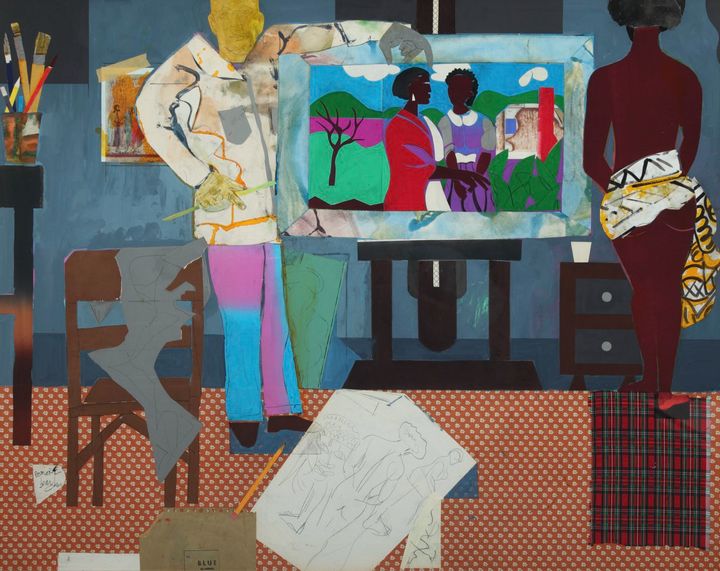

Fig. 1. Romare Bearden, Artist with Painting and Model from Profile/Part II: The Thirties, 1981, collage on fiberboard. High Museum of Art, purchase with funds from Alfred Austell Thornton in memory of Leila Austell Thornton and Albert Edward Thornton, Sr., and Sarah Miller Venable and William Hoyt Venable, Margaret and Terry Stent Endowment for the Acquisition of American Art, David C. Driskell African American Art Acquisition Fund, Anonymous Donors, Sarah and Jim Kennedy, The Spray Foundation, Dr. Henrie M. Treadwell, Charlotte Garson, The Morgens West Foundation, Lauren Amos, Margaret and Scotty Greene, Harriet and Edus Warren, The European Fine Art Foundation, Billye and Hank Aaron, Veronica and Franklin Biggins, Helen and Howard Elkins, Drs. Sivan and Jeff Hines, Brenda and Larry Thompson, and a gift to honor Howard Elkins from the Docents of the High Museum of Art, 2014.66. Photo: Mike Jensen/courtesy of the High Museum of Art.

Memory and metaphor saturate the colorful collages of Romare Bearden’s autobiographical series Profile/Part I: The Twenties (1978) and Part II: The Thirties (1981). Intended as a series of twenty-eight works for exhibition at the Cordier & Ekstrom Gallery in New York, Part I features Bearden’s childhood in the 1920s in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, and Pittsburgh.1 The second installment, Part II, comprising nineteen collages, delves into Bearden’s formative years in 1930s Harlem.2 In collaboration with Bearden, his friend Albert Murray composed accompanying texts for each collage, adding words to the narrative sequence. The impetus for Bearden’s reflective series came from Calvin Tomkins’ interview of Bearden for a 1977 profile in the New Yorker.3 The article examined the life and work of Bearden, from his early days in Pittsburgh to his life in Harlem and time in Paris; Tomkins documented the artistic influences and key figures that played significant roles in Bearden’s development. Profile/Part I and Part II are among Bearden’s later works that explore the social, religious, and musical fabric of his life. In an interview for a 1980 article in ARTNews, Bearden summarized his approach: “I paint out of the traditions of the blues, of call and recall. You start a theme and you call and recall.”4 Employing a musical call-and-response technique in his Profile series, Bearden continually references subject matter from his memories with changing and layered meanings.5 The collages crescendo to his final work, Artist with Painting and Model (fig. 1), now in the collection of the High Museum of Art in Atlanta—his self-portrait featuring an “accumulation of memories,” as described by one Artforum reviewer of the original exhibition.6

In the 1960s, Bearden began to explore the medium of collage and returned to figuration in his art.7 His collages drew from diverse sources, including traditional Chinese painting, Italian Renaissance masterpieces, Dutch genre painting, twentieth-century modernism, and West African sculpture, while peppered with scenes and motifs borrowed from everything from Homer’s Odyssey to twentieth-century jazz.8 Bearden skillfully layered these various influences into complex compositions. Exhibited at the Cordier & Ekstrom Gallery on October 6, 1964, his first collage-photomontage series, Projections, incorporated paper, paint, and photographs into scenes of African American life in Charlotte, Pittsburgh, and Harlem.9 Drawing from his personal experiences, his subject matter revolved around memories of the South, with recollections of picking cotton, watching trains, baptisms, and “conjur women,” and his life in the North, filled with jazz performances and city life. From 1964 onward, he continued to recall themes and motifs from the Projections series; his experiences and memories dominated his collage paintings.10 In the context of his oeuvre, in Profile he used the medium of collage to piece together reconstructions of his own fragmented memories but with universal themes.11

Within his imagery of African American life and culture, Bearden focused on a set of visual motifs, including “conjur women,” trains, and figures engaged in “ritualistic” activities: the musical rituals of blues performances. Bearden imbued “the everyday,” the ordinary people engaged in their rhythms of daily life, with mythic and mystical meaning—they became symbols with a universal resonance.12

Women were a crucial motif in the art of Bearden. They played significant and varied roles as the mother, the lover, or the mystic/magical figure—universal archetypes. The figure of the conjur woman was a constant presence in Bearden’s work. Appearing first in his Projections series was The Prevalence of Ritual: Conjur Woman in 1964 (fig. 2).13 The conjur woman, composed of strips of torn photos and paper, faces toward the viewer, framed by a series of vertical and horizontal lines. She appears in a wooded landscape accompanied by a bird. Imbued with devotional undertones, the composition and her posture recall Renaissance madonnas, attesting to Bearden’s interest in spiritual and religious symbols and gestures.14 The conjur woman was a significant figure in the rural South but also the urban North, particularly in African American communities. She acted as a spell caster and herbalist, with the ability to heal and destroy; her skills made her both respected and feared.15 In texts, she existed as a popular literary trope, likened to voodoo and black magic. In his own experiences from his early years in Pittsburgh, Bearden recalled a conjur woman who cast spells and healed the sick, “an old woman much feared for her power to put spells on people.”16 These primal abilities—her knowledge and her power—resonated with Bearden.17

In Conjur Woman as an Angel, also from the Projections series, she appears in the guise of an angel, facing frontally and engaging the viewer (fig. 3). She attends to a nude woman washing herself in the foreground, while the background illustrates a rural landscape from the South populated with an ox and small cabin. The bucolic countryside situates her within a Southern context familiar to Bearden, but in her form as an angel, she again evokes a religious devotional tone. In this instance, she appears in her guise of a benevolent healer, a force of hope. Bearden recalls his conjur woman with new forms, colors, and styles throughout the 1960s and ‘70s. His 1975 Conjur Woman finds herself in a colorful and densely forested background (fig. 4).18 The figure faces the viewer, a bright red snake wraps around her right arm while a bird (a prevalent motif in Bearden’s art) perches on her left hand, and woodland creatures populate the verdant background. In this new form, the conjur woman is aggressive—she has been reworked into an emblem of evil, shifting away from the sacred tone of the 1964 versions.19

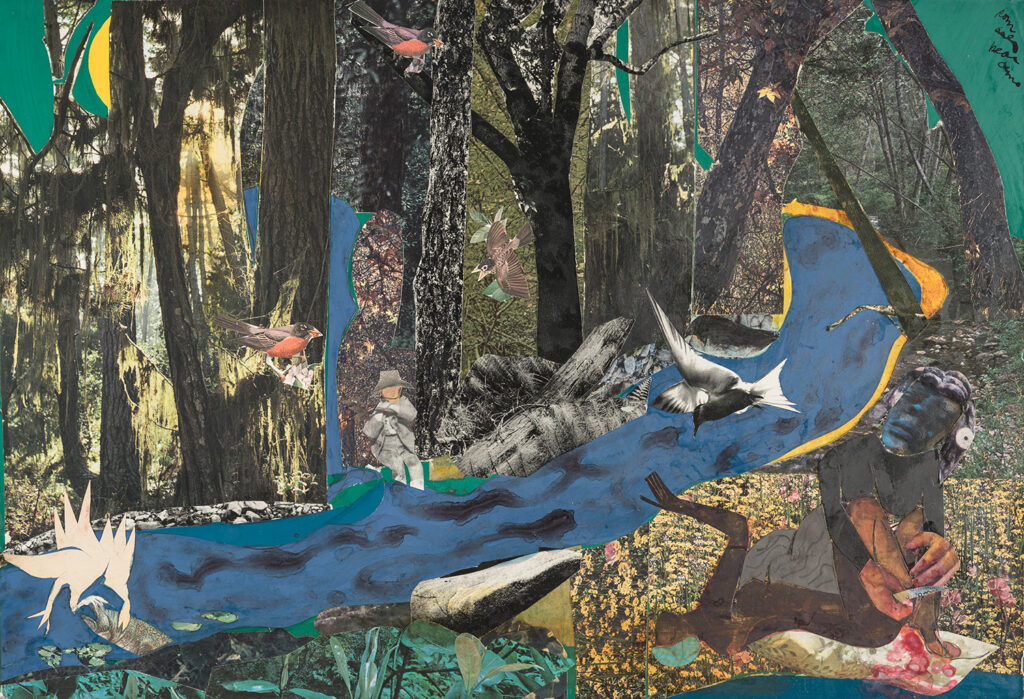

When Bearden introduced a new conjur woman in Profile/Part I, he recalled his past conjur women but with an altered composition and transformed meaning. In the collage titled Conjur Woman & Virgin, a vibrantly blue stream cuts through a wooded forest (fig. 5). A male figure sits along the edge of the river, but the main action occurs in the right corner of the foreground where the conjur woman wields a knife over a nude woman who lies before her, blood streaming forth. The conjur woman of the Profile series sits at the precipice between her roles as healer and the threat of evil.20 “Everything they said a conjur woman could do I believed,” described the text written in chalk on the wall beneath the collage. Murray’s words reference Bearden’s notion of the great powers of the conjur woman. Through image and text, Bearden plucks a familiar character from African American life and builds her up into an archetypal figure of female power that is a force of both good and evil. The Profile series endlessly refers back to the recurring motifs and figures from Bearden’s memories and artistic oeuvre.

-

Fig. 3. Romare Bearden, Conjur Woman as an Angel from Projections, 1964. Private collection. Photo: Schwartzman 1990, p. 214.

-

Fig. 4. Romare Bearden, Conjur Woman, 1975, collage with spray paint on paper. Allen Memorial Art Museum of Oberlin College, R. T. Miller Jr. Fund, 2001.3. Photo: Fine 2003, no. 97.

-

Fig. 5. Romare Bearden, Conjur Woman and Virgin from Profile/Part I: The Twenties, 1978, collage with ink on fiberboard. The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, Museum purchase, 1997.9.13. Photo by Zalika Azim, courtesy of The Studio Museum in Harlem.

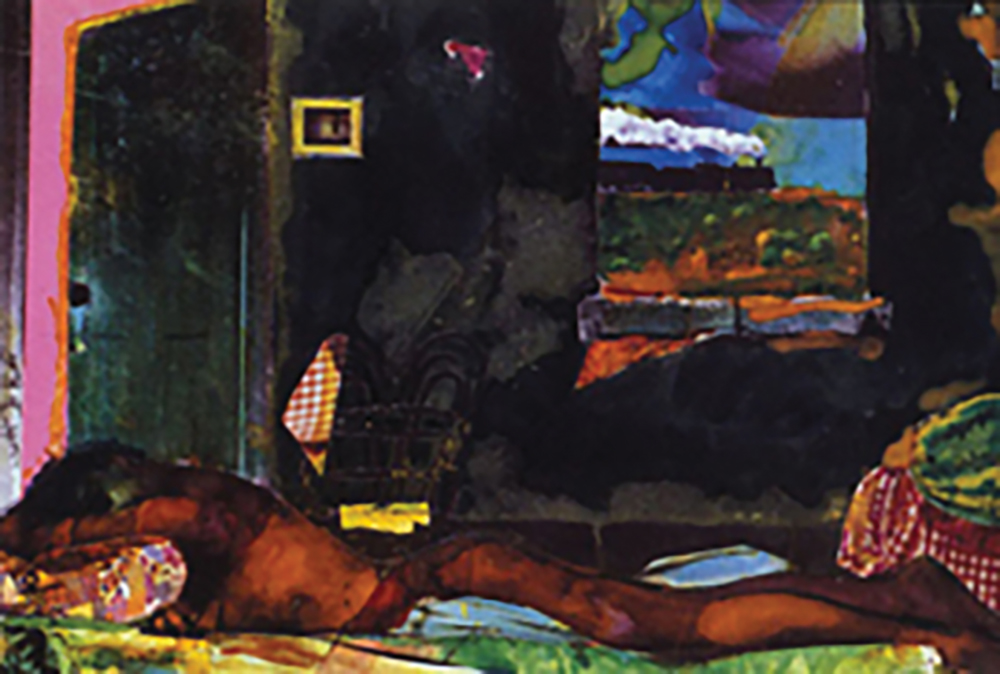

Another central motif at the heart of Bearden’s collage paintings is the train, which appears with particular frequency in Profile/Part I. The names of the trains/collages signal the time of day as they race through various landscapes in the South: Daybreak Express, The Afternoon Northbound, Sunset Limited, and Moonlight Express (figs. 6, 7, 8, 9). Marking the time as the day passed, the train moves across the background as figures engage in the rituals of daily life in the South.21 While the latter three scenes occur outdoors in the rural countryside, Daybreak Express invites the viewer into an interior space where a nude woman reclining along a bed dominates the foreground. Through the window of the room, a train passes by, a puff of smoke billowing behind it. The accompanying text reads, “You could tell not only what train it was but also who the engineer was by the sound of the whistle.” As a child, Bearden would watch the trains go by day and night, sometimes walking down to the Southern Railroad station with his grandfather in Charlotte to watch the trains come in.22 The whistle of the train would have been a familiar sound, preserved in his memories. Before the Profile series, Bearden incorporated trains regularly in his collages and titles such as Watching the Good Trains Go By (1964), Southern Limited (1976), and Evening Train to Memphis (1976), and he would continue to recall the train in later works such as Sunset Express (1984). Trains often appeared through windows and opened doors of interior spaces, as in Daybreak Express and Sunset Express, or in the distance in outdoor scenes (fig. 10).

-

Fig. 6. Romare Bearden, Daybreak Express from Profile/Part I: The Twenties, 1978, collage on board. Private collection. Photo courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington.

-

Fig. 7. Romare Bearden, The Afternoon Northbound from Profile/Part I: The Twenties, 1978. Private collection. Photo courtesy of the Romare Bearden Foundation.

-

Fig. 8. Romare Bearden, Sunset Limited from Profile/Part I: The Twenties, 1978, collage on board. Collection of Ute Stebich. Photo by Paul Takeuchi.

-

Fig. 9. Romare Bearden, Moonlight Express from Profile/Part I: The Twenties, 1978, collage on board. Collection of Barbara B. Millhouse. Photo by Paul Takeuchi.

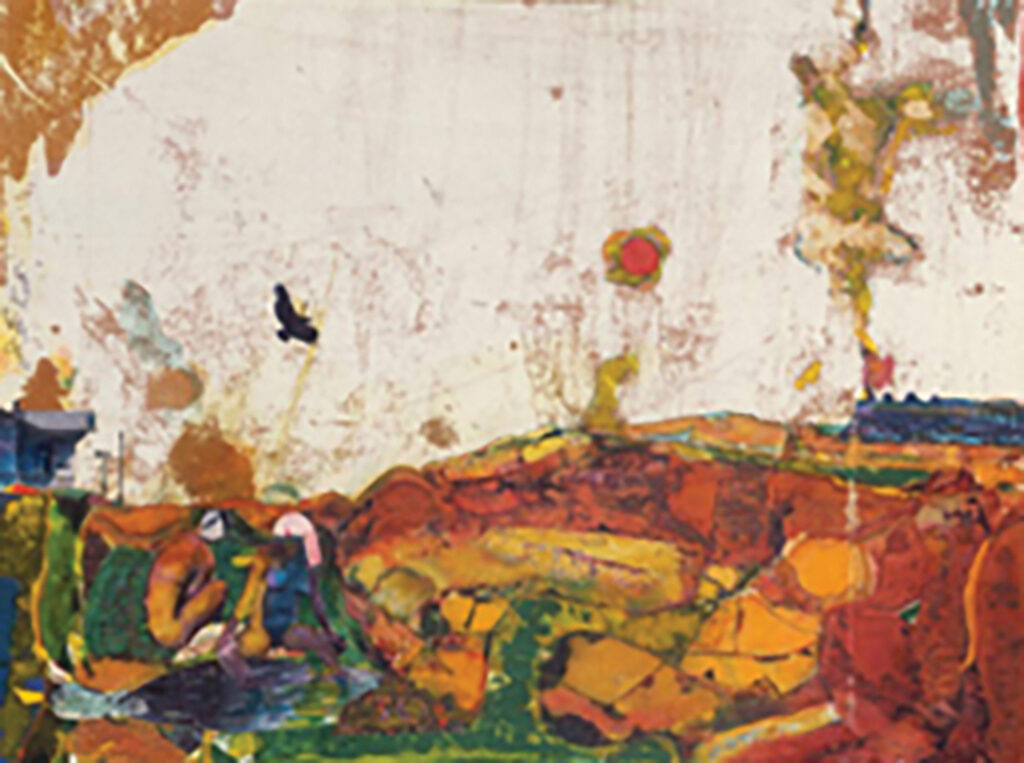

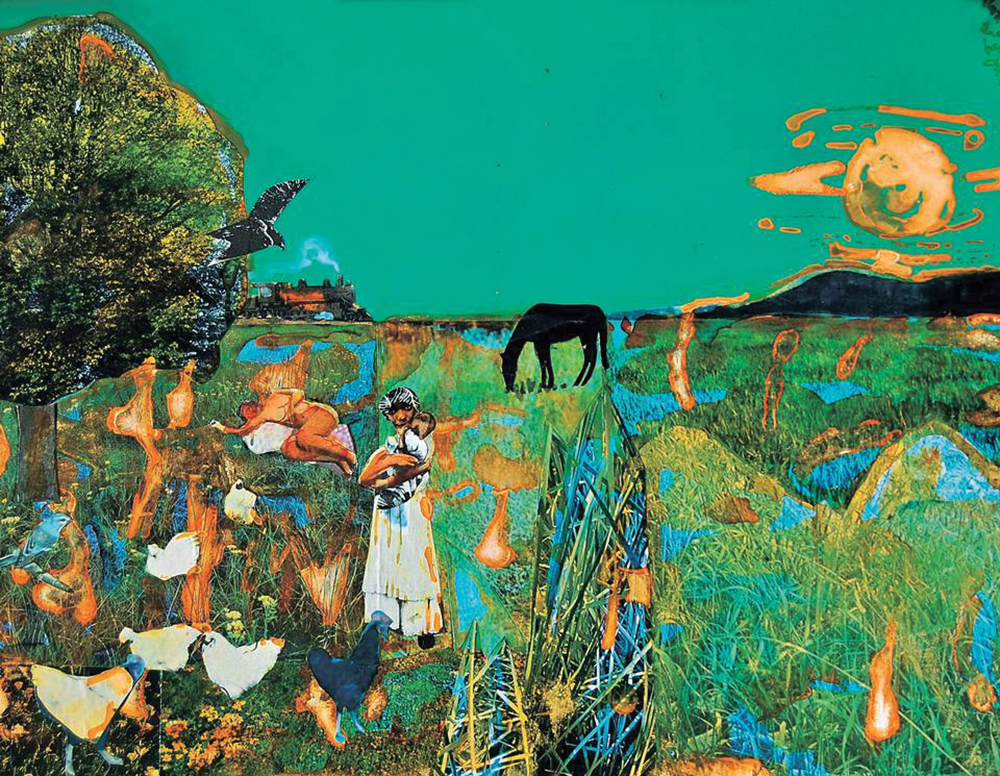

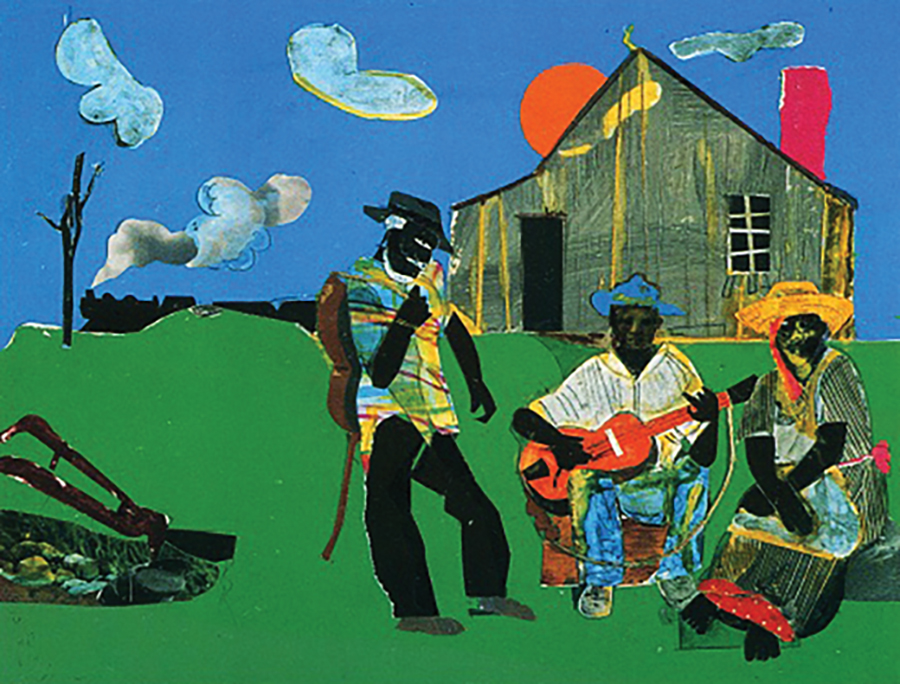

The train played a crucial role in the life and memories of African American Southerners. Bearden described “the train as a symbol of the other civilization—the white civilization and its encroachment upon the lives of blacks. The Train was always something that could take you away and could also bring you to where you were.”23 Trains were also the means by which African Americas moved to the North during the Great Migration of the early twentieth century. In many of his collages, trains suggest the transition from a rural South to the urbanized North.24 Three collages at the beginning of Profile/Part II include trains running in the background: Mr. Jeremiah’s Sunset Guitar, Prelude to Farewell, and Pepper Jelly Lady (figs. 11, 12, 13). In the latter two images, Bearden explicitly references the train journey up north to the industrialized cities in his accompanying texts. Bearden’s trains may have also functioned as a more universal metaphor for change.25 The inclusion of the trains particularly early in his personal narrative in the 1930s could signal the transition from his early years in Mecklenburg in the South (Part I) to his life in Harlem in the North (Part II).

-

Fig. 10. Romare Bearden, Sunset Express, 1984, collage on board. Asheville Art Museum, Asheville, NC, Museum Purchase, 1985.04.1.29. Photo: Schwartzman 1990, p. 21.

-

Fig. 11. Romare Bearden, Mr. Jeremiah’s Sunset Guitar from Profile/Part I: The Thirties, 1981, collage on board. Collection of Jane and Raphael Bernstein, Ridgewood, NJ. Photo courtesy of the Romare Bearden Foundation.

-

Fig. 12. Romare Bearden, Prelude to Farewell from Profile/Part I: The Thirties, 1981, collage. The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, gift of Altria Group, Inc., 2008.13.2. Photo by Marc Bernier/courtesy of The Studio Museum in Harlem.

-

Fig. 13. Romare Bearden, The Pepper Jelly Lady from Profile/Part I: The Thirties, 1981, collage on board. Collection of Joy and Larry Silverstein. Photo by Peter Harholdt.

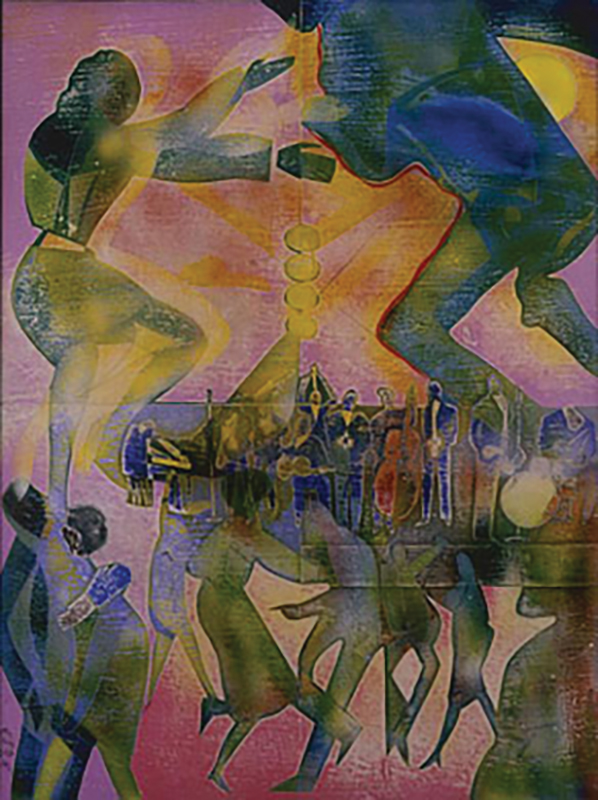

Profile/Part II: The Thirties embraces a new set of imagery of life in Harlem—cityscapes, jazz performances, and urban rituals dominate. Reflecting on the 1930s, the metropolitan landscape of New York provided rich material for Bearden’s art. Absorbing the vibrant sights and sounds of the Harlem dance clubs, Bearden, beginning in the 1960s and onward, would recreate his memories in hundreds of works in collage, mural, and mosaic.26 In the 1970s, Bearden focused more closely on the theme of music, leading to monotypes and several exhibitions that expressed his interest in jazz and blues. These “musical ceremonies” for Bearden were part of the rituals of daily life—especially for African Americans—and they were a continuation of the tradition of blues musicians from his childhood in the South.27 Several series by Bearden before Profile/Part II capture the influence of jazz music and New York, such as his 1975 series, Of the Blues, exhibited at Cordier & Ekstrom.28 From the Of the Blues series, At the Savoy and Wrapping it Up at Lafayette (1974) illustrate two significant music and dance venues, the Savoy Ballroom and the Lafayette Theater, both located in Harlem (figs. 14, 15).29 The collage-paintings feature loud colors that convey the vibrancy and urgency of the music and dancing. In the evenings, Bearden and his circle would frequent places like these, which let artists in for free and where the great bands of the time played.30 Bearden revisited these Harlem venues in several collages in Profile/Part II. Johnny Hudgins Comes On employs bright colors: saturated pinks, reds, blues, greens and yellows abound (fig. 16). A central figure, presumably Hudgins, adorned with a top hat and bow tie smiles out at the viewer while gesturing to the large sign that reads, “Lafayette.” Beneath the colorful banner, a group of musicians perform, while to the far left stands a woman dressed to the nines. The accompanying text by Murray reads, “He was my favorite of all comedians. What Johnny Hudgins could do through mime on an empty stage helped show me how worlds were created on an empty canvas.” Music, performance, and Harlem played significant roles in shaping the work of Bearden, who consistently drew upon his memories and earlier art series for his Profile collages.

-

Fig. 14. Romare Bearden, At the Savoy from Of the Blues, 1974, collage of various papers with paint, ink, and graphite on fiberboard. Collection of Raymond J. McGuire. Photo: Fine 2003, no. 70.

-

Fig. 15. Romare Bearden, Wrapping It Up at the Lafayette from Of the Blues, 1974, collage, acrylic, and lacquer. The Cleveland Museum of Art, Mr. and Mrs. William H. Marlatt Fund, 1985.41. Photo courtesy of The Cleveland Museum of Art.

-

Fig. 16. Romare Bearden, Johnny Hudgins Comes On from Profile/Part I: The Thirties, 1981, collage and mixed media. Collection of Rick and Monica Segal. Photo courtesy of Rick and Monica Segal.

While the majority of his collages in Profile more explicitly call and recall past material and subject matter, the final piece, Artist with Painting and Model, is an unparalleled artist self-portrait. Murray’s text sets the scene: “Every Friday Licia used to come to my studio to model for me upstairs above the Apollo Theater.” Bearden invites the viewer into his studio above the Apollo Theater in Harlem, circa 1941. He stands in the middle of the studio, one arm draped over a painting on an easel, recognized as his 1941 gouache on paper, The Visitation, the other hand grasping his paintbrush.31 A nude woman, identified as his favorite model, Licia, poses with her back turned. Littered on every surface—floor, table, chair, wall—are paintbrushes, pencils, and scraps of paper, references to Bearden’s artistic practice. Scholars have mined the studio for meaning: a reproduction of Duccio’s Road to Emmaus on the wall behind Bearden references his study of the Renaissance masters; a pencil drawing on the floor shows his interest in the female nude and African masks, indicating the influences of African and modern avant-garde art; the batik textile draped over Licia further references the importance of African art; and the discarded paper draped over the chair features a cutout that matches the shape of Bearden’s left hand.32 Layered with fragments of his artistic practice and past, the collage is a veritable collection of memories.

Bearden’s reference to The Visitation on the painter’s easel recalls the period in the 1940s when he began to draw upon Southern themes for his gouache on brown paper paintings (of which some twenty were made) in his phase as a social realist painter (fig. 17).33 Renaissance artists imagined the biblical story of the visit of Mary with her cousin Elizabeth in numerous paintings, but Bearden reworked the scene with two African American women in a rural North Carolina setting of his childhood. His original 1941 tempera on paper features earthier, more muted tones of browns, greens, and reds; the angular features, almost sculptural in quality, of the massive faces of the women recall the style of African masks and Mexican mural painting.34 A biblical story, early Renaissance paintings, Mexican murals, African art, modernist aesthetics, and his own memories of the South provide manifold layers of influence on his painting.35 The appearance of The Visitation in his self-portrait references, like the scattered motifs in his studio, his artistic development as he drew upon rich and varied sources. The inclusion of The Visitation in particular marks the point when Bearden first began to use his childhood memories as artistic material.36 Artist with Painting and Model thus references not only Bearden’s personal experiences but also the very moment when he began to use his memories in his artwork—Bearden had come full circle.

In Artist with Painting and Model, the copy of The Visitation plays the part of the “call and recall” that Bearden continually embeds in his collage-paintings.37 In contrast to the original, the quoted Visitation adopts the aesthetic of his vibrantly colorful collages of the early 1980s with an emphasis on cutout shapes pieced together. With each repetition, the formal qualities shift, and the subject matter gains another layer of meaning as it is reinterpreted. His conjur women, trains, jazz performances, and self-portrait recall old themes in new manners. Through layered memory and metaphor, the Profile series celebrates the distinctive use of collage and repetition in the art of Romare Bearden.

—Julianne Cheng, Emory University, Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Graduate Fellowship Program in Object-Centered Curatorial Research, 2016

Selected Bibliography

Berman, Avis. “Romare Bearden,” ARTNews. (1980): 60–72.

Campbell, Mary S. “History and Art of Romare Bearden.” In Memory and Metaphor: The Art of Romare Bearden. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

———. “Romare Bearden: A Creative Mythology, Part I.” PhD diss. Ann Arbor, MI: University Microfilms International, 1982.

Corlett, Mary Lee. “No Star is Lost at All: Repetition Strategies in the Art of Romare Bearden.” In Romare Bearden: Southern Recollections. Charlotte, NC: The Mint Museum, 2011.

Fine, Ruth. “Nurtured and Necessary: Mothers of Invention.” In Romare Bearden, American Modernist. Edited by Ruth Fine and Jacqueline Francis. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2011.

———. “Romare Bearden: The Spaces Between.” In The Art of Romare Bearden. Edited by Ruth Fine. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2003.

Gilmore, Glenda Elizabeth. “Romare Bearden’s Mecklenberg Memories.” In Romare Bearden: Southern Recollections. Charlotte, NC: The Mint Museum, 2011.

Greene, Carol. Romare Bearden: The Prevalence of Ritual. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1971.

Hanzal, Carla M. Introduction to Romare Bearden: Southern Recollections. Charlotte, NC: The Mint Museum, 2011.

Murray, Albert. Of the Blues: Romare Bearden. Exhibition Catalogue. New York: Cordier & Ekstrom, 1975.

Patton, Sharon. “Collage and Context.” In Romare Bearden & Sheldon Ross, Artist & Dealer. Birmingham, MI: Sheldon Ross Gallery, 2004.

———. “Memory and Metaphor: The Art of Romare Bearden, 1940–1987.” In Memory and Metaphor: The Art of Romare Bearden. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

Pinder, Kimberly N. “Deep Waters: Rebirth, Transcendence, and Abstraction in Romare Bearden’s Passion of Christ.” In Romare Bearden, American Modernist. Edited by Ruth Fine and Jacqueline Francis. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2011.

Profile/Part I: The Twenties. Exhibition Catalogue. New York: Cordier & Ekstrom, 1978.

Profile/Part II: The Thirties. Exhibition Catalogue. New York: Cordier & Ekstrom, 1981.

Rickey, Carrie. “Reviews: New York.” ArtForum 17, no. 6 (1979): 60–63.

Schwartzman, Myron. Romare Bearden: Work with Paper. New York: Baruch College Gallery, 1991.

———. Romare Bearden: His Life and Art. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1990.

Tomkins, Calvin. “Putting Something Over Something Else.” New Yorker 53 (November 28, 1977): 53–77.