Clarence John Laughlin, Staircase Fantasia, 1949, gelatin silver print. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, bequest of the artist, 1985.92.

Despite the widely accepted adage that the camera never lies—it never gives us the truth exactly as the eye sees it. There is always some modification. In the creative photograph the many kinds of modification are so directed and controlled—that the camera gives us, by indirection, interior reality rather than the exterior. And thus, the camera is especially effective in making us realize what a shifting and intricate thing reality is.

—Clarence John Laughlin1

Dear Mr. Stieglitz: I have long wanted to write you. I have continually hesitated and deferred doing so, however, for a number of reasons. One of them was this: I was afraid you were liable to be interested only in those who have done a considerable body of work. For I have not, even now (not in photography at least), and so still feel this hindrance to some extent. Yet, because I now think I comprehend, even at this distance, somewhat better the meaning of what you are and what you have achieved—I have come to conceive it necessary that you see the work I am enclosing—slight in amount though it is, and only fractional of what I hope to accomplish. Even though you should not like the work—I will still believe that I have done what was inevitable.2

These were the first words that Clarence John Laughlin, a twenty-nine-year-old from New Orleans, Louisiana, typed to Alfred Stieglitz—perhaps the most influential figure of American photography in the twentieth century (fig. 1). In his letter of May 20, 1935, Laughlin describes his background, his dislike of the commercial sphere, his endeavors in writing and photography, and his use of the camera as an artistic tool. He lists titles of the prints he has enclosed with his letter, asking Stieglitz to review them and send feedback. Finally, Laughlin writes that he has included “two statements” along with the prints and his letter: “A Statement of Objectives (for a formative group)” and “A Statement of Possible Benefits.”3 Stieglitz wrote back a cordial, yet brief, reply thanking Laughlin for sending the photographs but telling him, “you yourself know most of [the photographs] are as yet not adequate except as ‘ideas.’”4 This was likely a harsh blow to the young Laughlin, who had hoped for recognition in the New York art world and the assurance of an older, distinguished artist that his work was on the right track.

Though Laughlin gives a quick synopsis of what he calls his “psychological background” in the letter to Stieglitz, it is in a later, self-authored chronology of his life that he lists the photographers who shaped him most as a young artist.5 One of these was Stieglitz, unsurprisingly, followed by Paul Strand, Edward Weston, Man Ray, and Eugène Atget.6 Each of these photographers had a particular influence on Laughlin as he developed his own personal vision in photography. From Stieglitz he gleaned an authoritative, directorial voice; from Strand and Weston, the foundations of purist photography, with its careful and deliberate grounding in technique; from Man Ray, alternative and experimental photographic approaches; and from Atget, the development of an eye that sought out the rarely pictured places and things of a bustling city and a love for sculpture, shop windows, and architectural detail.7

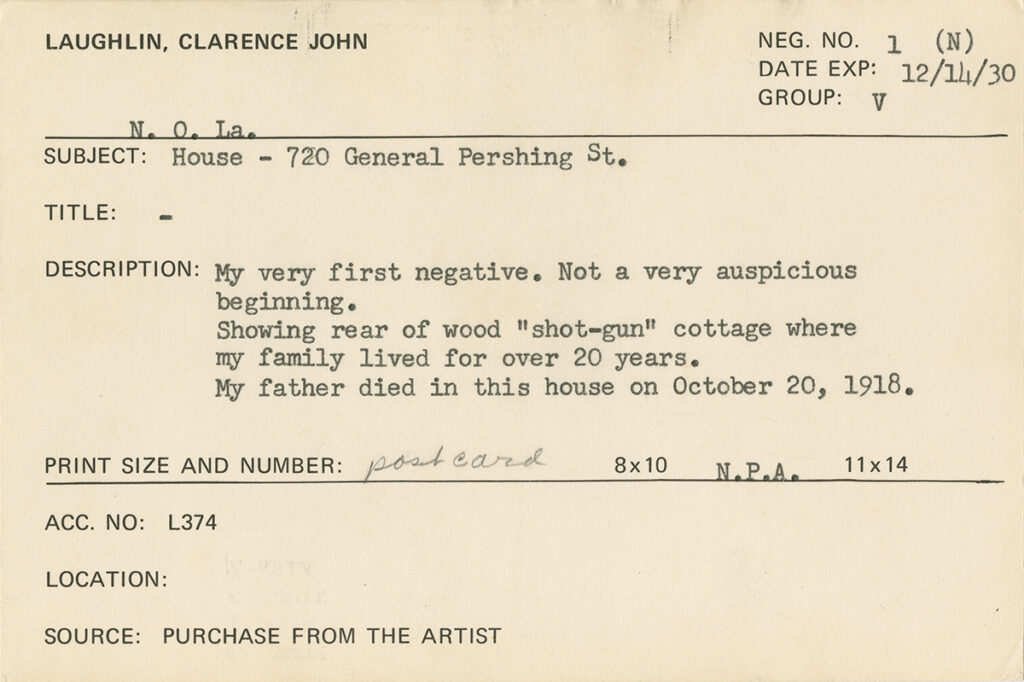

According to the card index system at the Historic New Orleans Collection, where the artist’s papers reside today, Laughlin made his first negative in 1930 (fig. 2).8 On this negative, he exposed an image of his childhood home at 720 General Pershing Street, which runs through the East Riverside neighborhood of New Orleans (fig. 3). In the 1930s, Laughlin had a number of small commercial jobs and for a time also worked as a clerk in a couple of New Orleans banks.9 By 1934, however, he had decided to pursue photography full time and looked for opportunities outside the world of “office creatures,” as he notes in the letter to Stieglitz.10 In 1936, Laughlin landed a job as a Civil Service photographer, working for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and in the fall of 1940 his personal work was exhibited alongside that of Atget at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York.11

-

Fig. 2. Card on which Laughlin recorded the details of his first negative. The Historic New Orleans Collection. Clarence John Laughlin Papers MSS 563, Card Index.

-

Fig. 3. Image from Laughlin’s first negative. Clarence John Laughlin, House, 720 General Pershing Street, 1930, nitrate film negative. The Clarence John Laughlin Archive at The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1983.47.1.1.

Despite this early success, Laughlin encountered many roadblocks along the way as he worked to establish himself as an artist. Stieglitz’s reply to the young photographer in 1935 in some ways foreshadowed the later difficulties that Laughlin would face. He suffered from his isolation in the South, his lack of finances, an incomplete formal education, and an intense personality, which intrigued others as much as it pushed them away. Laughlin had a very strong personal vision, and this led him to be controlling and uncompromising about his work and how it was presented—leading him into arguments with curators, magazine editors, and gallery owners. Later in life, Laughlin would speak about the lack of recognition he had received throughout his artistic career, and this was partly because of his working environment and also because his untempered artistic vision was one that was incredibly multifaceted, making it difficult for critics of his work to put him into a single category.12 This multifaceted vision is reflected by the twenty-three thematic groups into which Laughlin organized his photographs.13

Laughlin drew inspiration not only from the photographic world but also from writers and painters in the United States and abroad. In descriptions, Laughlin always referred to himself as a writer and book collector first and a photographer second.14 His personal library was enormous, consisting of over 15,000 volumes on topics as wide-ranging as art, architecture, fantasy and science fiction, the physical and mental sciences, and antiques (fig. 4).15 The photographer’s father died when he was very young, and he was forced to drop out of school to work and support his family. Laughlin never graduated from high school and never had the opportunity to pursue higher education. Yet his love for literature was sparked at an early age, and whenever Laughlin had spare funds he would invest them in the purchase of a new book for his library. Thus, figures like Charles Baudelaire, Jules Laforgue, and Herman Melville became just as influential in his creative and artistic work as did Stieglitz and Strand.16 These writers occupied a part of Laughlin’s artistic imagination and drove him to explore photography through the poetic concepts of irony and symbolism.

Not a follower of any ordinary, pre-determined path, Laughlin also found inspiration for his photography in the work of twentieth-century Surrealist painters including Max Ernst (fig. 5).17 From Surrealism, Laughlin drew on the importance of the subconscious and the artist’s interior world. Laughlin repeats over and over again in his writings that the photographer should work from the “inside out,” transforming the objects that he photographs into symbols of experience rather than mere records of existence.18 Weeks Hall, a close friend of Laughlin and a fellow Louisiana resident, stated in an article for U.S. Camera, “[Laughlin’s] achievement consists in the fact that these prints are not photographs of these places and these things but are photographed symbols of his thoughts about them.”19 Laughlin articulates his multidimensional approach to photography most clearly in a foundational article he wrote for the College Art Journal in 1957, titled “The Camera’s Methods for Approaching Reality.”20 For anyone looking to understand Laughlin’s work better, this piece is the most precise and condensed account of the photographer’s methods. By 1957, Laughlin was a little over two decades into his career and had developed very clear opinions about his own work, the work of others, and the field of photography as a whole. He stresses that the photographer must approach the object and allow it to affect him “both consciously and subconsciously.”21 Only through an imaginative and interiorized encounter with the object could the photographer penetrate the layers of the ordinary and project a sense of “beyond” into his photographs. Laughlin outlines different methods in which the photographer can work, including traditional approaches, such as documentation and purism, along with a number of less conventional ones, such as the “abstraction of reality,” “transformation of space,” and the “release of the magic of the object.”22 Ultimately, it was Laughlin’s aim to move past a merely naturalistic or formal encounter with the object to one that was more symbolic.23

Statements from the College Art Journal article can be read as an elaboration of views Laughlin expressed in his 1935 introductory letter to Stieglitz. While he explained his ideas about photography to Stieglitz, Laughlin said: “I feel convinced that whole new worlds lie about us, sheathed in what we call ‘commonplaceness’ of reality.…”24 Laughlin thought of photography as a way of seeing beyond the object in front of the camera, of seeing the extraordinary through the ordinary. Commenting on a photograph that he made in 1938, Enigmatic Figure, Laughlin wrote: “This element of the fantastic, contrasted with carefully chosen commonplace surroundings—integrates into an unusual situation in which the extraordinary originates in, and is defined by, the ordinary.”25 For Laughlin, the photographer should not take a close-minded approach but should allow influences from psychology, literature, music, architecture, and other artistic media to shape his work.26 He also embraced experimental photographic techniques and processes as a way of picturing reality in a new and exciting way. Although Laughlin’s approach to photography precluded him from being categorized with any particular group in the twentieth-century American photographic world, it did enable him to produce some of the most original, challenging, and forward-thinking work of his time.

“The Webs of Memory”

The mystery of time, the magic of light, the enigma of reality—and the interrelationships of these problems—are [this photographer’s] constant themes, and preoccupations.

—Clarence John Laughlin27

In his poem “A Point of Age, Part I,” twentieth-century American poet John Berryman reflects on the passage of time and pivotal moments in an individual’s life when one both looks back upon the past and forward to the future.28 Berryman writes, “Images are the mind’s life, and they change. / How to arrange it—what can one afford / When ghosts and goods tether the twitching will / Where it has stood content and would stand still / If time’s map bore the brat of time intact?” These lines suggest that we are constantly re-shaping and re-molding our images, our narratives, and that these must be negotiated not only through daily practicalities but within “time’s map,” which never allows us to remain in one place for very long. Berryman’s verse resonates with a statement that Laughlin made at the height of his photographic career, just nine years after “A Point of Age” appeared in print: “The camera is especially effective in making us realize what a shifting and intricate thing reality is.”29 Both Laughlin and Berryman, in these two examples, indicate that reality is not a fixed entity; it does not simply exist but is constructed and re-constructed over time.

As a photographer, Laughlin was deeply interested in the various ways the camera could approach and construct new realities. In a sheet of study queries that he sent to Indiana University in April 1962, he makes this interest quite clear. Laughlin created the study queries for students at the university to consider while they viewed his photographs.30 To accompany the print The Road to Never Land (1958), Laughlin included a prompt that discusses the concept of escape.31 “Consider,” he says, “that [escape] suggests the possibilities of ‘alternate’ worlds, or ‘alternate’ realities—and makes us ponder the nature of ‘ultimate reality.’”32 For another print, called Bird with a Flowering Head (1937), Laughlin posed a related thought: “Recall that it is only by the completely free play of the imagination—not restricted by rigid logic—that the mind finds new pathways into the mysteries of ourselves, and the world around us.”33 For Laughlin, it was through this freedom of movement that one could discover “alternate realities” and more deeply understand the world. Laughlin believed that this kind of mental agility would give one the tools to arrange and create a new and evolving personal vision. In his writings, he repeatedly uses the term “beyond” to give the idea that the photographer could use his camera to see past the ordinary to the extraordinary, imaginary, and hyper-real.34 Yet Laughlin makes it clear that these imaginative leaps should not pull one away from life but instead toward what he calls a “higher, or more intense [or inclusive], phase of reality.”35

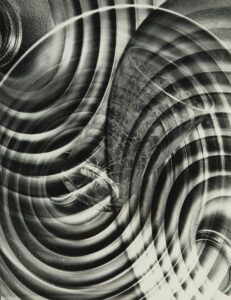

This more intensive relationship to reality is linked, for Laughlin, to a more fluid relationship to time. The construction of reality is always worked out in relation to “time’s map,” to use Berryman’s phrasing. A more extensive understanding of time, one that is not simply focused on the here and now but considers the history of what came before and envisions the possibility of what might follow, was essential to the way Laughlin approached reality through his camera. In Laughlin’s prints, past melds with present and future, yielding a denser and more layered understanding of reality and space. This fluidity between past, present, and future is represented conceptually but also technically, through the use of double exposures. “Double exposure” is the term used to describe how a photographer can expose two separate images onto a single negative, quite literally combining two separate moments in time on the same physical plane. Staircase Fantasia (1949, fig. 6) is an example of double exposure.

Laughlin’s relationship to time was unquestionably influenced by his life in New Orleans, a city that bears its history visibly. In New Orleans, the feeling of déjà vu is ever present, with recurring architectural motifs, block after block of cemetery plots, and the winding Mississippi River, which orients as much as it disorients one’s movement from one neighborhood to the next. Katherine Ware, Curator of Photography at the New Mexico Museum of Art, has written that Laughlin’s photographs are composed in a way that “suggest[s] an atmosphere clouded with layers of history and memories.”36 Ware’s statement not only articulates a significant quality of Laughlin’s work but also captures the character of the environment in which they were produced: the city of New Orleans. In his dedication for New Orleans and Its Living Past, Laughlin says: “And my part I must dedicate to New Orleans, to the secret city which in my photographs I have sought and to the enchantment which is subtly coupled with time past.”37 New Orleans carries with it not only the memories of time past but also the omni- presence of death, decay, and neglect. This macabre aspect of his home city and of the aging South he photographed lent a morbid aspect to Laughlin’s work, representing a struggle to foster life and vitality in an environment of languid motion.

In prints such as The Webs of Memory (1954, fig. 7) or And Tell of Time … Cobwebbed Time (1947, fig. 8), a focus on the past plays an important role in Laughlin’s choice and representation of his subject. In Webs of Memory, a wooden shutter frames a woman’s face and upper body. Cobwebs cover the opening in front of her face, making her appear ghostly, otherworldly. The cobwebs act as a veil to place her at a distance, and their placement—near her hair and around her head—also suggests webs of thought. And Tell of Time … Cobwebbed Time pictures an old clock, also covered in cobwebs, its hands frozen at five past eleven on some day in the distant past.

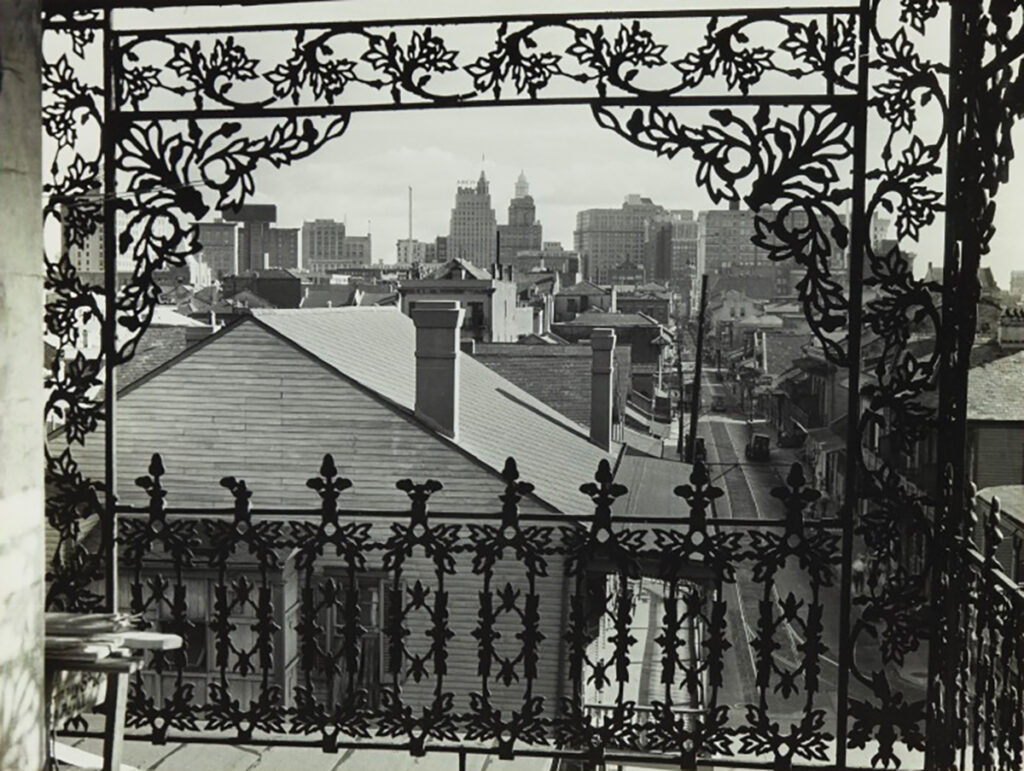

As an artist working in history-laden New Orleans, Laughlin recognized the weight of the past on the individual psyche. However, in his time in the Crescent City, Laughlin also witnessed a great deal of change, as captured in a print from the collection at the New Orleans Museum of Art, The Old and the New (#7) (1938, fig. 9). In this print, one sees the new downtown buildings of New Orleans framed through old, wrought ironwork, demonstrating Laughlin’s interest in the mixture of past and present and his understanding that both can exist on the same plane of reality. By combining elements of old and new New Orleans in a single image, Laughlin suggests that our understanding of the present is always colored by perceptions of and experiences from the past.

-

Fig. 7. Clarence John Laughlin, The Webs of Memory, 1954, gelatin silver print. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, gift of Joshua Mann Pailet in honor of his mother, Charlotte Mann Pailet, her family, and Sir Nicholas Winton, 2016.589.

-

Fig. 8. Clarence John Laughlin, And Tell of Time … Cobwebbed Time, 1947, gelatin silver print. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, gift of Lucinda W. Bunnen for the Bunnen Collection, 1981.80.

-

Fig. 9. Clarence John Laughlin, The Old and the New (#7), 1938, gelatin silver print. New Orleans Museum of Art, Bequest of Clarence John Laughlin, 85.118.136.

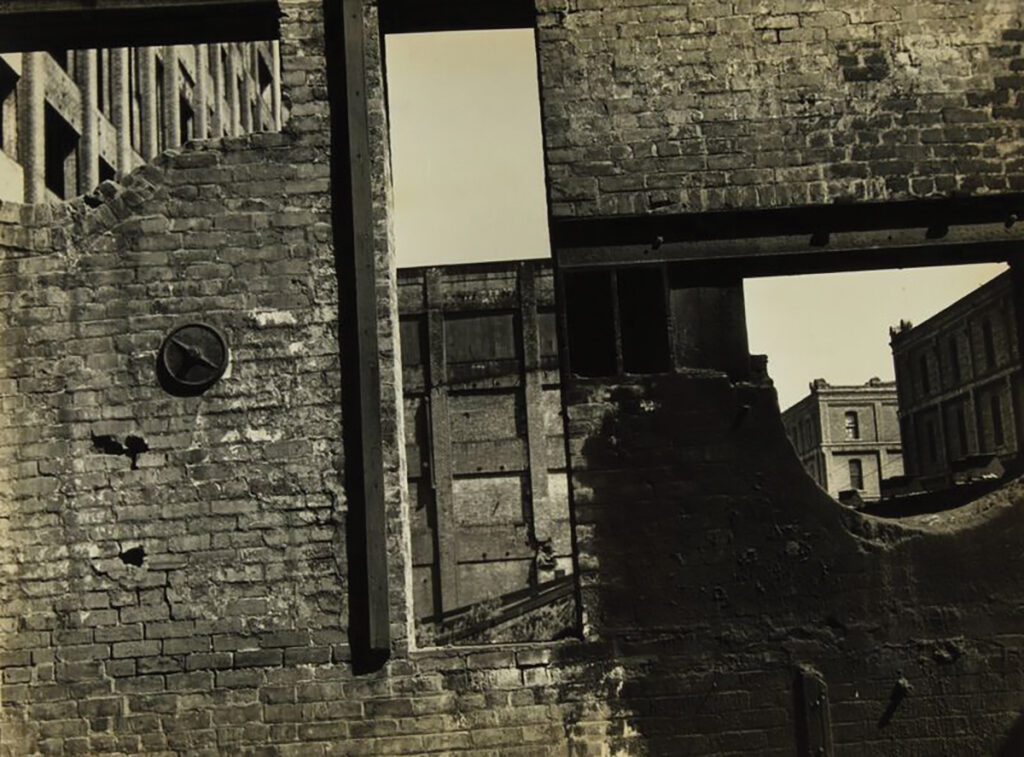

Other prints, such as Entrance to a Sub-World (1954, fig. 10), Construction in Real and Unreal Space (1952, fig. 11), Three Vistas Through One Wall (1948, fig. 12), and Passage [or Road] to Never Land (1958, fig. 13), suggest paths forward into the future.38 At times magical and mystical, these photographs, in one way or another, all present opportunities for alterity. Three Vistas Through One Wall gives three different views—high, middle, and low—through openings in a single brick structure. Each shows a different slice of the city (likely New Orleans); together, they demonstrate that, at any given time, multiple viewpoints—and paths forward—are present. Entrance to a Sub-World pictures an opening in a light-colored wall through which a dark, murky, yet magical scene awaits. In his caption for this print, Laughlin wrote:

-

Fig. 10. Clarence John Laughlin, Entrance to a Sub-World, 1954, gelatin silver print. The Clarence John Laughlin Archive at The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1981.247.1.1358.

-

Fig. 11. Clarence John Laughlin, Construction in Real and Unreal Space, 1952, gelatin silver print. The Clarence John Laughlin Archive at The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1981.247.1.124.

-

Fig. 12. Clarence John Laughlin, Three Vistas Through One Wall, 1948, gelatin silver print. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, gift of Joshua Mann Pailet in honor of his mother, Charlotte Mann Pailet, her family, and Sir Nicholas Winton, 2017.426.

-

Fig. 13. Clarence John Laughlin, Passage [or Road] to Never Land, 1958, gelatin silver print. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, gift of Joshua Mann Pailet in honor of his mother, Charlotte Mann Pailet, her family, and Sir Nicholas Winton, 2017.425.

A small opening in the canvas wall of a homemade trailer is basically what this picture presents. To the eye, it was not only “ugly,” but also so small that most of its inner meaning was imperceptible. But the camera has given it an entirely new meaning by (a) changing its scale so greatly that graphic values, formerly lost, have now become completely visible; (b) by releasing a kind of magic which now makes this small torn orifice like the setting of a sinister stage—an ominous aperture into another kind of world.39

Here, the alternate world or reality is one that is maybe not so pleasant, as Laughlin’s extended comment suggests, but what is important to note is that the camera provides this opportunity for seeing the world in a novel way.

In the prologue to his best-known work on Louisiana plantation architecture, Ghosts Along the Mississippi (1948), Laughlin writes:

The method of poetry is to abstract symbols from the stuff of living experience; to embody these symbols not only in emotive language, but, by means of the creative use of these symbols, to subtly penetrate beyond the tough outer skin of appearances, and give us a reality which is not only complexly sweetened or embittered by the perceiving mind, but more extensive in time, than that reality which is immediately apprehensible; since now elements of the past and of the future play equal parts with that of the present.40

For Laughlin, this is what the camera had the power to do: to allow us to perceive a reality that would be more extensive or expansive in time than the limited understanding of the present. A certain approach to photography could allow one to “penetrate,” as Laughlin says, “the tough outer skin of appearances,” moving past habit and ordinary perception to envision new worlds, new realities, across time and space.

“A Shared Vision”

Laughlin’s use of experimental approaches in photography and his views on picturing alternate realities were shared by photographers including Wynn Bullock and Henry Holmes Smith. With these two photographers—Smith in particular—Laughlin sustained a robust dialogue about photographic theory and practice in the twentieth century. Although Laughlin and Bullock were similarly influenced by the work of the purists of the f/64 group on the West Coast, they each took their work in new directions from this mutual point of origin. Laughlin, Bullock, and Smith all experimented with non-standard photographic techniques, including photograms, solarizations, reticulations, and double exposures. As Laughlin writes in his lecture “The Camera as a Third Eye”: “Not so many people are aware that through montage, through collage, through photograms and solarization, through deliberate and careful double exposure in the camera, and above all, through the symbolic use of the object—the creative photographer can now ‘compose’ as freely as the creative painter.”41 All three photographers worked with color photography at some point in their careers as well. In line with their experimental approaches to photography, Laughlin, Bullock, and Smith created photographic abstractions with new color technology (fig. 14).

-

Fig. 14. Henry Holmes Smith (American, 1909–1986), Royal Pair, 1976, dye transfer print. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, gift of Lucinda W. Bunnen for the Bunnen Collection, 1992.328. © Henry Holmes Smith.

-

Fig. 15. Clarence John Laughlin, The Photographer as Explorer of Space and Light (Wynn Bullock), 1956, gelatin silver print. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase with funds from an anonymous donor in honor of Brett Abbott, 2016.68.

The relationship between Laughlin and California-based photographer Wynn Bullock is wonderfully shown in portraits the two artists made of each other in the 1950s. In Laughlin’s portrait of Bullock, The Photographer as Explorer of Space and Light (Wynn Bullock) (1956, fig. 15), Bullock holds up two pieces of wood that have been joined together at a ninety-degree angle, framing his head. Light from a tall window on the right-hand side of the composition shines onto the floor where Bullock kneels, carving out a form amid the darkness of the room. Laughlin’s portrait highlights Bullock’s interest in the physical and scientific properties of space and light in his photographic work, particularly his fascination with theories of the space-time continuum.42 Laughlin writes in the caption for his portrait of Bullock:

The portrait here is of Wynn Bullock—one of the most sensitive, and individual, of the California photographers—made in his own habitat, so to speak. He kneels near a plane of light that seems to lift itself from the floor; the object held—which defines space and evokes the magic of light—is an intrinsic part of his physical, and mental, surroundings. In a degree—this picture embodies something of his own special feeling for light.43

Likewise, Bullock’s portrait of Laughlin seeks to embody qualities of the Louisiana photographer. In Bullock’s print, Clarence John Laughlin and Edna’s Hand (fig. 16), Laughlin is framed by two windows. We see his shadow and the camera through the front window, while Edna Bullock’s hand wraps mysteriously around a doorway on the left. Bullock’s portrait of his friend is a nod to Laughlin’s frequent use of models’ hands in his compositions and elements of mystery and intrigue in his work, exploring what he called the “enigma of reality.”44 Both photographers were captivated by the magic of light and issues of time and space, attempting to see beyond what is readily perceptible to a world unknown to the naked eye. Bullock wrote that his camera was “not only an extension of the eye, but of the brain.” He added: “It can see sharper, farther, nearer, slower, faster than the eye. It can see by invisible light. It can see in the past, present, and future. Instead of using the camera only to reproduce objects, I want to use it to make what is invisible to the eye, visible.”45 Like Laughlin, Bullock also rejected the merely documentary aspect of photography (“reproduction of objects”) and saw the camera as a tool for charting the map of time (“past, present, and future”). Laughlin’s Language of Light (1952, fig. 17) and Bullock’s Light #1 (1952, fig. 18) demonstrate both photographers’ interest in concepts of light and space.

Henry Holmes Smith and Laughlin began corresponding in 1953 and developed an incredibly close bond. Smith gave the often-tactless Laughlin advice on how to negotiate with museums and educational institutions and encouraged him early on to find a home for his negatives, prints, and papers. The two photographers also had a profound respect for each other’s artistic work and exchanged a number of prints. On one print that Laughlin received from Smith in 1979, he remarked, “I am delighted to get the dye transfer print and the essay. The color image I consider extremely significant—rooted as it is in the rich soil of legend, as well as in your own individual vision.”46 Laughlin placed high value on the “individual vision” of the artist and found Smith’s photographic compositions of light and color to be stimulating, original, and compelling.47 Smith’s essay “An Access of American Sensibility” on Laughlin’s photography was, Laughlin felt, the best-written representation of his work. Laughlin vented to Smith about groups like the Society for Photographic Education (SPE), from which he resigned in 197948 because he felt that the group paid more attention to names and personalities than unique and original work that would push the field ahead.49 He said the same thing of Aperture magazine in a letter to Minor White in 1962, criticizing the magazine for favoring “personalities” over “personal vision.”50 Laughlin, Bullock, and Smith followed a more experimental track in photography than did many of their American counterparts, drawing inspiration from photographic trends that had begun in Europe in the 1920s. Their work originated out of a “new vision” approach—using experimental techniques in photography to see in new ways.51 Laughlin’s work The Abstract and the Ornate (1935, fig. 19) is an example of the trend in photography of exploring the medium’s relationship to light and space.

-

Fig. 17. Clarence John Laughlin, Language of Light, 1952, gelatin silver print. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, gift of Joshua Mann Pailet in honor of his mother, Charlotte Mann Pailet, her family, and Sir Nicholas Winton, 2016.588.

-

Fig. 18. Wynn Bullock, Light #1, ca. 1952, gelatin silver print. Collection of Barbara and Gene Bullock-Wilson. © Bullock Family Photography LLC. All rights reserved

Laughlin maintained correspondence and exchanged prints with a number of other photographers—both in the United States and Europe—throughout his career. Prominent American photographers with whom he corresponded included Man Ray, Paul Strand, Edward Weston, Minor White, and Aaron Siskind. Laughlin kept up an active print exchange with a vast number of photographers as well. Now housed at the New Orleans Museum of Art, Laughlin’s print collection consists of work by figures including Imogen Cunningham, Carlotta Corpron, Ruth Bernhard, Berenice Abbott, Jean Boucher, Brassaï, Ralph Gibson, and Edward Weston. As Laughlin said in a letter to Man Ray on April 1, 1941: “I am more interested in the symbolic use of the camera (which but few photographers have had the imagination to develop) than in its ‘recording’ function—however important that may be.”52 His collection of prints profoundly reflects this belief. Despite Laughlin’s feeling of isolation in New Orleans—away from the busy artistic centers in New York, Chicago, and San Francisco—he was well aware of the photographic work that was being produced throughout the country. In building his own collection of photography, Laughlin did not seek to collect well-established names in photography but instead chose to collect work by photographers—some known, some not—whom he found visually or conceptually compelling. Laughlin shared his vision of “the mystery of time, the magic of light, [and] the enigma of reality” with other photographers of his generation—as well as the generation before and the one after—creating an alternative dialogue around photography in the twentieth century that was not tied to any particular group or channel of thought.

“Legacy of Human Invention”

Laughlin published two major books in his lifetime: New Orleans and Its Living Past (1941) and Ghosts Along the Mississippi (1948). The latter is considered his most successful and was reprinted multiple times during his career. It depicts old Louisiana plantation houses along the Mississippi River. Examples from this body of work include The Enshadowed Pillars (No. 4) (1946, fig. 20), Moss Drapes (1947, fig. 21), and Smoke of Destruction (#1) (1939, fig. 22). On these houses, Laughlin comments: “The best Louisiana plantation houses represent probably the most significant architecture achieved in the entire Mississippi valley during the nineteenth century. They were significant because they were designed in terms of the materials then available, because they did away with all useless ornamentation, and because they were built in terms of the climate and the psychological need of the people of those years.”53 Architecture was a major area of interest for Laughlin, who devoted not only a major book to the subject but also several smaller articles. Laughlin’s essays on architecture include “Simon Rhodia’s Dream Architecture,” “The Faubourgs Marigny and St. Marie,” “The River Houses,” “American Fantastica: Photographs and Commentary,” and “Men and Buildings: American Victoriana.” Louisiana architecture and Victorian architecture were of principal interest to the New Orleans–based photographer. Laughlin was drawn to Victorian architectural works because of their high degree of invention and inclusion of forms molded in unique, individualistic ways. He also admired the work of self-taught architects such as Simon Rhodia, who engineered the Watts Towers in Los Angeles (fig. 23).

-

Fig. 20. Clarence John Laughlin, The Enshadowed Pillars (No. 4) (Chrétian Point Plantation), 1946, gelatin silver print. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, gift of Lucinda W. Bunnen for the Bunnen Collection, 1981.79.

-

Fig. 21. Clarence John Laughlin, Moss Drapes (Evergreen Plantation), 1947, gelatin silver print. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, bequest of the artist, 1985.93.

-

Fig. 22. Clarence John Laughlin, Smoke of Destruction (#1) (Linwood Plantation), 1939, gelatin silver print. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, bequest of the artist, 1985.104.

-

Fig. 23. Clarence John Laughlin, The Incredible Spire: The Watts Towers, 1960, gelatin silver print. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, gift of Jane and Clay Jackson in honor of David A. Brenneman, 2015.161.

In architecture, as in photography, Laughlin believed that it was only through the “completely free play of the imagination” that one could invent new and original designs.54 No rigid logic or structure should be followed, as every climate and every community required a different type of architecture.55 Architecture, Laughlin asserted, “is even more deeply and intricately involved with the lives of people than is furniture—or any of the arts, for that matter.”56 In his essay “American Fantastica: Photographs and Commentary,” Laughlin speaks about architecture as an exterior structure that is concerned with the lives of the people who move about within it. Conversely, the mindset or imaginative capacity of the builder or craftsman affects the form, function, and ornamentation of the structure he builds. From each perspective, the human body remains at the center of the architectural model.57

Laughlin’s vision of the architect reflects his own methods as a photographer, working from the “inside out.”58 He photographed Victorian architecture in San Francisco, Baton Rouge, Galveston, San Antonio, Los Angeles, Sacramento, Chicago, New Orleans, Lake Geneva, and Salt Lake City.59 Above all, Laughlin admired the imaginative capacity of the Victorians, who were constantly inventing new and unusual forms. In “Men and Buildings: American Victoriana,” Laughlin states that the human imagination needs to be surrounded by architecture that bears the mark of “true individuality.”60 Although at times the Victorians over-elaborated their architectural surfaces, Laughlin preferred the vitality and overflow of detail to the stark, deadened, purist structures of modern architecture.61 He felt that modern architects could learn a great deal by looking back to the precedent set by the Victorians.

Many of the photographs Laughlin took of Victorian architecture throughout the United States were the last pictures made of these structures before they were demolished. This was also true for his documentation of Louisiana architecture. From 1949 to 1969, Laughlin supported himself largely by photographing architecture for firms throughout the country.62 Between his personal and commercial photographs of architecture, he left an enormous legacy of architectural photography. Laughlin’s photographs of the South built on the photographic record of Southern plantation architecture. His photographs of Belle Grove, Bocage, and Afton Villa can be compared to the work of Walker Evans, who photographed many of the same structures. Both photographers shared a love for architecture yet represented the Southern plantations in very different ways. Laughlin’s photographs stress the atmosphere of place while Evans’ pictures focus on form. The High Museum’s collection of Laughlin photographs is significant in that it has prints of over a dozen Louisiana plantations: unique documents of antebellum Southern architecture.

Conclusion

For Clarence John Laughlin, the camera could be used as a tool to imagine new planes of reality and new possibilities of existence. He never accepted any single dogma or affiliated himself with any particular brand of photography, recognizing that his fluid approach to the world would allow him to convey his personal vision much more clearly. In “A Statement on Photography,” which the photographer wrote in 1979, six years before his death, he said:

To me, photography is an activity by which we can discover our own creative potentials—by means of a medium whose nature is peculiarly suited to our own time. Since it is so commonly, and widely, used, it can help us to discover, in a world filled with ugliness and violence, some of the magic and mystery hidden from us behind the things whose nature, and meaning, we only think we know. And above all, it is a means that can help us preserve, and enhance, our own humanity—amid a society which is growing increasingly anti-human.63

Laughlin resisted the idea that the camera was simply a mechanical tool, often saying that the camera is “only a machine when used mechanically.”64 He insisted on a deeper relationship to experience, one embedded with poetry and symbolism. Just as the poet constructs symbols of experience through his words, so too does the photographer make choices about how his images construct and transform reality. And, importantly, the work of the poet or photographer does not lead away from reality but creates a richer, more human understanding of the world around us.

Sifting through the many folders and boxes that comprise Laughlin’s archive at the Historic New Orleans Collection, one might come across a small sheet of paper, around 3 x 5 inches, the last document in its folder. A short note is scribbled in Laughlin’s handwriting, with the brief title “Taken + made.” Laughlin explains:

No creative photo is “taken”—that implies an entirely passive role by the photographer. A “creative” photo is “made.” It is “made” by an act of imagination on the part of the creative photographer. An act by which he “displaces” (or transcends) the “common” place or “public” meaning of the object—by a new meaning he himself perceives—and by which he presents the individualized meaning he himself has “discovered”—for the edification and revelation to the viewer.65

This note is modest in length, but it says everything about Laughlin: his ideas about the role of the imagination, the interior world of the artist, and the power of the camera to transcend the common and reach the symbolic.

Laughlin’s radical ideas about photography and his location in New Orleans kept him from more widespread recognition in the United States. In a 1955 letter, he laments:

Since I must work down here in almost complete isolation—with no co-workers, no colleagues, no disciples, with almost total indifference all around me— and since I have never been a member of any sort of group (such as exists on the West Coast)—and since my work, because of its range, and bulk, does not fit easily into any of the recognized categories—it naturally follows that I am written about but very rarely—and practically never interviewed. And, of course, no one ever mentions my work in connection with the top “recognized” photographers.…66

Minor White and other critics encouraged Laughlin to pare down and streamline his work, but Laughlin refused to compromise his vision or change his working method.67 Looking back, what is most admirable about Laughlin’s work is that he took risks and experimented with compositions and techniques that were not common during his time. Sometimes this led to obscure or unimpressive work, but sometimes—as John Lawrence points out with the Poems of the Interior World series—it resulted in work that was quite challenging and provocative.68 Laughlin created new visual realities and contributed to the dialogue on twentieth-century society through his art. His work gives a unique perspective on life in America during the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s, serving as an alternative vision to that offered by the dominant forces in photography of the period.

Laughlin’s approach also created a third path for photographers of later generations, such as Ralph Eugene Meatyard and Ralph Gibson, to follow. In a late interview recorded with Patricia Leighton in 1979, Laughlin said: “The creation of the work of art should set free in you the things which you cannot set free [in] any other way. That’s its fundamental purpose; it’s got to do this for you. And if it can do this for you, then maybe it can affect other people.”69 Out of his turbulent past, Laughlin created work of beauty and complexity, inspiring a new generation of photographers to remain true to their own personal visions, to keep their minds open to influences from other fields, and to realize that reality is as malleable as one’s approach to the camera.

—Catherine Barth, Emory University, Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship, High Museum of Art Photography Department, 2016

Selected Bibliography

Abbott, Brett, Barbara Bullock-Wilson, and Maria Kelly. Wynn Bullock: Revelations. Atlanta: High Museum of Art, 2014.

Berryman, John. The Heart Is Strange: New Selected Poems. Ed. Daniel Swift. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2014.

Bullock, Wynn. “Space and Time.” In Photographers on Photography: A Critical Anthology. Ed. Lyons, Nathan. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall Inc., 1966.

Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona. Clarence John Laughlin. Tucson, AZ: Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona, 1979.

Davis, Keith F. “A Forest of Symbols: The Early Work of Clarence John Laughlin.” In Clarence John Laughlin: Visionary Photographer, 9–21.

———. “Laughlin’s Photographic Groups.” In Clarence John Laughlin: Visionary Photographer, 152–155.

Davis, Keith F., Nancy Barrett, and John H. Lawrence. Clarence John Laughlin: Visionary Photographer. Kansas City, MO: Hallmark Cards, 1990.

Laughlin, Clarence John. “The Camera’s Methods of Approaching Reality.” College Art Journal 16 (1957): 297–306.

———. Ghosts Along the Mississippi: An Essay in the Poetic Interpretation of Louisiana’s Plantation Architecture. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1948.

———. Ghosts Along the Mississippi. New York: American Legacy Press, 1987.

———. “Men and Buildings: American Victoriana.” Perspecta 17 (1980): 80–91.

Laughlin, Clarence John, David L. Cohn, and Bruce Rogers. New Orleans and Its Living Past. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1941.

Laughlin, Clarence John, Papers. THNOC MSS 563, Box 71, Folder 18. The Historic New Orleans Collection, New Orleans, LA.

Lawrence, John H. “Clarence John Laughlin’s Poems of the Interior World: A Philosophy in Photographs.” In Clarence John Laughlin: Visionary Photographer, 23–33.

Leighten, Patricia. “Clarence John Laughlin: The Art and Thought of an American Surrealist.” History of Photography 12 (2013): 129–146.

Lemagny, Jean-Claude. Atget the Pioneer. New York: Prestel, 2000.

Moholy-Nagy, László. “American Fantastica: Photographs and Commentary.” The Saturday Book 26 (1966): 48–67.

———. The New Vision (New York: Wittenborn, Schultz, Inc.), 1949.

Philadelphia Museum of Art Press Release. “Clarence John Laughlin’s Poetic Photographs of New Orleans’ Architecture on View in Exhibition,” December 3, 2005. http://www.philamuseum.org/press/releases/2005.html.

Stieglitz, Alfred, Correspondence. Alfred Stieglitz/Georgia O’Keeffe Archive. YCAL MSS 85, Box 30 of 700. Yale Collection of American Literature. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Yale University.