston conservators used a scalpel to remove sections of the black paint, first at points that would not be easily noticed, until more and more of the red, blue, and black stains were revealed. Once they were certain that the chair was an authentic Red /Blue Chair—and after they had sent paint samples to the Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed, Ministerie van Onderwijs, Cultuur en Wetenschap (Cultural Heritage Agency, Ministry of Education, Culture and Science for the Netherlands, or RCE) for UV-fluorescence and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis—they decided to pursue a complete cleaning.28 That is, they decided to go forward with removing the black paint.

Testing different methods, the conservators found that, while it was easy to remove the black paint with a scalpel from atop the yellow-painted ends, other areas of the chair were not as easily cleaned with the tool. (The conservators wrote that the ease of removing the black paint from atop the yellow was likely due to there being traces of wax on the yellow surface. I propose that, while the wax may have been a factor, the black paint may have come off more easily because they were removing it from another painted, and therefore slicker, surface rather than from a stained-wood surface where the second layer of paint would more fully adhere to the wood.) The conservators then turned to using solvents. Thanks to the now-tested paint samples, they quickly discovered that using solvents would affect both layers of paint and stain because of their similar solubility and because the black paint became soft and sticky. They eventually decided to use a Lynton laser to remove the black paint from the red back and blue seat. In their report, the conservators explained that the paint was easiest to remove from the red surface but that the white primer on the blue paint remained and had to be removed with solvents. They also wrote that the disadvantage of using a laser was the loss of the grease and wax, which resulted in a “very clean red surface.”29 Though the reasons remain unclear, the conservators decided not to use a laser on the black-stained laths. After experimenting with the use of solvents, it was concluded that the “commercial environmentally friendly paint stripper did work the best (Fluxaf Green).”30

The chair was dismantled during the cleaning process. The conservators explained that, because the chair was in such a fragile state and because the original gelatin glue had dried out, many of the joints were easily separated by hand. While the chair was in pieces, they decided to fix many of the now shrunken or broken joints, so that the chair could be put back together more easily and more sturdily. The yellow-painted ends of the laths, which had become worn with age and from the filing, were repainted and re-sharpened. The conservators used gouache paint (likely because of its light finish) for color and Regalrez for varnish. The seat and back were also severely worn, so the conservators decided to treat “both the seat and back … with a coat of Klucel G to consolidate and to saturate the slightly brittle paint” and to use gouache paint in some areas to retouch areas of the chair where it had become “clear that it needed more color.”31

The result is a chair that looks and functions as it would have when Rietveld originally constructed, stained, and painted it in the early 1920s. Comparing Houston’s chair after the conservators’ treatment to another, similar Red/Blue Chair that was also stained in the 1920s, now at the Osaka City Museum of Modern Art in Japan, confirms the conservators’ decisions in cleaning and conserving the chair, for their stains are remarkably close to one another, with the notable difference being Houston’s newer appearance after conservation.

Both the Houston and High Museum chairs bear striking visual and historical similarities: both were likely treated similarly during conservation, were probably repainted by the artist himself (while the primer found on the Houston chair dates to the post-war period,32 the chair was in Rietveld’s family until 1987, and so Rietveld could have easily repainted the chair himself),33 both were made in the early 1920s, and both were originally painted or stained in the De Stijl–inspired colors of red, blue, black, and yellow. Most notably, both chairs were repainted dark colors and, upon their entrance onto the market in the 2000s, were returned to their original coloring.

Without access to the High Museum’s Red/Blue Chair’s conservation report, it is hard to pinpoint what accounted for the decision to remove the chair’s outermost layer of dark-blue paint. Given what is explained in the Houston report, and the state of both chairs before their cleaning, we may conclude that both were cleaned for aesthetic purposes in the hope of increasing their market value. In their original coloring, both chairs fit neatly into any private or museum collection with holdings of De Stijl or De Stijl–inspired art. Moreover, the red and blue coloring is what Rietveld is known for. This is especially true in America. Rietveld’s Red and Blue Chair was reproduced and shown at several important exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), including Cubism and Abstract Art in 1936, Masters of Modern Art in 1954, and Twentieth-Century Design in 1957–1958 (figs. 16, 17, 18).34 For these reasons, collectors and auction houses are willing to invest in extensive cleanings if it means returning the chair to colors that will draw more interested buyers at higher prices.

-

Fig. 16. Cubism and Abstract Art exhibition (installation view), The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1936.

-

Fig. 17. Master of Modern Art exhibition (installation view), The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1954. Photo source: Marijke Kuper, De stoel van Rietveld: Rietveld’s Chair (Rotterdam: NAi Uitgevers/Publishers, 2011), plate 33.

-

Fig. 18. Twentieth-Century Design (installation view), The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1957–1958.

Rietveld wrote in 1920, “I do not make my furniture for the people in the sense that I let the people make demands and deliver judgements (the needs of others). But I myself am one of the people, and I am creating them according to my own needs.”35 Here, Rietveld acknowledges his own idiosyncrasies and the fact that his work is made for and by a single designer. While he affirms his personal commitments, he simultaneously notes that it is only from the collection of individual persons that “the people” is conceivable. As an architect, Rietveld begins from his own needs, his own body, and his own experiences of being-in-the-world-with-objects. The chair, therefore, is for others only insofar as it is first for himself.

Rietveld was always experimenting with the chair (as we have seen with the repainting of his personal chairs now at St. Louis Museum of Art and Museum of Fine Arts, Houston). And, as the quotations included in this paper have shown, Rietveld was committed to De Stijl’s program well after the group had dissolved following van Doesburg’s death. Given the chair’s numerous color schemes, it is clear that the chair’s color was of paramount importance to Rietveld. For even in the cases where the color of the chair was determined by its surroundings, the aim was always the same: to elementarize the chair’s components and to integrate the chair with its environment. Because the chair’s form does not alter much after the removal of the side planks, we can assume that it was by identifying the right color combination that Rietveld aimed to pursue these goals.

Rietveld also used color to bring attention to the space in, around, and between the chair and the user-viewer. Rietveld saw the thematization of space, especially the in-between space, as important to elementarizing and integrating the chair. This practice was paradoxical: thematizing space pared down the chair’s design so that it could be more easily integrated with its environment while simultaneously making the chair and the space around it strange and conspicuous.

Today, Rietveld’s armchair is best known for its yellow-painted ends, combined with the blue, black, and red planes painted differently in accordance with their distinct uses. But, as is shown by the fact that the chair comes in numerous colors, Rietveld was not completely satisfied with this arrangement. We may ask ourselves: What is gained and what is lost by painting a chair all red, as in the St. Louis chair’s case, all black as in the Houston chair’s case, or all dark blue, as in the High Museum chair’s case? And what is gained and what is lost by removing the Houston chair’s black paint and the High Museum chair’s dark-blue paint? Assuming these chairs were repainted for a reason and that Rietveld’s experiments in repainting the chairs were connected to his and De Stijl’s practice of elementarizing and integrating works, then should his red and blue schemes really be valued more highly than others?

Rietveld conceived of the chair as both a “metaphor and metonymy”36 of the human body and simultaneously desired for his chair to be a conspicuous object—what van Doesburg described as an “abstract realistic sculpture of the future interior.”37 The chairs’ various color schemes manifest Rietveld’s investigation into two things: first, into how an object disappears in use and, second, into whether an affording object can retain an aesthetic conspicuousness. Perhaps the Red and Blue Chair veers too far to the side of conspicuousness.

—Courtney Rawlings, Emory University, Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Graduate Fellowship Program in Object-Centered Curatorial Research, 2017

Selected Bibliography

Banham, Reyner. Theory and Design in the First Machine Age. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1982.

Bois, Yve-Alain. “The De Stijl Idea.” In Painting as Model, 101–122. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press,1990.

Broekhuizen, Dolf. “An Awakening of Consciousness. The Early Development of Rietveld’s Theoretical Approach.” In Rietveld’s Universe, ed. Rob Dettingmeijer, Maria Theresia Antoinette Van Thoor, and Ida Van Zijl, 36–47. Rotterdam: NAi Publishers, 2010.

Brown, Theodore M. “Rietveld’s Egocentric Vision.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 24 no. 4 (Winter 1965): 292–296.

De Stijl. “De Stijl: Manifesto I” (1918). In Programs and Manifestos on Twentieth-Century Architecture, edited by Ulrich Conrads, 39–40. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1971.

———. “De Stijl: Creative Demands” (1922). In Programs and Manifestos on Twentieth-Century Architecture, ed. Ulrich Conrads. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1971.

Kant, Immanuel. Critique of Pure Reason. Edited by Paul Guyer and translated by Allen W. Wood. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Kiaer, Christina. Imagine No Possessions: The Socialist Objects of Russian Constructivism. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2005.

Kras, Rayer. “Gerrit Rietveld 1888–1964: Furniture Maker and Architect.” In Gerrit Rietveld: A Centenary Exhibition. New York: Barry Friedman, Ltd., 1988.

Kuper, Marijke. “Rietveld and De Stijl.” In Rietveld’s Universe. Edited by Rob Dettingmeijer, Maria Theresia Antoinette Van Thoor, and Ida Van Zijl, 194–211. Rotterdam: NAi Publishers, 2010.

———. De stoel van Rietveld: Rietveld’s Chair. Rotterdam: NAi Uitgevers/Publishers, 2011.

Overy, Paul. “Carpentering the Classic: A Very Peculiar Practice. The Furniture of Gerrit Rietveld.” Journal of Design History 4 no. 3 (1991): 135–166.

———. De Stijl. London: Thames and Hudson, Ltd., 1991.

Troy, Nancy. “Rietveld’s Modernism.” In Gerrit Rietveld: A Centenary Exhibition. New York: Barry Friedman, Ltd., 1988.