William Wetmore Story (American, 1819–1895), Jerusalem in Her Desolation, 1879, marble. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, gift of the West Foundation in honor of Gudmund Vigtel and Michael E. Shapiro, 2010.92.

Rome was the geographic center of the nineteenth-century neoclassical art movement, home to an American expatriate community of artists living and working in the Eternal City. The social center of that community was the artist, poet, and critic William Wetmore Story. Story was born into an affluent Massachusetts family, the son of Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story and Sarah Waldo Wetmore. Upon earning his law degree from Harvard in 1840, Story joined the law practice of Charles Sumner and George Hilliard, publishing several significant legal treatises over the next decade.1 A true Renaissance man, however, Story also wrote and published fiction, poetry, and critical essays. It was the death of his father in 1845, though, that unexpectedly launched Story on a career path that would eventually make him an internationally recognized sculptor. Although only an amateur modeler in clay at the time, Story was commissioned to make a memorial for his father to be erected in Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts.2 Fully realizing the limited extent of his artistic abilities, Story moved his family to Rome in 1847 to train as a sculptor. He returned to Boston and his law practice occasionally over the next few years, but the lure of Rome and a profession in the art world kept calling him back to Italy. In 1856, he established a permanent residence in Rome, finally abandoning his law career for good.3

-

Fig. 1. William Wetmore Story, Cleopatra, 1878, marble. High Museum of Art, 2010.89. Photo: Almont Green.

-

Fig. 2. William Wetmore Story, Libyan Sibyl, 1867, marble. High Museum of Art, 2010.90. Photo: Almont Green.

-

Fig. 3. William Wetmore Story, Angel of Grief Weeping Bitterly over the Dismantled Altar of His Life, 1894, marble. Protestant Cemetery. Rome. Photo: author.

Story’s new vocation hit its stride in 1862 when Pope Pius IX sent two of the artist’s ideal sculptures, Cleopatra (1858) (fig. 1) and the Libyan Sibyl (1860) (fig. 2) to the International Exhibition in London as part of the Italian delegation. Both critics and the public praised Story’s works, earning him international recognition.4 Adding to Story’s fame, especially in the United States, was Nathaniel Hawthorne’s evocative description of Cleopatra in his novel The Marble Faun (1860).5 Story continued to earn respect as a sculptor throughout the rest of his career, though none of his later works received the acclaim of Cleopatra and the Libyan Sibyl. For his ideal compositions, he favored emotionally distraught subjects, usually mythological, biblical, and historical women, though he continued to create public monuments and portraits when commissioned.6 Story maintained his sculpture practice until his death in 1895. He is buried with his beloved wife Emelyn in the Protestant Cemetery in Rome beneath a touching monument of his own design, the Angel of Grief Weeping Bitterly over the Dismantled Altar of His Life (1894) (fig. 3).7

-

Fig. 4. William Wetmore Story, Jerusalem in Her Desolation, 1879 (front view), marble. High Museum of Art, 2010.92. Photo: Almont Green.

-

Fig. 5. Jerusalem in Her Desolation (proper left view). Photo: Almont Green.

-

Fig. 6. Jerusalem in Her Desolation (proper right view). Photo: Almont Green.

-

Fig. 7. Jerusalem in Her Desolation (back view). Photo: Almont Green.

-

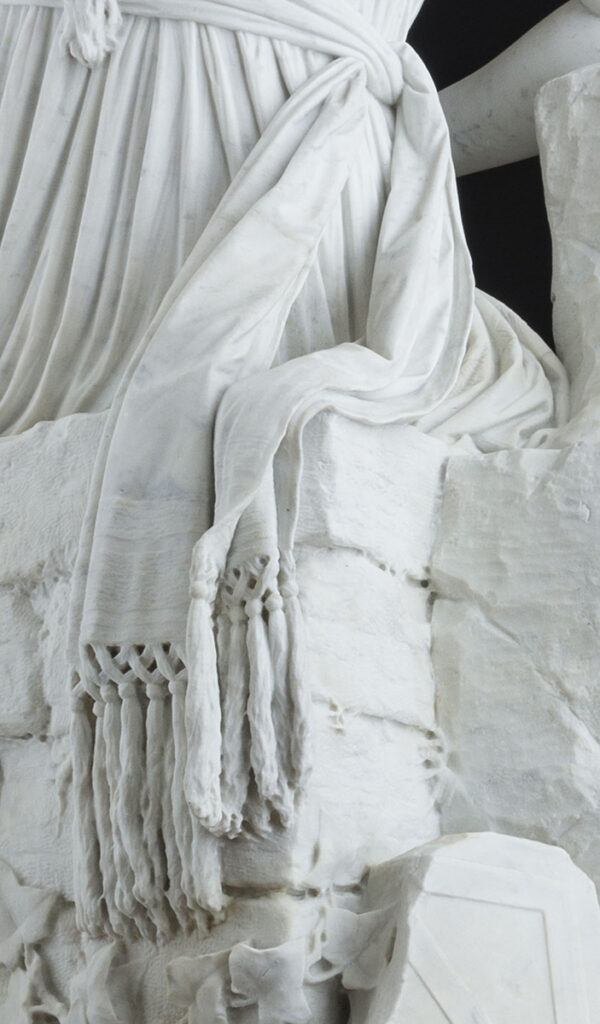

Fig. 8. Jerusalem in Her Desolation (detail of prayer shawl). Photo: Almont Green.

-

Fig. 9. Jerusalem in Her Desolation (detail of head and tefillin). Photo: Almont Green.

Among the distressed, brooding female ideal sculptures in Story’s oeuvre is Jerusalem in Her Desolation (figs. 4–9), first produced in 1873.8 The statue depicts a personifica-tion of the city of Jerusalem resting dejectedly on a pile of architectural ruins. The gray veining in the marble adds to the gloomy mood of the sculpture, evoking streaks of ash from the conflagration accompanying the city’s destruction. Jerusalem wears a sleeveless, classically inspired garment that falls to her sandaled feet, with a separate patterned cloth heavily draped across her lap. A prayer shawl is tied around her waist, while a head covering and tefillin envelop her head and hang down her back (see figs. 8–9). One of Story’s noteworthy characteristics as a sculptor was his attention to archaeological detail, seen especially in the nemes headdress worn by Cleopatra and the Seal of Solomon pendant of the Libyan Sibyl.9 In Jerusalem, such details relate to Jewish iconography and dress to indisputably identify the personification as the Holy City itself. Both the tefillin wrapped around Jerusalem’s head and the prayer shawl around her waist are important symbols of Jewish devotion. A tefillin is a black box that contains verses from the Torah written on parchment. Worshipping Jews place this box in the middle of the forehead at the hairline, encircling the head with the attached straps that then hang down from a knot at the back of the head (fig. 10).10 The straps should drape down from the knot over the worshipper’s chest, but the Jerusalem instead wears them hanging down her back. Traditionally, women were forbidden from wearing tefillin and even today—especially among more conservative sects of Judaism—a woman with tefillin could be accused of cross-dressing.11 In addition to the tefillin, Jerusalem also appears to wear a prayer shawl, or tallit gadol, around her waist. A tallit typically consists of a white woolen shawl with black or blue stripes and white woolen fringes (fig. 11). These ritual fringes are wound in a specific pattern and represent the 613 commandments of the Torah.12 The knotted fringes of the cloth tied around Jerusalem’s waist clearly distinguish it from her other garments.

-

Fig. 10. A Jewish man wears a tallit and tefillin as he prays at the Western Wall in Jerusalem.

-

Fig. 11. Jewish men wearing tallitot as they pray. Photo: Mikhail Levit.

Nancy McClellan Grigg of Paris commissioned Jerusalem in late 1870 or early 1871 for $10,000. Grigg, a distant cousin of Emelyn Story’s, came from a prominent Philadelphia family and intended to donate the work to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, where the original sculpture remains today.13 Count János Pálffy, a Slovakian expatriate residing in Paris, commissioned a slightly smaller version of the statue that was carved in 1877, but dated 1879. Pálffy became a major patron of Story’s work, purchasing at least ten of the artist’s monumental ideal sculptures between 1870 and 1890, including versions of the Libyan Sibyl, Cleopatra, and Saul (1882).14 In 1981, Pálffy’s version of Jerusalem was sold at the Christie’s auction of the World Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma, to the Ponce Art Museum in Puerto Rico. The West Foundation then acquired the statue in 1998 and loaned it to the Georgia Museum of Art at the University of Georgia. In 2010, Jerusalem entered the collection of the High Museum of Art in Atlanta.15

While Grigg as patron likely had some influence on the original composition, other factors certainly influenced Story’s representation of this biblical theme. The subject came directly from the passage of the Lamentations of Jeremiah, which describes King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon’s destruction of Jerusalem in 586 BCE:

How deserted lies the city,

once so full of people!

How like a widow is she,

who once was great among the nations!

She who was queen among the provinces,

has now become a slave.

Bitterly she weeps at night,

tears are on her cheeks.

Among all her lovers

there is no one to comfort her.

All her friends have betrayed her;

they have become her enemies.16

Before its final shipment to Philadelphia in 1873, Jerusalem was displayed at Holloway and Sons Gallery in London, where Story requested that the gallery owners hang quotations from the Lamentations on the walls around the sculpture.17

In addition to the biblical reference that inspired the work, Story’s interest in archaeology and the classical world may have exposed him to ancient Roman representations of a similar subject, specifically the Iudaea capta coins minted under the Roman emperors Vespasian, Titus, and Hadrian. These coins, which commemorated the Roman repression of the Jewish revolt of 66–70 CE, featured a variety of images portraying the personification of the province of Judaea in captivity.18 Most commonly, the coins showed a female captive seated beneath a date palm tree or Roman trophy (fig. 12). The date palm tree served as a geographic reference to the province of Judaea, and the Judaeans themselves used this symbol on their own coins minted during the Bar Kochba revolt of 132–136 CE.19 The woman’s pose clearly communicates her sorrow, as she sits with her head held up by her left hand while her right hand rests in her lap. Story reverses this pose in his depiction of Jerusalem, whose left arm lies in her lap while the right arm leans upon the pile of ruins. Perhaps to further show that a sense of hope or determination dispels some of the figure’s sorrow, Story’s Jerusalem does not dejectedly hold her head in her hands but instead gazes upward into the distance.

A similar theme was taken up by the artist Franklin Simmons, who also emigrated from America to Rome in the mid-nineteenth century and was influenced by Story’s work.20 In his 1874 statue The Promised Land, Simmons closely emulates the Iudaea capta coins by sculpting a Jewish woman leaning against a palm tree with her left hand, while her right hangs listlessly down on her right knee (fig. 13). Elements of Story’s style can be seen in the figure’s seated pose and the inclusion of archaeological details, like the palm tree. The similarity between the two statues and the personification of Judaea on the ancient Iudaea capta coins suggests that both artists may have utilized the same archaeological sources for their respective works.21However, the woman in Simmons’s The Promised Land wears a laurel wreath crown, a symbol of victory awarded in ancient Greek and Roman compositions, signifying her forthcoming triumph: the end of her weary travels and arrival in the Promised Land itself. While Story’s Jerusalem is not as blatantly optimistic as Simmons’s work, her skyward gaze indicates a determination to overcome the despair enveloping her.

Story’s Jerusalem received high praise during its brief sojourn in London, where the Art-Journal remarked upon the statue’s air of “majestic sorrow” and noted the “execution of the work throughout [as] most careful.”22 British writer A. W. Kinglake also viewed the work in London and wrote to Story to express his admiration of the statue, especially “the power with which [he had] forced the cold marble to express glowing flesh.”23 Only a few years later, however, Philadelphia art critic William Clark condemned the Jerusalem for its “stiffness and a total lack of grace … for which there is no reason and no excuse.”24 Further, where Kinglake saw lustrous flesh emerging from icy stone, Albert Gardner of the Metropolitan Museum of Art observed that Story’s monumental female statues sit “heavily draped against their self-generated cold” and derided Story himself as no more than a “gilded amateur.”25 In the artist’s own lifetime, few of his works received the praise and accolades of the Libyan Sibyl and Cleopatra, and his personal letters reveal his concern about his reputation and discontent at his perceived lack of success.26 Perhaps Story’s own melancholic mood was reflected in his somber evocation of Jerusalem.

Story’s penchant for sculpting brooding, romanticized figures, especially women, appealed to the tastes of his age. He was a significant member of a group of American artists living and working in Italy in the nineteenth century.27 These artists often sought inspiration in antiquity for their works, spurred by international fascination with the enigmatic ancient Mediterranean world then quite literally being unearthed by archaeologists.28 Consequently, American neoclassical artists flocked to Italy where they could study the remains of Rome, one of the great ancient civilizations, and reside at the forefront of new archaeological discoveries. Wayne Craven argued that these expatriate artists, in their desire to address their own interest in antiquity, failed to engage with contemporary American cultural and social issues.29 Joy Kasson, however, read the work of these artists much differently, seeing instead a subconscious engagement with nineteenth-century anxiety concerning women and the family.30 Story’s preference for representing powerful women in psychological turmoil perfectly correlates with Kasson’s argument, as does the extensive corpus of similar works created by numerous neoclassical artists of the period. The number of Cleopatras alone produced in various media at the time indicates a recurring fascination with this exotic, doomed figure.31 Americans witnessed significant social, economic, and cultural upheavals in the mid-nineteenth century that caused many people to worry about how these changes would affect domestic life. According to Kasson, the idealized works of the neoclassical artists tapped into this anxiety through the contradictory compositions of formidable women rendered defenseless.32

Story’s Jerusalem illustrates this uneasy theme in its portrayal of the female personification of a great city immobilized by grief within the ruins of her past glory. Similarly, his Medea (1865) depicts the tragic sorceress of Greek mythology not in the midst of her murderous act, but mired within the premeditation of it (fig. 14).33 The inspiration for Story’s Medea was the Italian actress Adelaide Ristori, who performed in Ernest Legouvé’s 1855 adaptation of Euripides’s ancient Greek tragedy.34 In an interesting tie to Kasson’s argument, Legouvé altered the motivation for Medea’s infanticide from revenge against her adulterous husband to an overabundance of maternal affection as Jason and Creusa threatened to take away her children.35 According to Kasson, Story’s images of potentially dangerous women, like the murderous Medea or captivating Cleopatra, presented Victorian audiences with physical manifestations of their fears and anxieties about female nature and the future of the family. Yet, by showing these powerful women arrested in action, melancholic and desperate, he assured his viewers that such dangers could be controlled.36

Kasson’s interpretation offers a valuable context in which to view Story’s monumental female sculptures, but it is limited in its application. Story also created numerous portrait statues and monumental works of historical and mythological figures that do not represent “female power rendered powerless.”37 His frequent dabblings in the spheres of art, literature, and poetry reveal a man with a keen mind and unflagging interest in the history and mythology of the ancient and modern worlds. Jerusalem in Her Desolation exhibits the artist’s passion for archaeology in its similarities with the representations of Judaea on ancient Roman coins and the various symbols of Jewish piety that comprise her costume. Though she is a tragic figure, her upward gaze provides a glimmer of hope, perhaps even of power returning to the powerless, thereby diminishing her despair at the destruction surrounding her.

—Ashley Eckhardt, Emory University, Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Graduate Fellowship Program in Object-Centered Curatorial Research, 2016

Selected Bibliography

Armstrong, Tom, et al. 200 Years of American Sculpture. Boston: D. R. Godine, 1976.

Art-Journal (London) 12 (1873).

Berlin, Andrea, and J. Andrew Overman, eds. The First Jewish Revolt: Archaeology, History, and Ideology. New York: Routledge, 2002.

Butterfield, Andrew. “Story’s Jerusalem in Her Desolation.” Christie’s International Magazine 15, no. 1 (1998).

Clark Jr., William J. Great American Sculptures. Philadelphia: Gebbie & Barrie, 1878.

Craven, Wayne. Sculpture in America. New York: Crowell, 1968.

Curatorial object files. High Museum of Art, Atlanta.

Dio, Cassius. A History of Rome (ca. 1200 BCE–229 CE). 80 vols. 211–233 CE.

Furth, Leslie. “‘The Modern Medea’ and Race Matters: Thomas Satterwhite Noble’s ‘Margaret Garner.’” American Art 12, no. 2 (1998): 36–57.

Gardner, Albert T. American Sculpture: A Catalogue of the Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Greenwich, CT: New York Graphic Society, 1965.

———. “William Story and Cleopatra.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, New Series 2, no. 4 (1943): 147–52.

Gerdts, William H. American Neo-Classic Sculpture: The Marble Resurrection. New York: Viking Press, 1973.

Gold, Susanna W. “The Death of Cleopatra/The Birth of Freedom: Edmonia Lewis at the New World’s Fair.” Biography 35, no. 2 (2012): 318–41.

Hawthorne, Nathaniel. The Marble Faun. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1860.

James, Henry. William Wetmore Story and His Friends: From Letters, Diaries, and Recollections. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1904. 2 vols. 1903. Reprint, New York: Kennedy Galleries, 1969.

James-Gadzinski, Susan, and Mary Mullen Cunningham. American Sculpture in the Museum of American Art of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Philadelphia: Museum of American Art of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 1997.

Josephus, Flavius. Bellum Judaicum. 75–79 CE.

Kasson, Joy S. Marble Queens and Captives: Women in Nineteenth-Century American Sculpture. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1990.

Keddie, George Anthony. “Iudaea Capta, Iudaea Invicta: The Subversion of Flavian Ideology in Fourth Ezra.” Master’s thesis, University of Texas at Austin, 2013.

Kreitzer, Larry. “The Personification of Judaea: Illustrations of the Hadrian Travel Sestertii.” Zeitschrift für die Neutestamentliche Wissenschaft und die Kunde der Älteren Kirche 80, no. 3 (1989): 278–79.

Lynes, Russell. The Art-Makers: An Informal History of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture in Nineteenth-Century America. New York: Dover Publications, 1982.

Martin, Robert K., and Leland S. Person. Roman Holidays: American Writers and Artists in Nineteenth-Century Italy. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2002.

Patterson, Jerry E. “Three Marble Ladies in the Saleroom.” Maine Antique Digest (February 1983): 1B–2B

Phillips, Mary Elizabeth. Reminiscences of William Wetmore Story: The American Sculptor and Author; Being Incidents and Anecdotes Chronologically Arranged, Together with an Account of His Association with Famous People and His Principal Works in Literature and Sculpture. Chicago: Rand McNally, 1897.

Popović, Mladen, ed. The Jewish Revolt Against Rome: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Leiden: Brill, 2011.

Price, Jonathan J. Jerusalem under Siege: The Collapse of the Jewish State, 66–70 C.E. Leiden: Brill, 1992.

Salenius, Sirpa, ed. Sculptors, Painters, and Italy: Italian Influence on Nineteenth-Century American Art. Padova: Il Prato, 2009.

Schäfer, Peter. The History of the Jews in the Greco-Roman World. London: Routledge, 2003.

Seidler Ramirez, Jan. “A Critical Reappraisal of the Career of William Wetmore Story (1819–1895): American Sculptor and Man of Letters.” Ph.D. diss., Boston University, 1985.

Silverman, Eric. A Cultural History of Jewish Dress. Oxford: Bloomsbury, 2013.

Smallwood, E. Mary. The Jews under Roman Rule: From Pompey to Diocletian. Leiden: Brill, 1976.

Stebbins, Theodore E., ed. The Lure of Italy: American Artists and the Italian Experience, 1760–1914. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1992.

Story, William Wetmore. A Treatise on the Law of Contracts. Boston: Little and Brown, 1844.

———. Commentaries on the Law of Agency. Boston: Little and Brown, 1846.

———. Poems. Vol. 1, Parchments and Portraits. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1886.

———. Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Circuit Court of the United States for the First Circuit. 3 vols. Boston: Little and Brown, 1842–1847.

Tolles, Thayer, ed. American Sculpture in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Vol. 1, A Catalogue of Works by Artists Born before 1865. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1999.

Vermeule, Cornelius. Jewish Relationships with the Art of Ancient Greece and Rome. Boston: Department of Classical Art, Museum of Fine Arts, 1981.