Artistic Personalities and Workshop Practices: Giovanni Francesco da Rimini and the High Museum Madonna Adoring the Christ Child

Laura Maria Somenzi

Fig. 1. Giovanni Francesco da Rimini (Italian, ca. 1420– 1470), Madonna Adoring the Christ Child, ca. 1460, tempera on panel. High Museum of Art, gift of the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, 58.43. Photo courtesy of the High Museum.

Introduction

In 1910, Frederick Mason Perkins wrote in the Rassegna d’arte that the Madonna Adoring the Christ Child (ca. 1460), now at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, “represents in the most complete manner, the artistic character of our painter.”1 The painter in question was Giovanni Francesco da Rimini (ca. 1420–1470), whose artistic character and personality were in the process of construction in the early decades of the twentieth century. It was Corrado Ricci’s brief 1902 article, also in the Rassegna, which published photographs of two panels signed by a Hovanes Franciscus da Rimino, hereunto considered lost, that spurred a rapid and concentrated effort to compile an oeuvre for the quasi-forgotten master.2 Ricci’s paper trail began with the eighteenth-century Bolognese art writer Marcello Oretti, who referred to the two signed panels of 1459 and 1461, which at the time were in the Hercolani Library in Bologna.3 Once the paintings had been located, the gates were opened for scholars to add to Giovanni Francesco’s oeuvre. By 1932, Bernard Berenson had attributed twenty-two paintings to Giovanni Francesco and many more have been added to and dismissed from his corpus since.4

What for the eighteenth century had amounted to a disembodied collection of paintings and documents became for the twentieth century the basis for building a coherent artistic personality whose life and works were stylistically relatable to emerging narratives about fifteenth-century painting. The legacy of connoisseurship that built Giovanni Francesco as an individual from a body of works has proved tenacious: it calls for pause to consider how it is that works such as the Atlanta Adoration prove difficult to write about if not in relation to the stylistic progress of an individual artist.5 The intention of this paper is to offer an alternate avenue for discussing the three Adoration panels gathered under the name of Giovanni Francesco today in the High Museum, the Pinacoteca in Bologna (ca. 1460), and the Tessé Museum in Le Mans (ca. 1455) (figs. 1, 2, 3). By thinking about style in concert with workshop practices and modes of artistic making, it is possible to set aside the kind of stylistic analysis whose purpose is to draw linear progress narratives about a single artist and his conquest—or lack—of what is posited as “true Renaissance” Florentine paradigms.

-

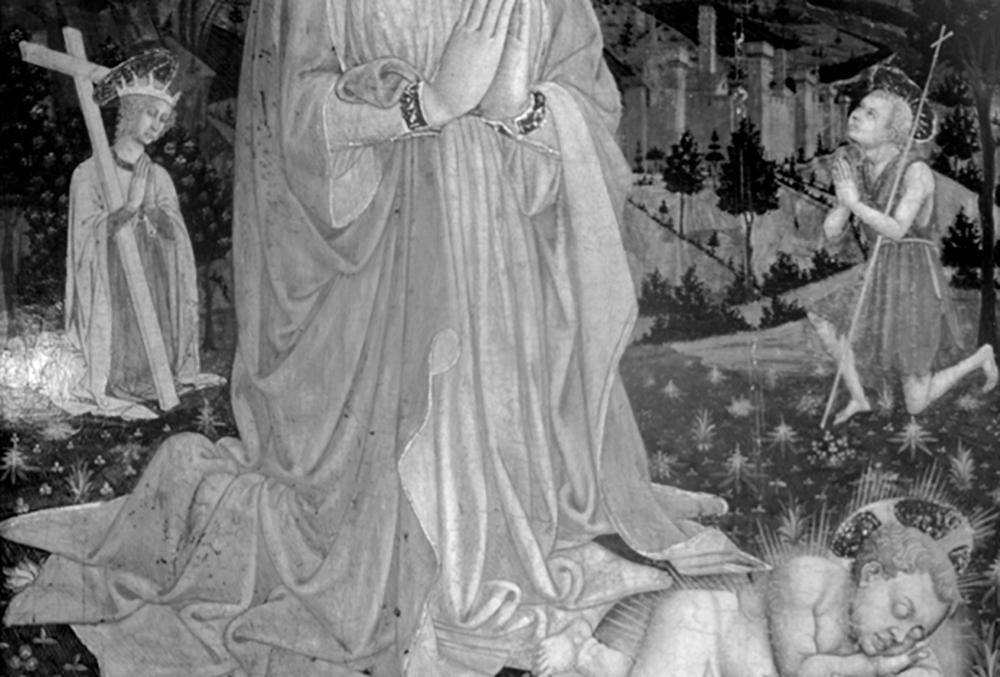

Fig. 2. Giovanni Francesco da Rimini (Italian, ca. 1420– 1470), Madonna Adoring the Christ Child, ca. 1460. Pinacoteca Nazionale, Bologna. Photo: Franco Farranda.

-

Fig. 3. Giovanni Francesco da Rimini (Italian, ca. 1420– 1470), Madonna Adoring the Christ Child, ca. 1455. Musée Tessé, Le Mans. Photo courtesy of the author.

The Atlanta Madonna Adoring the Christ Child

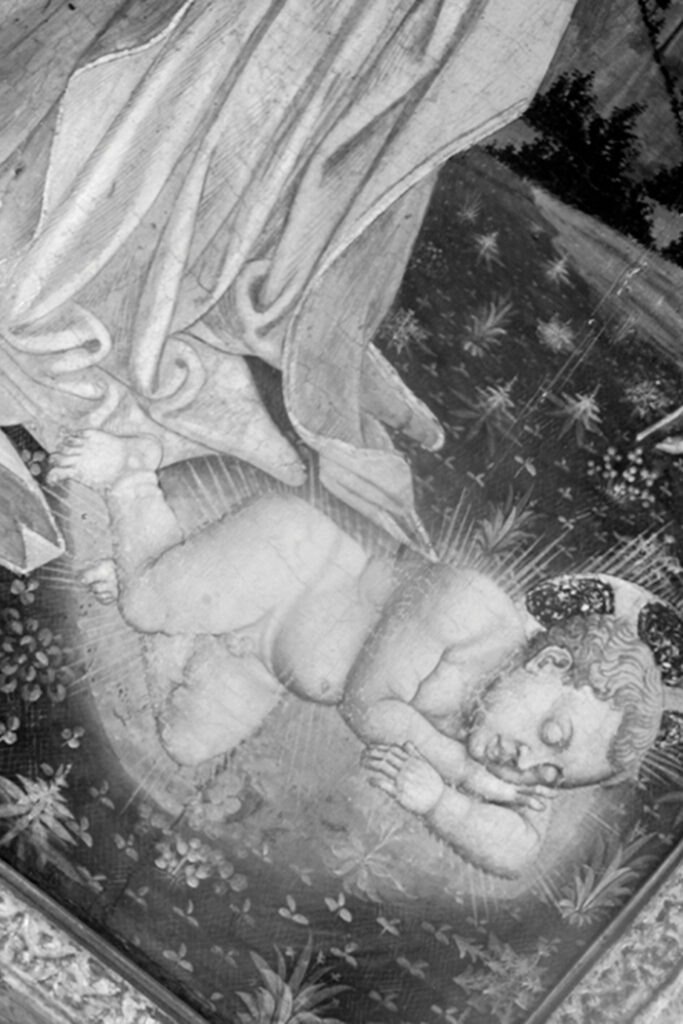

In a field dotted by thistles and dandelions, clovers and plantains, the kneeling Virgin gently presses the tips of her fingers together as she tilts her head and gazes toward the sleeping Christ Child at her feet. Slightly set back on either side of the Virgin, Saint Helena and a young Saint John the Baptist mimic the Virgin’s prayerful gesture. John the Baptist looks upward, as if to recognize the blessing hand of God, which extends past the aureole he shares with two angels to shower gold light onto his Son. In the distance, hills are spotted with small city walls, towers, and churches. At the far left of the panel, a path that spirals around a steep, vertical hill shows two monks: one still walking with provisions over his shoulder and cane in hand, the other at the entrance to a small cave where he kneels in prayer.

Continuing up the hill, small trees are precariously balanced at the profile of the crags, and a large church with soaring steeple dominates the summit. The stillness of the Virgin and saints’ silent adoration for the sleeping Child contrasts with the shuffling action in the background of the traveling monk, chattering birds, and ribbon-like clouds that animate the sky. This peripheral movement accentuates God’s blessing hand, whose gesture is central to the subject of the panel, as he sends his divine favor and recognition to his Son, materialized as ribbons of gold.

Despite the relatively good condition of the panel, the overall tone of the painting would have been much brighter: what are now brown patches in the landscape, likely made with copper cuprite, would have been a vivid green, and the milky sky was intended as the vibrant blue that comes from azurite. Many areas have been inpainted over the years—most notably, the Virgin’s features, parts of the Christ Child’s body, Saint Helena, and God the Father. Layers of varnish, moreover, give the surface a mute gloss. Most significantly, the wood panel has been pared to a shell of its original size and glued to a modern wood cradle. At its thickest point, the panel is 3/16 of an inch, and at its thinnest, 1/64 of an inch. The edges are thus virtually nonexistent, so that about an inch along the edges (normally covered by the modern framing) has been re-painted.6

No records survive of a provenance before the twentieth century for the Atlanta Adoration. We do know that the panel was in the collection of Ing. Corsini in Florence until 1910, when it was purchased by Baron Raoul de Kuffner for his private collection in Castle Diószegh in Hungary (present-day Slovakia), where it remained until 1918. The panel came to New York and was in the gallery of the art dealer Paul Drey until 1946, when it was displayed at the J. B. Speed Museum in Louisville, Kentucky. The Speed Museum did not purchase the panel, and it became a Samuel H. Kress acquisition in 1948 and has since been in the permanent collection at the High Museum.7

When the Atlanta Adoration appears in the scholarly literature, it is often cited as a derivation of Filippo Lippi’s (ca. 1407–1469) Adoration of the Christ Child (1450), now in the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin (fig. 4).8 The combined iconography of Saint Bridget of Sweden’s mystic vision of the Christ Child and the Nativity of Atlanta’s Adoration was arranged into a recognizable type by Lippi about a decade earlier, in the mid-1450s.9 Although the Atlanta panel is in line with this novel combination, the similarity of Lippi’s Adoration to the Atlanta Adoration pertains more to an iconographic rather than stylistic register. And it is certainly not the case that, in imitating Lippi, Giovanni Francesco aspired to a more progressive ideal of a Florentine Renaissance dominated by light and mathematical perspective. To make such an argument is only to reinstate the centrality of a Florentine Renaissance and to graft onto fifteenth-century painting narratives about the progress of art toward modernity.10

From Ricci’s first article on Giovanni Francesco, the oeuvre-building impulse was accompanied by the need to fit the artist within a regional school of painting. For Ricci, the Riminese painter belonged to the Umbrian style of painting, as represented by Benedetto Bonfigli.11 For Raimond van Marle, he was of the school of the Marches, while he retained a certain frigidity from the north.12 All this is to say, he is not quite Florentine and only “pseudo-Renaissance.”13 In Luisa Becherucci’s turn of phrase, “Giovanni Francesco participates [in the Renaissance] both by welcoming gothic lines from the Marches and by brushing up against the great Florentine conquests, in a provincial reduction that is nonetheless artistically coherent.”14

For this line of thinking, no matter how close the artists outside of Tuscany came to being modern and up-to-date, they always retained something of a “poorly dissimulated accent from the periphery.”15 A few scholars allow Giovanni Francesco the label of the itinerant artist, but again only to stage a fortuitous encounter with Tuscan influences, either as a result of a stay in the Medicean city or by way of traveling Florentine-trained artists such as Lippi, Donatello, and Piero della Francesca.16 For others yet, the confusion of regional influences proves hard to bear: “In this zoppesque context, the interlaced threads of the squarcionesque norm, which he had come close to years prior, and of the donatellan construct, brought to clarity by the light of Piero, come to an end.”17

Dizzying as these conflicting regional pulls might be for the reader to follow, one can only suppose that the artist had no choice but to bring an entire stylistic period of his career to a close.

Rather than construe the relationship between Lippi’s Adoration and the Atlanta Adoration as one of progress and derivation, it is more productive to consider how Lippi’s Adoration type was adapted, combined, and reassembled in the Atlanta Adoration. For instance, the Atlanta Adoration shares the devotional focus on the Christ Child with Lippi’s Adoration but instills significant changes. Whereas in Lippi the concentrated attention on the Christ Child is rendered by way of the quasi-impenetrable forest and the tight circular arrangement of figures around the Child, the Atlanta Adoration extends the attitude of prayer across a wider landscape. The Virgin’s prayer is relayed to the middle ground of the painting by the two saints and then brought into the background by the monk. In this manner, the act of the Virgin’s adoration is visually carried, like an echo, throughout the contemporary landscape of Italian hill towns.

In a similar fashion, artists working in the following decades, such as Andrea Mantegna (ca. 1431–ca. 1506) and Carlo Crivelli (ca. 1423–ca. 1495), used the Adoration type as a starting place for elaborating new pictorial inventions. Mantegna’s Adoration of the Shepherds (1455–56), now in the Metropolitan Museum in New York (fig. 5), and Crivelli’s predella panel of the same subject (fig.6) create variations on the Adoration type by setting the Adoration scene within a craggy landscape populated by small animated people who go about various tasks.18

-

Fig. 5. Andrea Mantegna (Italian, 1431–1506), Adoration of the Shepherds, 1455–56, tempera on canvas, transferred from wood. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Anonymous Gift, 32.130.2.

-

Fig. 6. Carlo Crivelli (Italian, 1430–1495), Adoration of the Shepherds, ca. 1491. Musée des Beaux-Arts, Strasbourg.

On the other hand, Crivelli’s Saint George (fig. 7) for the Porto di San Giorgio altarpiece, now in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, presents a further reworking of the setting of the Adoration—rocky landscape, small praying figure on a hill—to update a Byzantine icon type of Saint George slaying the dragon.19 Crivelli also produced multiple Adoration scenes that introduce slight variations from one version to the other. A predella panel of the Nativity (fig. 8) from Crivelli’s Ottoni altarpiece, now in the National Gallery in London, shares many of the same elements—figures, architecture, and landscape—with the Adoration of the Shepherds (see fig. 6). Workshop drawings likely were used to create the ox and ass, as well as the Virgin and Saint Joseph, in both panels. Yet, as Stephen Campbell notes in the recent Crivelli exhibition catalogue, the transfer from one version to the next also introduces noticeable variations.20

-

Fig. 7. Carlo Crivelli (Italian, 1430–1495), St. George, 1470, gold, silver, and tempera on panel. Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, P16e13. Photo courtesy of Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston.

-

Fig. 8. Carlo Crivelli (Italian, 1430–1495), Nativity from Predella of La Madonna della Rondine (The Madonna of the Swallow), after 1491, egg and oil on poplar. The National Gallery, London, NG724.2. Photo courtesy of The National Gallery, London.

The Three Adorations: Atlanta, Bologna, and Le Mans

Multiples were also a part of Lippi’s workshop practice. In addition to the 1450 Berlin Adoration, two panels in the Uffizi in Florence, dated from 1455 and 1463, are clear indicators of Lippi’s consistent reworking of the type (figs. 9, 10). The production of multiples allows us to circle back to the Atlanta Adoration. As previously mentioned, there are three extant Adorations made by Giovanni Francesco and workshop, sometime between 1455 and 1460, now in Atlanta, Bologna, and Le Mans. By thinking about the workshop practices of copying and adapting a type, the relationship between Giovanni Francesco’s and Lippi’s Adoration versions can be reframed from one tied to the achievement of a Florentine standard to one about a shared mode of production.

-

Fig. 9. Fra Filippo Lippi (Italian, ca. 1406–1469), Madonna Adoring the Christ Child, 1455. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.

-

Fig. 10. Fra Filippo Lippi (Italian, ca. 1406–1469), Madonna Adoring the Christ Child, ca. 1463; Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.

Corrado Ricci in 1903, Carlo Gamba in 1904, and Mary Logan Berenson in 1908 brought under the name of Giovanni Francesco the Adoration paintings in Bologna, Atlanta, and Le Mans, respectively.21 These three versions have since been considered within the gradual advancement of Giovanni Francesco’s artistic style: the simpler composition of the panel in Le Mans is followed by the Atlanta panel, which leaves the Bologna version as the most mature example of the artist’s work.22 If one resists a chronological order that narrates the development of a single artistic personality, what comes into focus is what the three panels share in terms of workshop practice.

As a basic configuration, all three panels show the Virgin in adoration of her Child. Her hands are gently cupped in prayer, and she is accompanied in her devotion by attendant figures. In the Bologna panel (see fig. 2), Saint John the Baptist kneels next to the Christ Child, whose sleeping body is propped onto a tree stump and pillow. The ground is rocky and barren, in contrast to the other two versions, and two angles complete the circle of adoration around the Christ Child. In the background, a hilly landscape gives rise to towers and churches, and a small monk kneels in prayer at the mouth of a cave, much like in the Atlanta panel. Whereas the Atlanta panel (see fig. 1) shows a generic church in the background, the church in the Bologna panel has a particular architectural rendering that may very well have had a specific referent. Rather than God the Father, the Bologna panel has Saint Dominic at the apex and two angels below him carrying the arma Christi. Excluding the frames, the painted surface of the Atlanta panel is the largest of the three at 82.6 by 54.6 centimeters; the Bologna panel is 84 by 50.2 centimeters, and the Le Mans panel is the smallest at 34.3 by 24.1 centimeters. The Le Mans panel (see fig. 3) is not only the smallest of the three but is also the most sparsely populated.23 The only figure besides the Virgin and Child is a standing Saint John. As in the Atlanta panel, the figures in the Le Mans panel are situated in a verdant field, and a row of trees divides the figures from the hills and buildings in the background.

While the iconography and individual elements of the three panels are similar, each painting offers a distinct variation in which the combination of figures and landscape is arranged into a different composition. Take, for instance, the figure of Saint John. He is shown standing in the Le Mans panel but kneeling in both the Atlanta and Bologna panels, where he is rotated 180 degrees from the former to the latter. While the various components of Saint John’s attributes—his tunic, with its belt and fur tufts, the gold-patterned halo, and cross staff—are present in all three versions, the actual rendering of these details varies significantly. While it is certainly possible that the Bologna panel has suffered less damage over the years, this conjecture does not fully account for the higher degree of finish and precision when it comes to the modeling of skin, the tight waves of his hair, and the rendering of the different effects of leather and fur tufts. A similar argument can be made for the details of the church in the Bologna panel, such as the side portico supported by slender white columns and the marble-faced doorway, when compared to the generic church architecture in the Atlanta panel.

The differences in painterly execution are especially noticeable between the Atlanta and Bologna Saint Johns due to the high degree of consistency between the poses: back toes tucked under, knee lunged over the front toes so that the heel lifts slightly off the ground, staff leaned against the shoulder, and hands lightly pressed together in prayer. It is most likely that the workshop of Giovanni Francesco had a repertoire of stock drawings and models for figures such as the Saint John. This would account for the commonality of the stock type and the differences in execution. One might even imagine a three-dimensional statuette of Saint John that could easily be rotated to different angles. The process of making the various Adoration versions can also be thought about in terms of stock images and motifs that could be rearranged to various effects and purposes.24 For example, the small monks in the Atlanta panel, one at the cave and the other on the path, seem to migrate in the Bologna panel so that, while one remains at the cave, the other is positioned at the entrance of a church.

These hypotheses follow what we know about fifteenth-century workshop practice and the reuse of cartoons, drawings, and models for executing paintings.25 That the workshop of Giovanni Francesco used cartoons for making paintings is evident on a round panel of God the Father, a fragment from a larger altarpiece, today in the Brooklyn Museum, in which occasional dark dotting lines, or pouncing, from the spolvero transfer technique are visible under infrared reflectography.26 Due to the varying sizes and scales of the three panels, it is not likely that the same cartoons were used for the three Adoration panels. However, this does not preclude that there were other Adoration panels in the workshop of Giovanni Francesco, now lost, which would bear closer evidence of cartoon transfer. Also associated with Giovanni Francesco, a predella panel representing the Nativity (ca. 1455) at the Musée du Petit Palais in Avignon (fig. 11) and a panel of the Baptism of Christ (ca. 1465; private collection) show the possible range and reuse of the models in the Adoration for different contexts and formats. Rather than a direct transfer via cartoons, at their core, the three surviving panels most likely share a stock group of drawings, paintings, or models.

Similar techniques are also traceable between the three panels and point to a common mode of production. Although much of the original gilding has now been lost, the rendering of the halos shows a base level of consistency for how Giovanni Francesco’s workshop crafted gilded ornament. The bole, a red clay with size laid over the gesso preparatory layers of the panel, is now visible where the majority of the gilding has flaked off, especially in the Le Mans panel.27Nonetheless, in the Atlanta and Bologna panels, the halos are both rendered with rays of gold that originate from an invisible central point, which is covered by the top of the Virgin’s veiled head. In all three panels, one can make out the decorative band of vegetal motifs framed on either side by a thin band of gold. Similar ornamental patterns are present on all three panels in places like the sleeves, cloak hems, and halos.

Other similarities in working method are more conjectural due to the highly thinned wood and lack of x-ray imaging to confirm the structure of the wood panels. However, from the painted surface, it is clear that all three versions place the ray of gold emanating from God the Father off-center. Cracks running vertically under the gold in all three panels may indicate that the panel join is located under the gold rays. If this were the case, then it would add to the workshop’s shared compositional strategies in which the structure of the panel forms an underlying system of organization for the pictorial arrangement.28 What can be said with certainty is that even though the painterly execution varies form one panel to the other, the three Adorations share a mode of composition and technical assemblage. Stylistic similarity can here encompass more than a painterly hand to include process and technique. The sharing of a style can thus be understood as a function of a common body of materials, techniques, and tools.

Material Imagination: God the Father Bestowing the Holy Spirit

Thus far, we have considered the transfer of models within the same format of Adoration panels. Also intriguing is the evidence in the Atlanta panel of working across formats and within different frames. A circular panel by Giovanni Francesco now in the Brooklyn Museum (fig. 12) shows God the Father surrounded by angels as he bestows the Holy Spirit, a motif that is echoed in the detail of the Atlanta Adoration representing God appearing in the heavens. The relationship between the painted mandorla in the Atlanta and Brooklyn panels is, however, more than a matter of repeated gestures or figures. While the Brooklyn panel was once a framed element of a multi-panel altarpiece, the tondo motif is assumed into the unified pictorial field of the Atlanta panel in the form of a mandorla. The relationship between the two works on this level prompts consideration of both paintings as material objects. The Brooklyn panel offers a way of looking at Giovanni Francesco’s Atlanta Adoration that includes a sculptural and material imagining of pictorial representation.

Within its original altarpiece setting, the circular Brooklyn panel would have been positioned at the apex of the altarpiece, likely over a central panel of a Madonna and Child.29 Cecilia Cavalca proposes that the central panel would have been the 1459 Madonna and Child (now in San Domenico in Bologna).30 Regardless of the exact panels that would have made up the altarpiece, the pairing of the Brooklyn panel with the 1459 Madonna and Child offers the possibility for envisioning the context for which the panel would have been produced and in which it would have been seen. As much as an altarpiece has painted surfaces that are often privileged in photographic reproduction, an altarpiece is also an impressive and complex material object. Its components, like those of the Brooklyn panel, could be redeployed within different formats, as is the case with the Atlanta painting.

Slightly foreshortened, the mandorla in the Atlanta panel has a three-dimensional presence within the painting that resembles the actual circular wooden panel in the Brooklyn Museum. Given that both were produced in the same workshop, where both the Adoration and the God the Father bestowing the Holy Spirit were recurring types,31 it is possible to conceive of a mode of pictorial representation that begins with the objects in the workshop to create novel compositions. If the Adoration panels combined various figures and types differently from one to the next, the transfer of parts of an altarpiece format into a single panel is yet another way to see the process of assemblage and synthesis at work in Giovanni Francesco’s workshop. The Atlanta Adoration shows how an altarpiece is reimagined into a single panel. When the mandorla is understood as the translation of a physical object, it is no longer necessary to divide so sharply between painterly illusionism and three-dimensional material. Just because the painted surface gives the impression of receding space, it does not mean that illusionistic painting ceases to also have physical presence as a representational mode.

That the mandorla recalls a circular panel at the top of an altarpiece is also intriguing for what it conveys about painting and the devotional imagination. Similar to what Jackie Jung has eloquently argued for the late medieval period, in fifteenth-century Italian painting, visions and visionary experiences were often represented materially or sculpturally.32 This is the case for the Atlanta Adoration in that the vision of the Divine is rendered visible as an altarpiece panel. A related example can be found in Crivelli’s The Vision of the Blessed Gabriele (ca. 1489), now in the National Gallery in London (fig. 13). In Gabriele’s vision, the bodies of the Virgin and Child are rendered in relief against the mandorla in a way that closely recalls contemporary polychrome relief sculpture, such as the numerous sculpted reliefs of the Madonna and Child by Agostino di Duccio (fig. 14), or his tabernacle of the Trinity in Santa Maria delle Grazie, Fornò (fig. 15).

-

Fig. 13. Carlo Crivelli (Italian, 1430–1495), The Vision of Blessed Gabriele, ca. 1489, egg and oil on poplar. National Gallery, London, NG668. Photo courtesy of National Gallery, London.

-

Fig. 14. Agostino di Duccio (Italian, 1418–1481), Madonna d’Auvillers, ca. 1460–65. Musée du Louvre, Paris. © RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY/Photo by Christian Jean.

-

Fig. 15. Agostino di Duccio (Italian, 1418–1481), Tabernacle of the Trinity, 1454–55. Santa Maria delle Grazie, Fornò. Photo courtesy of the author.

By framing the relationship between the Brooklyn and Atlanta panels as one of translating the representation of the Divine from one material format to another, it is possible to reevaluate the stylistic similarities beyond the boundaries of attribution and progress. As each Adoration reused types and motifs to create novel images, the altarpiece format provided the material for imagining visionary experience.

Further Considerations and Conclusions

Many questions remain yet unanswered for the body of works associated to Giovanni Francesco’s name. The connoisseurship that sought to construct a coherent artistic personality whose oeuvre follows a pattern of stylistic progress and traceable influence has its limitations. Under such a rubric, style becomes the grounds for attribution and for the historical reconstruction of an individual who must fit into existing narratives about the history of art: artistic practice, workmanship, and material considerations are marginalized. What I hope to have accomplished in these pages is opening the discourse on paintings such as the Atlanta Adoration to include a rethinking of stylistic similarities within the parameters of making and workshop practices.33

—Laura Maria Somenzi, Emory University, Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Graduate Fellowship Program in Object-Centered Curatorial Research, 2015

Appendix I: Curatorial Choices

The challenge of translating issues of artistic process to museological display are not few. The display of art in modern museums generally favors the viewing of individual works of art as unique and singular productions by individual artists. For premodern works of art, white walls and isolating frames can be deceptive. While working within the framework of the existing exhibition galleries at the High Museum, how might a curator bring workshop practices of making into play for a work such as the Atlanta Adoration? In particular, how might processes of transfer, assemblage, and combination be discussed in relation to the three Adoration panels, and how might the Brooklyn panel best be presented to the museum public? I wish to propose here a few possible exhibition and educational strategies.

One option for the regular display of the Atlanta Adoration would be to accompany the panel with photographic reproductions of the Bologna and Le Mans versions. In this case, the wall text would describe the three paintings as part of a workshop production in which a type—namely, the Adoration—is composed of many variable elements that are selectively redeployed for new compositions. The adjacent text would explain the use of models, drawings, and other material within a workshop for pictorial composition. In addition, the text could call attention to figures such as Saint John, the monks, and the landscape and might ask viewers to consider the ways they remain consistent and the ways they are rearranged. A possible extension could include a hands-on component in which cut-out figures and motifs from the various panels are arranged at a station and paper is provided for tracing and composing one’s own Adoration. This could take the form of a single event, such as a children’s workshop, or a temporary mini exhibition.

A similar strategy could be put into effect for calling attention to the different formats of panel painting produced during the Italian Renaissance. A reproduction of the Brooklyn panel with a trace outline indicating its possible reconstruction as an altarpiece could be displayed alongside the Atlanta Adoration, and the wall label would explain what the formats are and how the altarpiece is adapted in the panel painting. A further challenge in this project would be to account for the fragmentary nature of both panels. However, this would also provide an opportunity to engage the viewer in thinking about the framing of art in modern museums. Such a consideration could also be an opportunity to bring attention to the conservation of the panels and would provide the public with insight on how the paintings have been treated over time with photographs of the cradling and the thinning of the original wood support. An accompanying pamphlet could be produced with this information so as not to overcrowd the wall with text.

Unlike the two Adoration panels, the Brooklyn panel is in a domestic museum. This would facilitate the borrowing of the painting for a focused mini exhibition. In such an exhibition, the goal would be to present two different formats of panel painting and to show how artists used their own productions and materials in different forms. The Brooklyn panel could be displayed on the wall with a line tracing around it that hinted at its original location within an altarpiece. A similar arrangement for displaying fragments of altarpieces without forcing single reconstructions can be seen in the display of panels by Giusto de’ Menabuoi at the Georgia Art Museum in Athens. A station about workshop production, as proposed earlier, could add to the exhibition; educational pamphlets could be produced for the occasion. The aim of these proposals is that of creating a dialogue around the making of Renaissance art and the role of workshop production.

Appendix II: Conservation

The most recent technical examination reports in the Registrar’s file at the High Museum are from 2000 by Charlotte Seifen and Mark Lewis and from 2001 by Charlotte Seifen. In 1949, the blistered pigment was secured, and the panel was mounted and cradled. In 1950, M. Modestini inpainted with dry colors and egg tempera and used a French varnish isolator with a protective coat of Rembrandt varnish plus wax. Conservation notes made by Dianne Dwyer in the mid-1980s state that Modestini thought the painting to have been mounted and cradled in Stephen Pichetto’s studio (Pichetto was curator and trustee of the Kress Collection from 1932 through 1949).34

I was able to observe the painting with conservators Larry Shutts and Renee Stein on three occasions in 2015. Close looking was conducted with raking light, UV light, and reflected digital infrared imagery. Under UV light, considerable cracking can be seen in the faces, and the overall panel is cloudy from the varnish. The painting was removed from the frame, which revealed that the wood panel was thinned to 3/16 of an inch at its thickest, and to 1/64 of an inch at its thinnest. The panel is mounted on a wooden board that is 1/2-inch thick. The varnish, which was a murky color under UV light, was speculated to be polyurethane.

Several places in the painting, such as the Virgin’s lips and hands, have a thin layer of paint that show traces of underdrawing to the naked eye. Digital reflected infrared imagery revealed the layer of underdrawing more fully (fig. 16). The drawing is in close correspondence with the layers of paint. There is also little indication of reworking with the exception of Saint John’s limbs (fig. 17). Hatch marks are most prominently visible in the figure of the Virgin as a technique for building up the modeling of fabric, flesh, and hair. A comparison of the Virgin’s robe with that of Saint Helena shows a simplified use of hatching but also shows the consistent use of curling lines—similar to commas with darkened oval ends—to define the recessing areas of folded cloth (fig. 18). The lines of the cloth fold under the Virgin’s arm are very dark and appear to have been reinforced. The Christ Child, much like a cutout figure, has very sharply defined contours (fig. 19). The treatment of his skin is slightly different from that of the Virgin in that it relies less on hatch marks and more on smudged marks. The background landscape and architecture are also detailed by precise drawn lines. No evidence of pounced dots is visible, but this does not preclude that a transfer technique was used. In a future study, it would be interesting to compare IR images of other panels by Giovanni Francesco with the Atlanta panel to see if there are significant similarities in drawing techniques.

-

Fig. 16. Detail of Madonna Adoring the Christ Child, reflected digital infrared imagery. Photo courtesy of the author.

-

Fig. 17. Detail of Madonna Adoring the Christ Child, reflected digital infrared imagery. Photo courtesy of the author.

-

Fig. 18. Detail of Madonna Adoring the Christ Child, reflected digital infrared imagery. Photo courtesy of the author.

-

Fig. 19. Detail of Madonna Adoring the Christ Child, reflected digital infrared imagery. Photo courtesy of the author.

Selected Bibliography

Bambach, Carmen. Drawing and Painting in the Italian Renaissance Workshop: Theory and Practice, 1300– 1600. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Becherucci, Luisa. Mostra di Melozzo e del quattrocento romagnolo: Onoranze a Melozzo nel V centenario della nascita. Bologna: Stabilimenti Poligrafici, 1938.

Berenson, Bernard. The Italian Painters of the Renaissance. London: Oxford University Press, 1932.

Berenson Logan, Mary. “Ancora di Giovanni Francesco da Rimini.” Rassegna d’arte 7 (1907): 53–54.

———. “Un Quadro di Giovanni Francesco da Rimini al Louvre.” Rassegna d’arte 9 (1908): 163.

Byrne, Donal. “Manuscript Ruling and Pictorial Design in the Work of the Limbourgs, the Bedford Master, and the Boucicaut Master.” Art Bulletin 66 (1984): 118–36.

Cagnola, Guido. “Una nuova opera di Giovanni Francesco da Rimini.” Rassegna d’arte 5 (1905): 127.

Campbell, Stephen J. “Artistic Geographies.” In The Cambridge Companion to the Italian Renaissance, 17–39. Edited by Michael Wyatt. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

———, ed. Ornament & Illusion: Carlo Crivelli of Venice. London: Paul Holberton Publishing, 2015.

Cavalca, Cecilia. La pala d’altare a Bologna nel Rinascimento: opere, artisti e città, 1450–1500. Milano: Silvana Editoriale, 2013.

Fiocco, Giuseppe. I pittori marchigiani a Padova nella prima metà del quattrocento. Venezia: Ferrari, 1932.

Gamba, Carlo. “Firenze.” Rassegna d’arte 4 (1904): 109–10.

Gaye, Johann Wilhelm. Carteggio inedito d’artisti dei secoli XIV, XV, XVI. Firenze: Presso G. Molini, 1839.

Holmes, Megan.“Copying Practices and Marketing Strategies in a Fifteenth-Century Florentine Painter’s Workshop.” In Artistic Exchange and Cultural Translation in the Italian Renaissance City, 38–74. Edited by Stephen J. Campbell and Stephen J. Milner. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

———. Fra Filippo Lippi, the Carmelite Painter. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999.

Jung, Jacqueline E. “The Tactile and the Visionary: Notes on the Place of Sculpture in the Medieval Religious Imagination.” In Looking Beyond: Visions, Dreams, and Insights into Medieval Art and History, 203–40. Index of Christian Art, Department of Art and Archaeology, edited by Colum Hourihane. Princeton: Princeton University, 2010.

Lanzi, Luigi. Storia pittorica della Italia dal risorgimento delle belle arti fin presso al fine del XVIII secolo. Firenze: Sansoni, 1968.

Mantegna, 1431–1506. Edited by Andrea Canova e Antonio Mazzotta. Milano: Officina libraria, 2008.

Minardi, Mauro. “Rivolgimenti e persistenze nel percorso di Giovan Francesco da Rimini.” Arte veneta 54 (2000): 116–25.

Mosso, Valerio. “Giovanni Francesco da Rimini un percorso fra tradizione e rinnovamento nella pittura italiana di metà Quattrocento.” PhD diss., Università di Bologna, 2012. http://amsdottorato.unibo.it/ 5115/1/Mosso_Valerio_tesi.pdf.

Oretti, Marcello. Notizie de’ professori del disegno cioè pittori, scultori ed architetti bolognesi e de’ forestieri di sua scuola raccolte ed in più tomi divise da Marcello Oretti. Biblioteca comunale dell’Archiginnasio, Bologna. Microfilm, ms. B 123.

Padovani, Serena. “Un contributo alla cultura padovana del primo Rinascimento: Giovan Francesco da Rimini.” Paragone 22 (1971): 3–31.

———. Giovanni Francesco da Rimini. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Perkins, Federick Mason. “Altri dipinti di Giovanni Francesco da Rimini.” Rassegna d’arte 15 (1915): 74.

———. “Un altro dipinto di Giovanni Francesco da Rimini.” Rassegna d’arte 10 (1910): 114.

Ricci, Corrado. “Ancora di Giov. Francesco da Rimini.” Rassegna d’arte 3 (1903): 69–70.

———. “Giovanni Francesco da Rimini.” Rassegna d’arte 2 (1902): 134–35.

Rowlands, Eliot Wooldridge. “New Additions and Proposals for the Work of Giovanni Francesco da Rimini.” Paragone 47 (1997): 48–62.

Van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. The Hague: Nijhoff, 1934.

Vertova, Luisa. “Non è Verrocchio.” Antichità viva 35 (1996): 3–8.

Zafran, Eric. European Art in the High Museum. Atlanta: High Museum of Art, 1984.

Zani, Pietro. Enciclopedia metodica delle belle arti; opera del signor Don Pietro Zani, cappellano onorario di S.A.R. il signor infante di Spagna, duca di Parma: manifesto per l’associazione. Parma, 1794.