Fig. 1. Guercino (Giovanni Francesco Barbieri) (Italian, 1591–1666), Christ and the Samaritan Woman, ca. 1650, oil on canvas. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, gift of Julie and Arthur Montgomery, 1980.56.

A long-ignored painting of Christ and the Samaritan Woman (fig. 1) by Giovanni Battista Barbieri, known as Guercino (1591–1666), in the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, provides an opportunity to reconsider the Baroque painter’s creative process. The High’s painting is one of a group of five canvases in which Guercino and/or his workshop visited the theme of Christ and the Samaritan Woman. The earliest of these, which was executed in the 1620s (fig. 2), has elicited positive attention in modern scholarship for its exuberant brushwork and so-called Caravaggesque style.1 However, the later versions (figs. 3, 4, 5) have elicited less than enthusiastic responses.2 Dating to the 1640s, they are generally characterized as careful, austere, classicizing, and easily imitated. The High’s painting, which belongs to the latter group, was branded as a copy of the painting now owned by the Banco Popolare of Modena (fig. 5) when it entered the High’s collection in 1981 and remained in obscurity until recently.3

-

Fig. 2. Guercino (Giovanni Francesco Barbieri) (Italian, 1591–1666), Christ and the Woman of Samaria, ca. 1619–20, oil on canvas. Kimbell Art Museum, Ft. Worth, acquired in 2010 in memory of Edmund P. Pillsbury, director of the Kimbell Art Museum, 1980–1988. Photo: Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas/Art Resource, NY.

-

Fig. 3. Guercino (Giovanni Francesco Barbieri) (Italian, 1591–1666), Christ and the Woman of Samaria at the Well, ca. 1640–41, oil on canvas. Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, inv. no. 176 (1976.55). Photo © Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid.

-

Fig. 4. Guercino (Giovanni Francesco Barbieri) (Italian, 1591–1666), Christ and the Samaritan Woman, 1640–41, oil on canvas. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, purchased 1965, 14809.

-

Fig. 5. Guercino (Giovanni Francesco Barbieri) (Italian, 1591–1666), Christ and the Samaritan Woman, 1647, oil on canvas. Collezione Banco BPM, Modena, BSG-441. © Archivio Fotografico Banco BPM.

The main reason why the High’s painting was deemed to be a copy of the version now owned by the Modena bank relates to a larger problem that has plagued Guercino studies, namely, the painter’s pervasive reuse of motifs and figures. Guercino’s imitative practice has given rise to the modern perception that the painter lacked the creative genius of his contemporary and rival, “the divine” Guido Reni (1575–1642).4 Additionally, Guercino’s cost-per-figure pricing structure recorded in the painter’s Libro dei Conti, or account book, has been construed as a mechanical approach to painting that privileged cost over innovation.5 Instead of accepting the value-laden distinctions of an original and a copy on their own terms, this paper will shift the basis of discussion to fresh ground and consider what Guercino’s use of drawings reveals about the creative processes that produced the High’s painting and its variants. In the process, it will also begin to evaluate what copying might mean in the context of a group of works that creatively piece together material from a variety of sources. The scandal generated when artist Giovanni Lanfranco accused Domenichino of theft in his “copy” of a painting by Agostino Carracci demonstrates that the line between imitation and innovation was recognized and debated in the seventeenth century.6 Studies of Guercino, though, have not adequately situated the self-taught painter within this broader socio-historical context. From a modern perspective, it is by no means easy to draw a line between a derivative copy and an inventive one in a group of works like the four paintings of Christ and the Samaritan Woman produced by Guercino and his workshop in the 1640s.

With this problem in mind, I will begin with a close analysis of the relationship between the High’s painting (see fig. 1), a supposed workshop copy, and its model (see fig. 5), the presumed authentic version.7 There are many similarities between the two works. Except for the mirror reversal of the well and tree, the compositional frameworks of the two paintings are close. The brass water pail, the well implements, and the indentations on the well appear almost identical in both versions. Yet there are also many differences, ranging from the positioning of the figures to the background edifices. The most immediate and telling difference between the two canvases is in the gestures of the two Christ figures. Christ’s gesture in the High’s canvas was previously explained as an insignificant variation presumably created by one of Guercino’s workshop protégés.8 In fact, the gestures in the two paintings appear to have been carefully chosen to convey discrete facets of the biblical story depicted. The Gospel of John 4:1–42 records that Christ successfully converts the Samaritan Woman to Christianity following a metaphysical discussion of the spiritual versus the physical properties of water.9 In the Modena version, Christ places one hand on his chest and points with his other to the woman’s water vessel, suggesting the attainability of spiritual salvation so long as the woman pledges her faith to Christ. Guercino underscores the theme of salvation by placing a barren tree reminiscent of a cross on the horizon to the left of Christ. In the High’s canvas, this tree is noticeably absent, and Christ in turn presses his left thumb into the pointer figure of his right hand. This well-known rhetorical gesture denotes teaching, and its inclusion in conjunction with a scene of Christ and the Samaritan Woman intimates the importance of spreading Christianity in Counter Reformation Italy.10

Preparatory drawings for the High’s painting will prove useful in elucidating the artistic process that gave rise to such variations on a theme. But before moving to a consideration of specific cases, it is important to recognize the special importance that the predominantly self-taught Guercino placed on drawing.11 In Disegno e Colore, or Drawing and Coloring (fig. 6), ca. 1640, Guercino personified the two essential elements of the artistic process as male and female. An elderly, bearded Disegno, wearing colors reminiscent of red chalk, black ink, and white heightening commonly used in drawing, tenderly presents a small drawing of a sleeping putto to his seated female companion, Colore. With her brushes and palette in hand, Colore gazes over her shoulder, intently scrutinizing the contours of the drawing before her. The image on Colore’s canvas confirms that she is indeed copying the sleeping putto and, in a sense, literally endowing the drawn image with brilliant colors and chiaroscuro effects. Unlike his Bolognese contemporaries, who generally saw disegno and colore as deeply co-involved, as they appear to be in Guido Reni’s painting of the same subject (fig. 7), Guercino saw a hierarchical relation between them. His painting of Disegno e Colore suggests drawing’s foundational and didactic role.

-

Fig. 6. Guercino (Giovanni Francesco Barbieri) (Italian, 1591–1666), Disegno e Colore (Drawing and Color), ca. 1640, oil on canvas; Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, 369. Photo by Asmus Steuerlein.

-

Fig. 7. Guido Reni (Italian, 1575–1642), Alliance between Disegno and Colore, ca. 1620–25, oil on canvas. Musée du Louvre, Inv. 534.

In actual practice, the relation between drawing and coloring in Guercino’s works is far from fixed. Underdrawing and pentimenti visible in the High’s painting show that Guercino made constant modifications in the practice of coloring (figs. 8, 9, 10). Comprehensive examinations of his body of graphic work confirm that the painter rarely executed presentation drawings. Rather than prefiguring an entire composition in a drawing, he made studies of isolated figures or gestures.12 Two surviving drawings that relate respectively to the figures of Christ and the Samaritan Woman in the High’s canvas (figs. 11, 12) typify the rapid, disjointed studies Guercino favored. After completing such studies, Guercino then cultivated the most successful elements to transfer to canvas—but as the drawings for the High’s painting show, he did not translate them exactly. Minor adjustments could have profound implications for how his images were interpreted.

-

Fig. 8. Christ and the Samaritan Woman, ca. 1650 (detail). High Museum of Art.

-

Fig. 9. Christ and the Samaritan Woman, ca. 1650 (detail). High Museum of Art.

-

Fig. 10. Christ and the Samaritan Woman, ca. 1650 (detail). High Museum of Art.

-

Fig. 11. Guercino (Giovanni Francesco Barbieri) (Italian, 1591–1666), Study for Christ and the Samaritan Woman, 1648, pen and brown and brownish-grey wash. Royal Collection, Windsor Castle, RCIN 902791. Photo: Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019.

-

Fig. 12. Guercino (Giovanni Francesco Barbieri) (Italian, 1591–1666), Profile Study of the Samaritan Woman, mid-1630s, pen and brown ink and wash over black chalk. Private collection. Photo courtesy Sotheby’s, New York.

If Guercino did not simply replicate his drawings on canvas or color in a set of contours, how then might we understand the priority given to drawing in his thought and practice? One answer to this question may be deduced from the artist’s personal collection, which by the 1650s comprised some several thousand drawings by the artist’s own hand.13 Letters reveal that Guercino received offers from patrons to purchase his drawings, but the painter refused. In one such letter, Guercino defended his position by claiming that he required his drawing collection intact as a source of reference for the creation of new compositions.14 This extraordinary claim, combined with documentary evidence suggesting that Guercino organized his drawings by subject matter, indicates that the artist utilized his drawing collection as a type of image repertory. Furthermore, recent scholarship has established that paintings executed late in Guercino’s career were created with the aid of drawings completed decades prior.15

Complementing his own drawings, Guercino, at the time of his death, owned an additional five hundred framed and countless other loose engravings and drawings by artists he admired, including da Vinci, Titian, Correggio, and Raphael. A print from his collection proves relevant for the discussion of the High’s painting: an engraving of Annibale Carracci’s (1560–1609) painting Christ and the Samaritan Woman (fig. 13).16 While Annibale executed several versions of this narrative over the course of his career, his painting of 1604–1605 is the only prior painted instance I have found of the teaching gesture in conjunction with this biblical scene. The similarities between Christ in Annibale’s work and Guercino’s preparatory drawing (see fig. 11) are indeed striking and suggest that Guercino looked to his Bolognese predecessor for inspiration.

Guercino’s reliance on the graphic arts for the formation of his paintings can be traced back to his earliest documented work. In Carlo Cesare Malvasia’s Felsina pittrice: vite de pittori bolognesi published in 1678, the biographer chronicled the lives of painters working in Bologna including Guercino. Malvasia knew the painter personally and recounted that Guercino’s first artistic endeavor was copying an engraving of the Madonna della Ghiara or the Madonna di Reggio on the façade of his parents’ house.17 Guercino’s painting unfortunately does not survive, but this formative experience established the painter’s lifelong relationship with prints.

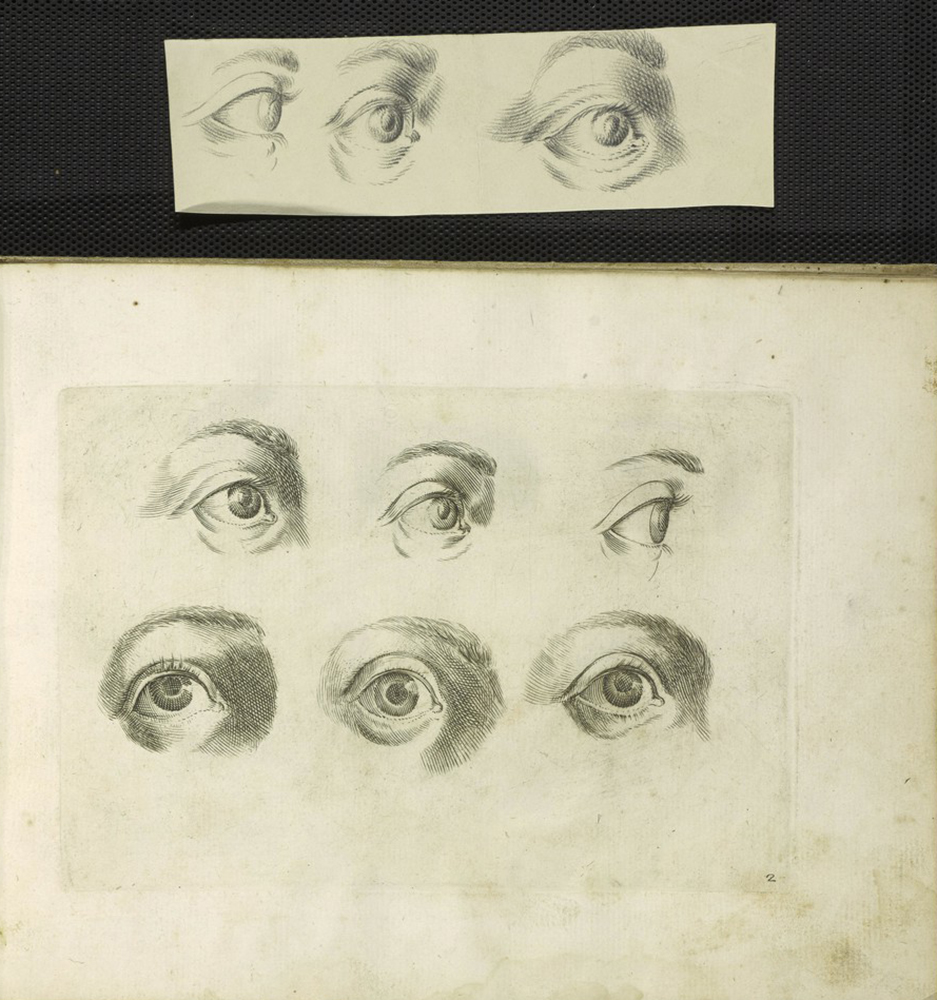

In 1619, Guercino produced a printed drawing book that provides greater insight into his approach to image making. The manual was designed to teach aspiring artists the art of disegno, and it contains twenty-two engravings after original drawings by Guercino.18 These illustrations provide a variety of useful subjects for an artist-in-training, such as foreshortened studies of heads in profile, hands, feet, light effects, and twisted torsos (figs. 14, 15, 16, 17).19 Each engraving is essentially a deconstructed study of crucial components for the creation of a figural composition. The manual’s aim was to encourage the imitation of forms and figures to enable a beginning artist to ultimately develop his own style, as evidenced in a copy of the printed drawing book now at Rose Library in which a later owner has painstakingly copied the eyes from plate 2 (see fig. 17). The drawing book proved to be excessively popular and was reprinted numerous times in Italy, France, and England over the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.20

-

Fig. 14. Oliviero Gatti (Italian, 1568–1651), engravings after Guercino, plates 7, 10, 13, and 2 in Studies from Initial Elements to Introduce the Young to Drawing, 1619–1620, reprinted by Gian Giacomo de Rossi after 1648. Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University.

-

Fig. 15. Oliviero Gatti (Italian, 1568–1651), engravings after Guercino, plates 7, 10, 13, and 2 in Studies from Initial Elements to Introduce the Young to Drawing, 1619–1620, reprinted by Gian Giacomo de Rossi after 1648. Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University.

-

Fig. 16. Oliviero Gatti (Italian, 1568–1651), engravings after Guercino, plates 7, 10, 13, and 2 in Studies from Initial Elements to Introduce the Young to Drawing, 1619–1620, reprinted by Gian Giacomo de Rossi after 1648. Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University.

-

Fig. 17. Oliviero Gatti (Italian, 1568–1651), engravings after Guercino, plates 7, 10, 13, and 2 in Studies from Initial Elements to Introduce the Young to Drawing, 1619–1620, reprinted by Gian Giacomo de Rossi after 1648. Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University.

Thinking about Guercino’s individual paintings as summations and re-articulations of the parts assembled in his own collection of drawings and engravings sheds light not only on his own imitative practice but also on the practices by means of which his contemporaries would have evaluated his paintings. Guercino’s ideas on imitation were not idiosyncratic but rather were part of a larger conversation about copying that was occurring in seventeenth-century Italy. According to the Grande dizionario della lingua italiana, one of the seventeenth-century senses of the word “copy,” or copia, meant abundance or plenitude but not necessarily the complete replication of an entity.21 The ancient Roman rhetorician Quintilian, whose writings underwent a resurgence in the seventeenth century, wrote at length about the quandary of copying in his Institutio Oratoria.22 In this text, Quintilian initially cautions against direct imitation, asserting the inferiority of a reproduction in relation to its original. However, he later modifies his stance when characterizing the perfect orator. He asserts:

If we have thoroughly appreciated all those points, we shall be able to imitate our models with accuracy. But the man to these good qualities adds his own, that is to say, who makes good deficiencies and cuts down whatever is redundant, will be the perfect orator of our search … for this glory also shall be theirs, that men shall say of them that while they surpassed their predecessors they also taught those who came after.23

It remains unclear if Guercino ever read Quintilian, yet the author’s ideas on copying elucidate aspects of Guercino’s practice. As Quintilian instructed aspiring orators, Guercino, too, carefully studied aspects of successful works and other painters’ styles in order to emulate and reformulate them into innovative canvases.

This same rhetorical model can be adapted to think about the reception of Guercino’s paintings by his contemporaries. The literature on seventeenth-century viewing practices reveals that Italian viewers were primed to analyze disparate elements of a painting in order to envision its whole.24 Guercino’s collecting practices mirrored those of his elite patrons, who amassed expansive collections of paintings, prints, drawings, and the decorative arts and cultivated the ability to form and identify visual associations across media. What previous scholars have labeled mechanical repetition in Guercino’s corpus, as evidenced by the High’s painting of Christ and the Samaritan Woman, needs to be considered in this new light, where innovation is the product of active associative understanding. Through the re-formation of a recognizable repertory in the High’s canvas, Guercino re-invented biblical narrative in a manner that emphasized the importance of preaching and conversion to the post-Tridentine Catholic church.

—Kimberly Schrimsher, Emory University, Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Graduate Fellowship Program in Object-Centered Curatorial Research, 2016

Selected Bibliography

Brooks, Julian, and Nathaniel E. Silver, eds. Guercino: Mind to Paper. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2006.

Cazort, Mimi, et al. Guercino, Master Draftsman: Works from North American Collections. Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada, 1991.

Cropper, Elizabeth. The Domenichino Affair: Novelty, Imitation, and Theft in Seventeenth-Century Rome. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005.

Dempsey, Charles. “The Carracci Reform of Painting,” in The Age of Correggio and the Carracci: Emilian Painting of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. Washington, D.C.: The National Gallery of Art, 1986.

Fried, Michael. After Caravaggio. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016.

Ghelfi, Barbara, and Denis Mahon. Il Libro dei Conti del Guercino: 1629–1666. Bologna: Njova Alfa, 1997.

Gozzi, Fausto, et al. Guercino: The Triumph of the Baroque. Warsaw: The National Museum in Warsaw, 2013.

Hassall, Douglas. “Quintilian and the Public Attainment of Justice,” in Rediscovering Rhetoric: Law, Language, and the Practice of Persuasion. Ed. Justin T. Fleeson and Ruth C. A. Higgins. Sydney: The Federation Press, 2008.

Loh, Maria H. “New and Improved: Repetition as Originality in Italian Baroque Practice and Theory.” Art Bulletin (2004): 477–504.

Mahon, Denis, ed. Guercino: Master Painter of the Baroque, 1591–1666. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1992.

Malvasia, Carlo Cesare, et al. Felsina pittrice: Lives of the Bolognese painters. London: Harvey Miller Publishers, 2012.

Negro, Emilio, and Nicosetta Roio. L’eredità del Guercino: l’inventario legale di Giovan Francesco e Filippo Antonio Gennari. Modena: Artioli Editore, 2007.

Quintilian. The Institutio Oratoria of Quintilian in Four Volumes. Vol. 2. Trans. H. E. Butler. London, William Heinemann, 1922.

Salerno, Luigi. I Dipinti del Guercino. Rome: Ugo Bozzi Editore, 1988.

Spear, Richard E. The “Divine” Guido: Religion, Sex, Money, and Art in the World of Guido Reni. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997.

———. “Guercino’s ‘Prix-Fixe’: Observations on Studio Practices and Art Marketing in Emilia.” Burlington Magazine 136 (1994): 592–602.

Stone, David M. Guercino, Master Draftsman: Works from North American Collections. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Art Museums, 1991.

Turner, Nicholas. The Paintings of Guercino: A Revised and Expanded Catalogue Raisonné. Rome: Ugo Bozzi, 2017.

Turner, Nicholas, and Carol Plazzotta. Drawings by Guercino from British Collections. London, British Museum Press, 1991.

Zafran, Eric M. European Art in the High Museum. Atlanta: High Museum of Art, 1984.