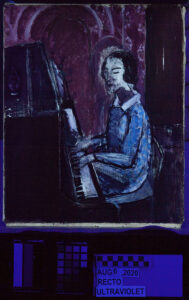

Fig. 1. Henri Matisse (French, 1869–1954), Woman Seated at Her Piano (Femme assise devant son piano), ca. 1924, oil on canvas, 18 1/4 x 15 1/8 inches, High Museum of Art, Atlanta, Doris and Shouky Shaheen Collection, 2019.149. © 2023 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

A quick glance at Henri Matisse’s Woman Seated at Her Piano (fig. 1) at the High Museum of Art reveals what appears to be an “unfinished” painting. As the title suggests, a woman sits at the center of the composition, turned to the left and seemingly engrossed in her piano playing. Yet she is sketchily rendered, her hands barely more than a muddy smudge of paint scraped across the keys, which themselves are lost in a thin wash of white smeared with the blue of the woman’s dress and the brown and black of the surrounding piano. Perhaps most striking is the faint halo tracing the woman’s silhouette, hinting at the ghost of an earlier rendering positioned slightly closer to the piano in the center of the canvas, which is also indicated by the shadow of a previously sketched elbow and forearm hovering just below the woman’s left arm. Interestingly, however, Matisse has boldly signed the work with black paint in the bottom left corner, an act that not only claims the work as his own but one that also signifies completion.

The High’s painting is often considered a study for Matisse’s more complex piano paintings from the same period, such as The Piano Lesson (fig. 2), included in the private collection of David and Ezra Nahmad, or Pianist and Checker Players (fig. 3) at the National Gallery of Art, as well as Little Pianist, Blue Dress (Musée Matisse, fig. 4), and Pianist and Still Life (Kunstmuseum, Bern; fig. 5). But rather than relegating it to the level of a preparatory work, my study aims to examine the High’s painting through an analysis of Matisse’s working methods, his interest in working serially, and his continual play with varying modes of representing the natural world. While at first the topic of these paintings might seem to be convivial scenes of parlor music, the series takes the act of painting as its main subject, picturing the process by which the world is made over into art and form as well as the intrinsic tension that results.

-

Fig. 2. Henri Matisse (French, 1869–1954), La Leçon de piano (The Piano Lesson), 1923, oil on canvas, 25 5/8 by 31 7/8 inches. © 2023 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Archives Matisse, all rights reserved.

-

Fig. 3. Henri Matisse (French, 1869–1954), Pianist and Checker Players, 1924, oil on canvas, 29 x 36 3/8 inches, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, 1985.64.25. © 2023 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

-

Fig. 4. Henri Matisse (French, 1869–1954), Little Pianist, Blue Dress (Petite Pianiste, robe bleue), 1924, oil on canvas, Musée Matisse, Nice, France, bequest of Madame Henri Matisse, 63.2.18. © 2023 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: François Fernandez.

-

Fig. 5. Henri Matisse (French, 1869–1954), Piano Player and Still Life, 1924, oil on canvas, Kunstmuseum, Bern, Switzerland. © 2023 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Archives Henri Matisse.

Producing a series of paintings focused on the same subject was nothing new for Matisse. In fact, a quick glance at his oeuvre reveals the artist’s interest in representing the same subject over again, albeit through vastly different means. For instance, the High’s painting and its related series do not mark the first attempts Matisse made to take on the piano, as can be seen in his two piano paintings from 1916 and 1917. The austere level of reduction and abstraction in The Piano Lesson of 1916 (fig. 6) resembles that in others of Matisse’s paintings of this time, such as Bathers by a River (1909–1917), in which Matisse’s son Pierre sits behind a piano in the bottom right corner.1 One can make out easily enough the blue book of music leaning against the black, scrolled music stand, a candle and pyramidal metronome sitting just in front on the piano’s red top, and what seems to be a sculpture of a nude woman in the bottom left corner.2

An open window appears directly behind the boy, its black metal railing mimicking the curled design of the music stand. Yet beyond this, detail is lost. While the foreground is moderately legible, the background is emptied, subsumed into a flat gray that seems to bleed from the interior wall of the room to outside of the window, cut off only by a sharp diagonal of bright green, which is the lone hint of nature or an exterior world. A similar diagonal cuts into the left side of the boy’s face, whose left eye and forehead disappear into two flat rectangles of gray and peach.

Taking the same subject and painted as a pendant to The Piano Lesson, The Music Lesson of 1917 (fig. 7) also depicts Pierre seated at the same piano, this time occupying the lower left corner of the room, with the open window just behind overlooking a lush, green garden. The similarities stop there for the most part, though, as the 1917 painting overflows with detail in comparison. Matisse’s daughter, Marguerite, sits at the piano next to her brother, with their other brother, Jean, in the chair beside them, a cigarette hanging from his mustachioed mouth and his gaze turned down toward the book in his hands. Outside the window, Matisse’s wife, Amélie, reclines with her needlework before a small pool and sculpture in the background.3 Looking at these two paintings made just a year apart, one can note Matisse’s interest in depicting a similar subject in vastly different ways. Yet what remains odd in this example—at least compared to the popular trajectory of modern art that supports a gradual transition from naturalistic to abstract, or figurative to nonfigurative—is that the more naturalistic painting comes after the more abstract one.

-

Fig. 6. Henri Matisse (French, 1869–1954), The Piano Lesson, Issy-les-Moulineaux, late summer 1916, oil on canvas, 95 1/2 x 83 3/4 inches, Museum of Modern Art, New York, Mrs. Simon Guggenheim Fund, 125.1946. © 2023 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY.

-

Fig. 7. Henri Matisse (French, 1869–1954), The Music Lesson, 1917, oil on canvas, 96 x 78 3/4 inches, The Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, BF717. © 2023 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo © The Barnes Foundation/Bridgeman Images.

While many considered this shift in Matisse’s style a downgrade—criticizing his Nice paintings of the 1920s for their “decadence” of saturated color, pattern, and detail compared to his work of the previous decades4—the artist thought nothing of the sort, rather regarding this turn as further exploration into the subject at hand. In his 1908 “Notes of a Painter,” Matisse discusses how his work isn’t necessarily wedded to one style or look over another despite aiming toward a similar outcome: “My destination is always the same, but I work out a different route to get there.”5 Reflecting on this transitional period in his work, Matisse stated, “when you’ve exploited the possibilities inherent in a certain direction, eventually you have to turn around and seek something new.… One must always keep one’s freshness of vision and of emotion; one must follow one’s instincts. Besides, I’m seeking a new synthesis.”6

For Matisse, it all came down to what he considered was a search for the “essential character” of his subject, which could usually only be captured through a process of reworking and refining, ultimately culminating in a “state of condensation of sensations which constitutes a picture,” or a state of completion.7 “When the synthesis is immediate,” Matisse wrote, meaning realized too soon, “it is premature, without density, and the impoverished expression comes to an insignificant conclusion, ephemeral and momentary.”8 Reaching this condensed or completed state for Matisse meant working on his subject repeatedly through multiple iterations, documenting his “sensations” by means of working serially, often even fluctuating between different styles of representation along the spectrum between naturalistic and abstract.

But beyond this notion of series, Matisse even played with multiple modes of representation within the same work, not restricting himself to one stylistic choice or outcome over another. Take Portrait of Olga Merson, 1911 (fig. 8), for example. What appears at first glance as a traditional portrait is anything but: a woman sits primly on top of a deep blue surface, her hands folded in her lap, staring directly out at the viewer—yet her body is marked by a thick, black line that cuts from her chin to her left thigh, while the left side of her face seems almost blurred as if in motion. Just as in the High’s Woman Seated at Her Piano, Matisse’s Portrait of Olga Merson has the same smudged, re-worked appearance, complete with the ghost of earlier renderings around the subject’s face, arms, and body. Key to this portrait, however, is that thick, black contour, which records the essential shape and character of the woman’s body, drawn on top of it and overlapping her chest, hands, and thigh. It is fully intentional—as, we can assume, is also Matisse’s choice to leave the evidence of his reworking—almost as if it were a correcting measure to the original, more naturalistic portrait, essentially transforming the woman’s three-dimensional form into a flat plane and resulting in a visible tension between the two modes of representation at play.

If we apply this same logic to analyzing the High’s Woman Seated at Her Piano, alongside the knowledge of Matisse’s serial working method, it makes more sense to see the painting as one within a string of related works, negating the need to delegate it to a study based on arbitrary notions of finish that simply are not helpful nor worthwhile. To support this hypothesis, however, and in order better to understand the painting’s structure and how it was made, the High Museum took technical multispectral images of the painting in early August 2020 with the help of Atlanta Art Conservation and Renée Stein, the Michael C. Carlos Museum’s Chief Conservator, producing a suite of nondestructive visible, ultraviolet, and infrared images (fig. 9). While the painting exhibits major signs of reworking—especially in the positioning of the figure’s body and hands, where traces of earlier renderings remain—technical imaging revealed no evidence of underdrawings or later retouching.

This ultimately indicates that Matisse worked deliberately in paint without the help of a direct underdrawing on the canvas, adapting his composition as the painting took shape and purposefully manipulating the painted surface by covering up certain areas and rubbing away others to create the final state of his work. Rather than considering Woman Seated at Her Piano simply as a study for similar works of the same period, which appear more complex in their paint handling and composition, the High’s painting can be understood as yet another approach to the same subject, exemplary of Matisse’s continual play with varying modes of representing the natural world. But going beyond this preliminary consideration of the state of the High’s painting, its very subject, along with that of the larger series of piano paintings, begs to be reassessed.

Although we cannot place the High’s Woman Seated at Her Piano or its related paintings from the same period into a defined order as we only have approximate dates assigned to each work, it’s still interesting to consider how Matisse may have conceptualized the series, working from one canvas to another (or perhaps simultaneously) and making pointed changes along the way. If the High’s painting did come first, it certainly sets the stage for the others: it depicts the most closely cropped view of the pianist yet also the most constricted. A closer look reveals that she is effectively trapped, hedged in between the piano on the left and a rectangular brown cabinet on the right, which cuts into her upper back. Her body still holds a certain realistic weight, though—something that is uncommon for Matisse—her features sculpted and contoured so that she sits solidly in the center of the painting, clashing with the hard-edged space around her. She doesn’t quite fit or conform; her back is still separate from the rigid edge of the cabinet behind her, rounding outward toward the back of her chair. The scene itself is also spatially ambiguous, incorporating two perspectives pushed into one: the side of the piano presses solidly against the surface of the canvas, and the woman seems to be seated as if both were positioned directly in front of us, while simultaneously it appears as if the viewer is looking down onto the scene, with the top of the piano, its keys, and the seat of the chair all visible. It’s almost as if Matisse attempted to order or contain the tension produced by this series of contrasts by merging objects in space: the woman’s figure is enclosed by the harsh, black contour lines that trace the outline of her body, effectively flattening it, and even the bottom line of the piano edge curves around to meet the seat of the woman’s chair, which itself bleeds into the line of her back and the cabinet just behind.

Little Pianist, Blue Dress, Red Background at the Musée Matisse, Nice, continues the contoured, sculptural definition of the woman’s body as in the High’s painting, except this time, the scene is flipped so that the woman is turned to face the piano on the right side of the canvas. The paint is piled on even more thickly here, molded almost as if by palette knife, with the effect vacillating between clearer, more defined detail and areas of slippage, such as the neatly shaped body of the woman and piano, which are realistically portrayed in perspective, compared with the messy smear of the floral arrangement sitting atop the piano, which blends with the heavily patterned wall in the background. While Matisse still seems to play with ordering the figure of the woman within the surrounding space, aligning the contour of her back, or even the front of her face, with the yellow arch of the wall design behind her, the scene appears to be gradually opening up. Such is certainly the case in Pianist and Still Life at the Kunstmuseum, Bern, where the scene has expanded to show a wider view of the same room, this time switching back to the original orientation of the woman and piano and even incorporating a highly detailed Cézanne-esque still life front and center. Keeping the core of his subject the same, Matisse seems to flip through different styles of representation, remaining open to divergent techniques.

Things start to get strange in The Piano Lesson, though, where the scene, its objects, and its figures start to flatten out. Rather than maintaining a sculptural, weighted presence, the figures here (Matisse’s model Henriette and her two younger brothers) appear almost relief-like in comparison, with the woman and the boy standing behind her depicted in strict profile. In this way, Matisse’s painting comes very close to Cézanne’s Girl at the Piano (Overture to Tannhauser) (fig. 10), with its flat, horizontal approach to the scene. Painted over fifty years earlier and certainly a reference for Matisse, Cézanne’s version is drab in comparison, filled with muted grays, whites, and browns that exacerbate the severity of the girl’s rigid profile as she plays the piano, also situated against the left side of the canvas. But despite the bright color and rich patterns that envelop the room in Matisse’s The Piano Lesson, detail and definition are wiped away, with the figures appearing more like paper cutouts set against an artificial background than three-dimensional bodies occupying space. Just as in the High’s painting, the piano edge is pushed to the surface of the canvas (rather than set back slightly, as in Cézanne’s painting, revealing the angle of the room), but while the piano itself seems to be painted in legible perspective, giving a sense of extending into deep space, the rest of the room appears screen-like and uninhabitable, pieced together in a patchwork of contrasting patterned forms that give no support to the figures depicted within: the boy slides off the pink, formless chair, while the carpet itself seems to run off the bottom edge of the canvas. Even the back wall has lost all definition, with no clear indication of where one patterned wall ends and the next begins, separated only by the flat rectangle of brown cabinet situated behind the three figures.

Rather than representing a lively scene of music at play, Matisse’s The Piano Lesson is highly constructed. Composed not only of highly tuned color, the scene is also structured around hard edges and verticals that line up across the canvas, such as the straight piano back standing just against the red edge of the wall, the woman’s chair leg aligning with the front of the piano, or even the woman’s back pushed neatly in line with the left side of the cabinet, supported also by the front of the boy, who lingers just behind. Music may be attended to, but the scene is static, frozen, and silent. Instead, color and pattern take on life in Matisse’s painting, becoming the main subjects and focal points of the work, rather than the sound and expression of the figures themselves or the music being played. This is reflected even in the vase of pink flowers sitting on top of the piano, whose petals bleed into the floral design of the wall in the background.

Pianist and Checker Players at the National Gallery of Art represents the fullest iteration of Matisse’s exploration of color and pattern within this piano series, where even more details and juxtaposing patterns explode across the canvas, each vying for attention. The field of vision opens even further within the scene as its composition becomes more complex, seeming almost to wrap around the viewer in a spatially ambiguous way. Despite the woman and piano situated on a defined angle on the left, the walls don’t quite line up in clear perspective, appearing to flatten in the center background; neither do the bright red floor tiles, which seem to slide off the bottom right edge of the canvas, along with the decorative rug, due to their lack of grounding. Pattern and color compete with each other, leaving the viewer unable to focus on one aspect or another and creating a visual tension of push and pull that is reflected even in the contorted sculpture in the background—a cast of Michelangelo’s Dying Slave.9 Just as pattern and color become surrogates for life and music, the figures (Henriette and her brothers again) become surrogates for Matisse’s own family, as seen in comparison with The Painter’s Family from 1911 (fig. 11), which showcases the same checkerboard played by Matisse’s sons, Pierre and Jean, with Amélie and Marguerite situated in a similarly overwhelming, colorful, patterned room.

The ultimate result of Matisse’s series of piano paintings from 1924 to 1925, as well as of his Nice period work as a whole, is one of artifice: what may first appear as inviting, naturalistic scenes quickly give way to surfaces that are entirely inaccessible to the viewer. As described above, this is due in part to Matisse’s search for an overall sense of unity, in which he treats every part of a painting’s surface—figures and backgrounds included—equally, so that “the entire arrangement … is expressive.”10 What inevitably gets lost in this search for total expression, though, seems to be expression itself: these paintings are not reflections of the natural world but, instead, performances of it,11 “paintings about paintings” that show the transference of life and lived experience into art.12 Beyond this, though, these paintings reveal certain fallacies identified with realism, or naturalism—namely, that paintings aren’t necessarily windows onto the world despite what they might seem but, rather, layered and often abstracted representations of it, which may withhold expression entirely. According to Todd Cronan, “Matisse’s realism is conceived as anything but a direct contact with the natural world or bodies within it,” designating instead “his detached or observational attitude toward his medium and the world.”13

For an artist who seemingly based his entire production on the natural world, this may be a hard realization. Yet if the 1924–1925 series of piano paintings considered here reveals anything (and if my ordering of the five works isn’t completely farfetched), it is that Matisse’s “realism” was never that real to begin with, set within the highly contrived and constricted scenes that he meticulously constructed. As by far the most lifelike of the series showing the woman’s weighted presence within an intimate composition, the High’s Woman Seated at Her Piano is at the same time intentionally reworked into a pastiche, flattened by the unnatural black outline of her form over her initial rendering, and trapped in place. And despite the expansion of the scene and the proliferation of detail and color as the series progresses, we are left with only a heightened sense of artificiality, indicative perhaps of Matisse’s own unease with the representation of the world itself.