Fig. 1. Pie Safe, ca. 1830–1860, Unidentified Maker, Eastern Tennessee, walnut, tulip poplar, tin, and paint, 47 1/2 × 48 1/2 × 17 1/2 inches. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase with funds from the Fraser-Parker Foundation in memory of Nancy Fraser Parker, who loved the decorative arts, 2016.6. Photo: Michael McKelvey.

Early in 2016, the High Museum of Art acquired a pie safe with punched tin panels, constructed between 1830 and 1860 in Greene County, Eastern Tennessee (fig. 1). The primary wood is a beautifully grained walnut, with the structural (and hidden) portions of the safe made from the cheaper tulip poplar. The punched-tin panels on the front and sides show arrangements of urns, circles, hearts, compasses, and diamonds. These designs are picked out in blue paint applied to the tin, and details were further emphasized with red, yellow, and dark blue paint. Unlike many pie safes, this example seems to retain its original paint.

Pie safes have been an integral part of Southern furniture since the South was first settled and were designed for the short-term storage of fresh and recently cooked foods. The earliest known example, now in the collection of Colonial Williamsburg, was discovered near the Virginia–North Carolina border and dates to ca. 1680–1720 (fig. 2). Whereas the High’s safe uses punched tin to ventilate food while keeping it safe from insects and hungry rodents, the Williamsburg safe uses rough linen. It was fairly typical for early American examples to be covered in some kind of a textile, usually linen or cheesecloth, though some undoubtedly copied the British practice of using wooden panels drilled with multiple holes (fig. 3). It wasn’t until the 1830s that tin panels became popular. Many Southern safes had their feet placed in small containers of oil to prevent insects from climbing the legs, which, while effective at warding off ants, would had severely damaged the legs. (Many safes have had the damaged portions of their legs cut away, leaving them shorter than was originally intended. Fortunately, the High Museum safe does not show any evidence of damage from oil, nor is there any sign that the feet were ever cut down.)

-

Fig. 2. Pie Safe. Collection of Colonial Williamsburg, ca. 1680–1720.

-

Fig. 3. British Pie Safe. Photo by Nic and Kier.

The story of this particular pie safe does not begin in Eastern Tennessee but rather in Jonestown, a small town in southwestern Pennsylvania. Jonestown was largely settled by German immigrants, who became known as the Pennsylvania Dutch (after the locals’ misunderstanding of the immigrants’ word for “German”—Deutsch). The Jonestown craftsmen began producing a distinctive kind of furniture, the blanket chest, developing their own style and repertoire of motifs that drew heavily from the decoration they were familiar with in Germany. One eighteenth-century chest (fig. 4), now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, is a fairly standard example: a simple yellow pine box with a hinged lid, dovetailed cases, and bracket feet. Three arched panels on the front show large, stylized tulips bursting forth from small urns. In the central panel, a man sits on a horse between two swaying stems that meet to form a single tulip. Many have attempted to “decode” the meanings of these motifs, believing them to have a symbolic value. While they very well may have had a symbolic meaning when they first were used, decorative symbols rapidly become stylized. Eventually, they were probably used simply because people liked the way they looked.

To understand the relationship between these chests and a pie safe from Tennessee means following the story of Jonestown blanket chests to Virginia. The first large group of German immigrants arrived in Virginia in 1714. More followed soon after, either coming directly from Germany or moving south from Pennsylvania and Maryland and settling in Wythe County in the southwest of Virginia. At least one of those settlers brought a painted chest from Jonestown, as there exist at least thirty decorated blanket chests from Wythe County that show the unmistakable signs of influence from the Jonestown school of decoration. This chest from Winterthur (fig. 5) makes use of the same arch-headed panels with the urn and floral motifs from the Jonestown example. So close are the Wythe County blanket chests to their Jonestown predecessors that there are several reports of unscrupulous antiques dealers passing them off as Pennsylvania Dutch originals at higher prices.

-

Fig. 4. Dower Chest, 1700–1800, Berks Co., Pennsylvania, yellow pine and paint, 25 x 52 x 23 1/2 inches. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Mrs. Robert W. de Forest, 1933, 34.100.2.

-

Fig. 5. Blanket Chest, 1810–1825, Wythe Co., Virginia, tulip poplar, paint, and iron. Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library, Acc. 2010-46, Museum Purchase with funds provided by the Henry Francis du Pont Collectors Circle and partial gift of Roddy and Sally Moore.

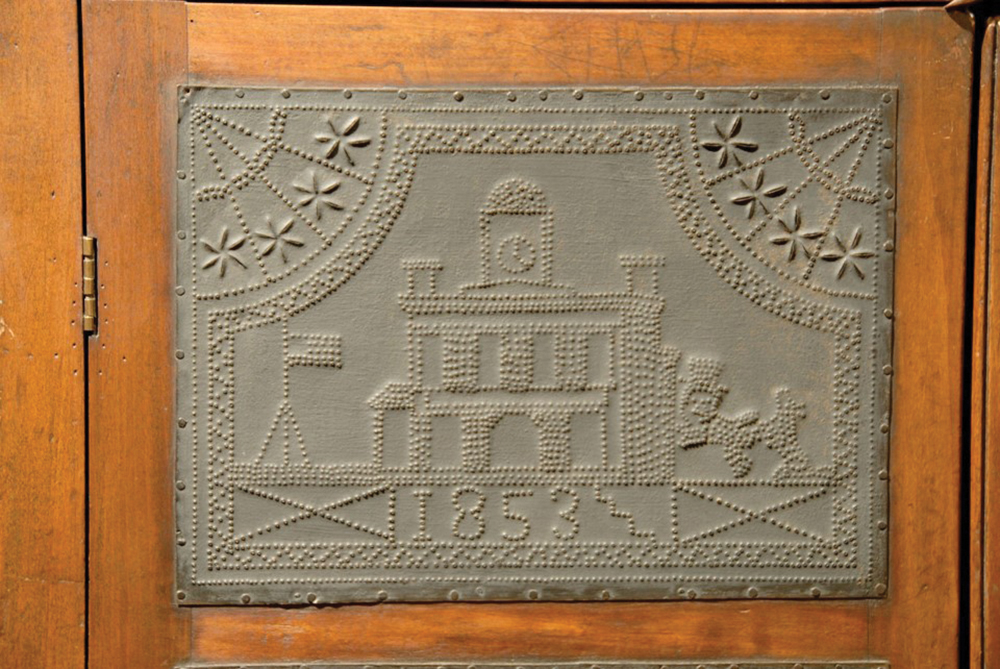

As for the connection between the chests and pie safes, this can be seen in the designs of punched-tin panels. As noted earlier, tin panels had become the popular choice for pie safes by 1830, and these panels became spaces for Tennessee craftsmen to exercise their imaginations. A Sullivan County safe (fig. 6), for example, displays punched tin panels with a courthouse and the date “1853” repeated on each of the six front panels (fig. 7); the side panels show flowers in a handled pot with the date “1852.”

In the town of Wytheville, Virginia, in the 1830s, the shop of Fleming K. Rich began producing a distinctive type of punched-tin panel larger than those made in other places (fig. 8). Where most other panels measured 10 x 14 inches, Rich’s shop produced examples made with either four 10-x-14-inch panels or two 20-x-14-inch panels crimped together. As a result, the wooden safes built to accommodate them were larger than usual. Rich’s panels popularized a very specific kind of decoration that drew directly from the motifs of Wythe County blanket chests. The designs are often based on an urn-and-grape pattern with differences appearing at the top of a central stalk. There we find single tulips, double tulips, sunflowers, diamonds, and stars. The decoration in the urns varies somewhat, as do the objects in the lower corners: there it is common to find fylfots, candlesticks, hearts, and stars (fig. 9). Other designs include diamonds, fylfots, urn-over-urn, and double urn–over–double urn. These examples bear a resemblance to the pie safe in the High’s collection, with large panels creating ample space for decoration and the principle motif of an urn. Furthermore, it is known that Fleming Rich’s shop offered a delivery service that would transport people and objects (including his own furniture) throughout southwestern Virginia and Eastern Tennessee.

-

Fig. 6. Pie Safe, Sullivan County, Tennessee. Museum of Eastern Tennessee History, Knoxville.

-

Fig. 7. Detail of Pie Safe from the Museum of Eastern Tennessee History, Knoxville.

-

Fig. 8. Punched Tin Decorated Safe, 1840–1860, Burgner Group, Greene or Washington Co., Tennessee, cherry, poplar, paint, and tin. Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, gift of Mary Jo Case, 5426a.

-

Fig. 9 (detail). Punched Tin Decorated Safe, 1840–1860, Burgner Group, Greene or Washington Co., Tennessee, cherry, poplar, paint, and tin. Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, gift of Mary Jo Case, 5426a.

Have we come to the origins of the High’s pie safe, then? Can we say that it was a Rich family construction that drew on the Pennsylvania Dutch iconography of Wythe County blanket chests and call it a day? Interestingly enough, our story is not quite over: there are still more links in our chain that connects Jonestown blanket chests to an Eastern Tennessee pie safe.

In 1841, Fleming Rich’s brother-in-law, George W. Moyers, wrote from Grainger County, Tennessee, to order thirty-five sets of tin panels for pie safes. He then sold those panels to individual furniture craftsmen who incorporated them into their own wooden pie safes. When I stumbled upon this piece of information, I thought that I had finally put all the pieces of the puzzle together. The High’s pie safe was surely built by an Eastern Tennessee woodworker who used the incredibly popular Wythe County tin panels “imported” from Virginia by George W. Moyers as decoration.

Yet I soon discovered that other craftsmen in three counties in Eastern Tennessee—Sullivan, Washington, and Greene counties—produced pie safes with large tin panels punched with rather similar designs to those from Wythe County, such as a safe from Washington County now in the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts. The popularity of the Rich family’s safes inevitably led to imitation. The panels in Tennessee, however, have specific motifs that are never found in southwestern Virginia examples: the Masonic arch, the square, and the compass. Thus, we find in Tennessee six variations on the Wythe panels: urn with Masonic symbols, urn-over-urn, urn with oak leaves, urn with grapes, urn with two circles, and hexagons. If we look at the pie safe in the Museum of Eastern Tennessee History in Knoxville (see fig. 6)—made in the second quarter of the nineteenth century and found by a picker around the border of Greene and Hawkins counties—we come quite close to the High’s example (As an aside, I would like to point out that the turquoise paint on these panels is not original.) The bottom half of the front panels shows an urn flanked by candlesticks and butterflies. Above the urn are diamonds and hearts; in the corners are the Masonic compasses distinctive to Eastern Tennessee. In the upper half, two wheels encircled by coronas like suns are surrounded by more butterflies and diamonds. The side panels continue on to show specifically Tennessean iconography. The upper panel has a butterfly and compass under a Masonic arch, with butterflies, hearts, and double diamonds on the sides. The middle and lower panels repeat the sun/wheel and urn motifs from the front.

The example from the Museum of Eastern Tennessee History has much in common with the High’s pie safe (fig. 10). Both can be categorized as an urn-with-two-circles type and show a profusion of Masonic compasses, butterflies, hearts, and diamonds. They are not, however, identical. The circles on the upper front panels of the High’s safe have no surrounding coronas and seem to be simple wheels. We find curious comma-shaped designs on this safe that do not appear at all on the other. The High’s pie safe does not have any Masonic arches, and instead its side panels repeat two circles over an urn.

Rather than a slew of uniform tin panels, we have many variations on a single theme; the Pennsylvania Dutch–inspired panels from Wythe County, Virginia, have developed a specifically Tennessean vocabulary. It is possible to securely anchor the High’s example within a group of fellow Eastern Tennessee pie safes.

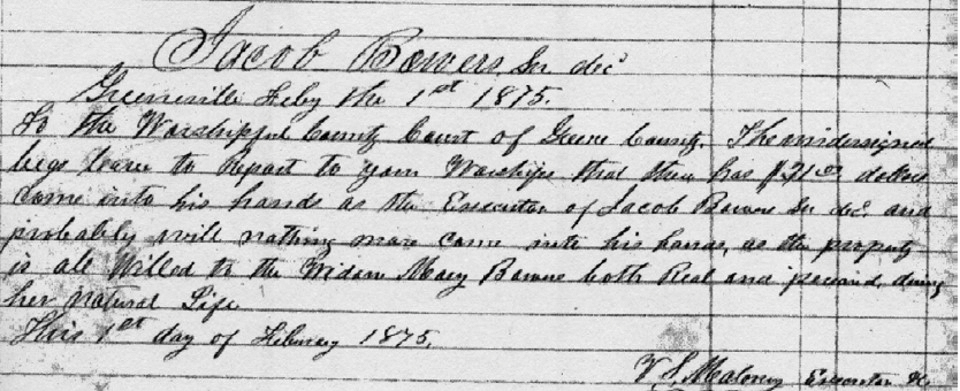

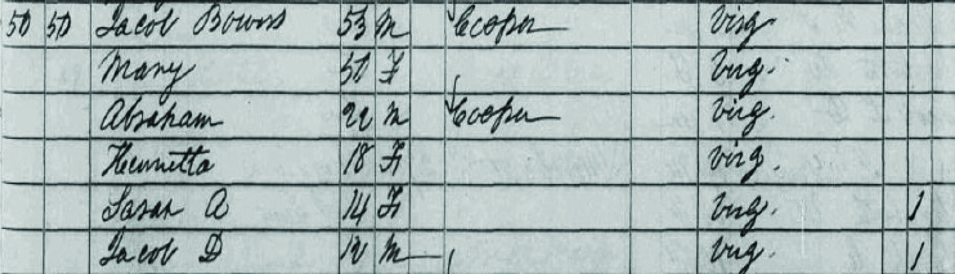

Though the specific origins of our safe are still shrouded in mystery and unlikely ever to be fully known, we do know that the safe was passed down in the Bowers family of Greene County. German in origin, the family immigrated first to Pennsylvania and then to Virginia. Jacob Bowers was born in Virginia around 1797 and, having lived a long life, died shortly prior to February 1, 1875, based on the inventory of his estate that can still be found in the Greene County records (fig. 11). A Greene County census of 1850 (fig. 12) shows not only that Bowers was a cooper—someone who makes utensils, barrels, and casks out of wood—but also that he had relocated to Tennessee sometime before the middle of the nineteenth century. Though he attested that his parents were immigrants, he himself was a US citizen. It is tempting to believe that Jacob Bowers could have been the one to order a pie safe from a local craftsman with panels that perhaps looked like those he was familiar with from his residence in Virginia and that, after his death, the safe began to pass down through the family. Unfortunately, Bowers’s estate inventory is frustratingly brief: he wills all property and real estate to his wife, Mary. Upon her death, it stipulates, the property will be divided amongst their six children. As a result, there is no list of his personal belongings, no inventory that could tell us whether or not he had a pie safe in his possession at the time of his death. We are forced, then, to remain strictly within the realm of conjecture.

-

Fig. 11. Estate inventory of Jacob Bowers, February 1, 1875.

-

Fig. 12. Census of 1850, Greene County, Tennessee.

Yet it is fitting to conclude with Jacob Bowers. Here we have a man whose parents immigrated from Germany to Pennsylvania, where they certainly would have been familiar with the tradition of Pennsylvania Dutch painted chests and perhaps even owned one themselves. Bowers was born in southwestern Virginia, another Germanic settlement, where the tradition of painted chests led to the flowering of similar iconography in the punched-tin panels of wooden pie safes. Bowers moved to Eastern Tennessee, where the popular Wythe County tin panels inspired craftsmen to create their own imitations of the designs with the addition of local iconography. In his life, we can trace the entire story of the High Museum’s pie safe that would be handed down in his family until the twentieth century.

—Nicole Corrigan, Emory University, Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Graduate Fellowship Program in Object-Centered Curatorial Research, 2016