Attributed to Lorenzo Costa (Italian, ca. 1460–1535), St. Roche, ca. 1500, tempera on panel, each panel 14 7/8 x 5 1/2 inches. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, gift of the Samuel H. Kress Collection, 58.40a, 58.40b.

Description

In 1958, the Samuel H. Kress Foundation donated thirty-eight paintings to Atlanta’s High Museum of Art. This donation established the young institution as one of eighteen regional centers for the display of European Renaissance and Baroque art. Included within the landmark donation were eight small, early sixteenth-century paintings in tempera on panel. The panels feature saints displayed in classicizing architectural niches, each measuring just over fifteen by five inches.1 The panels are currently arranged in pairs in gilded frames that date to the mid-twentieth century (fig. 1). The frames have a somewhat neutral profile equally at home within the stylistic categories of Gothic and Renaissance. Even with no knowledge of the panels’ original display context, considering the perspectival construction of the architecture indicates that the panels were originally displayed as opposite columns. Such an arrangement would have formed the outer edges of a monumental altarpiece. The central panel would have likely featured a common devotional subject such as the Coronation of the Virgin or a Virgin enthroned with local saints. The purpose of the small panels arrayed along the sides of the altarpiece would have been to feature saints associated with specific aspects of Christian experience, referencing potential difficulties in which the devotee would pray for assistance.

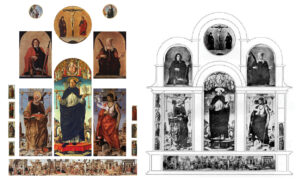

A precedent for a devotional arrangement featuring lateral pilasters comprising varied saints can be found in Giovanni Bellini’s Coronation of the Virgin, dating to the early 1470s, painted for the church of San Francesco at Pesaro (fig. 2). In addition to their traditional attributes, the High Museum’s Eight Saints are identified by visually prominent inscriptions in a northern Italian dialect. Saint Julian the Hospitaller and Saint Christopher would have most likely been in the topmost position of the two pilasters framing a central devotional panel (fig. 3). Both of these saints’ hagiographies are associated with travel: Julian ran a pilgrim’s hospital as penance for having mistakenly murdered his parents, a sacrifice that ultimately led to absolution; St. Christopher carried an apparition of the Christ Child as he performed his customary charity of transporting pilgrims across a dangerous river.2 The monastic saints Nicholas of Tolentino and Vincent Ferrer wear the robes of their respective orders as they carry books and scrolls, inspiring the faithful to the poverty and erudition of monastic life (fig. 4).3 Saints Roche and Sebastian were typically worshipped for their potential to alleviate the plague (fig. 5). They inspire the supplicant’s identification by displaying the wounds they suffered by centurion’s arrows and illness. Saints Catherine of Alexandria and Lucy display objects representing the torture that preceded their martyrdom (fig. 6). Venerated for having resisted the advances of pagan suitors, both of the early Christian saints served as models of feminine virtue in fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Italy. The aforementioned iconographic pairings are not reflected in the panels’ current framing. Even though they seem to have been framed to evoke the effect of a devotional diptych, there is no thematic relationship between the saints paired within each frame. The present arrangement also confuses the niches’ perspectival structure.

-

Fig. 1. Attributed to Lorenzo Costa (Italian, ca. 1460–1535), St. Roche, St. Lucy, ca. 1500, tempera on panel, each panel 14 7/8 x 5 1/2 inches. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, gift of the Samuel H. Kress Collection, 58.40a, 58.40b.

-

Fig. 2. Giovanni Bellini (Italian, ca. 1426–1516), Coronation of the Virgin, ca. 1470, oil on panel, approximately 16 1/2 x 11 feet, including additional panel (not shown). Musei Civici di Pesaro, Italy. Image source: Scala/Art Resource, NY.

-

Fig. 3. Attributed to Lorenzo Costa (Italian, ca. 1460–1535), St. Julian, St. Christopher, tempera on panel, each panel 14 7/8 x 5 1/2 inches. High Museum of Art, gift of the Samuel H. Kress Collection, 58.38a, 58.41a.

-

Fig. 4. Attributed to Lorenzo Costa (Italian, ca. 1460–1535), St. Nicholas of Tolentino, St. Vincent Ferrer, tempera on panel, each panel 14 7/8 x 5 1/2 inches. High Museum of Art, gift of the Samuel H. Kress Collection, 58.38b, 58.41a.

-

Fig. 5. Attributed to Lorenzo Costa (Italian, ca. 1460–1535), St. Roche, St. Sebastian, tempera on panel, each panel 14 7/8 x 5 1/2 inches. High Museum of Art, gift of the Samuel H. Kress Collection, 58.39a, 58.40a.

-

Fig. 6. Attributed to Lorenzo Costa (Italian, ca. 1460–1535), St. Catherine of Alexandria, St. Lucy, tempera on panel, each panel 14 7/8 x 5 1/2 inches. High Museum of Art, gift of the Samuel H. Kress Collection, 58.38a, 58.40a.

Provenance and Attribution

A memorandum from 1935 found in the National Gallery of Art Archives, Washington, DC, records a payment of $309,000.00 by Samuel H. Kress (1863–1955) to the Florentine art dealer Count Alessandro Contini-Bonacossi (1878–1955).4 The single bill of sale includes twenty-nine works of art. The High Museum’s eight small panels of saints, sold as works by Lorenzo Costa, are listed alongside paintings by Perugino, Lorenzo Lotto, Tintoretto, and Veronese. Sadly, there is scarce archival record of Contini-Bonacossi’s business transactions.5 Therefore, most of the works that passed through his hands cannot be traced prior to their sale to collectors such as Kress. Reviewing this list of twenty-nine works—and the significant names it features—provides an example of Kress’s collecting approach. Expansive purchases covered a range of artists and styles and were inspired by the optimism of impressive attributions.

My research into the High’s Eight Saints focuses on the contributions of the eminent twentieth-century art historian Roberto Longhi (1890–1970). Longhi worked as an advisor for Contini-Bonacossi beginning in the 1920s.6 While it is not possible at this juncture to recover documentation of the panels prior to their ownership by Contini-Bonacossi, Longhi’s published opinions on the attribution and provenance of the works afford a productive line of inquiry to further interpret the panels for visitors to the High Museum.

The topics of Longhi’s study as an art historian cover a wide range. In 1911, he completed a dissertation on Caravaggio before studying with Adolfo Venturi (1856–1941) in Rome, which led to Longhi’s longstanding affiliation with the magazine L’Arte. An article published in 1914 was the genesis of one of the scholar’s most famous works, a monograph on Piero della Francesca.7 Longhi therein refuted Bernard Berenson’s dismissal of the artist to incorporate the master into the canon of great Quattrocento painters. Despite this particular difference in opinion with Berenson, Longhi joined his art-historical predecessor as a dedicated practitioner of connoisseurship.8 This effort is reflected above all in Longhi’s foundational study, the Officina Ferrarese, first published in 1934.9 In a similar manner to Berenson’s quest to establish a definitive corpus of paintings for regional Italian schools from the 1890s onward,10 Longhi sought to create a clear record of artistic achievement for artists working in and around the city of Ferrara by responding to a landmark exhibition organized in Ferrara’s Palazzo dei Diamanti in 1933.11 It is in this scholastic context that Longhi published his opinion on the High Museum’s Eight Saints.

Longhi begins his analysis of the Ferrarese school with the standard art-historical trope of describing the international Gothic as an infantilizing prelude.12 From there he develops a focused analysis of the primary figures of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Pisanello, Jacopo Bellini, and Piero della Francesca are cited as passing influences who contributed to the stylistic development of the painters of Ferrara. Longhi’s discussion of the fifteenth century focuses on the painters Cosmè Tura (ca. 1430–1495), Francesco del Cossa (ca. 1435–1477), and Ercole de’ Roberti (ca. 1455–1496). Lorenzo Costa (1460–1535), the artist to whom the High Museum’s panels are attributed, is briefly discussed in relation to the three aforementioned artists. The reconstruction of monumental altarpieces that have survived only in fragments is a recurring motif in Longhi’s research method. Beginning with the painter Cosmè Tura, Longhi uses the example of the Roverella altarpiece formerly in the Bolognese church of San Giorgio fuori le Mura to showcase the artist’s heavily ornamented style (fig. 7).13 As a courtier of Borso d’Este, Duke of Ferrara, Longhi interprets Tura as representative of a “feudal, Ghibelline temperament” that established the “specific physiognomy” for Ferrara in contrast to other schools of north Italian painting.14 In the central panel, the monumental stone seat on which the Virgin and Child are enthroned showcases the painter’s artistry. Examples of the myriad engaging details are seen in the festoons of grapes hanging from the side of the throne and the bronze angels suspending a large shell adorned with pearls over the Virgin’s head. Longhi cited three small roundels already in American collections as the final components that completed his proposed altarpiece reconstruction.15

A cogent example of Ercole’s artistry is seen in the architectural complex of the heavy stone throne. The conceit of the throne supported on thin crystal stilts with a detailed landscape in the background is a relevant motif for Lorenzo Costa’s oeuvre. While praise for Ercole’s prowess is certainly warranted, Longhi’s exaltation of individual genius figures and his fetishization of local schools are a bit jarring to the twenty-first-century reader.21 This hagiographical tone gives a clear indication of Longhi’s project: he sought to establish the canon of artists and painters in Ferrara and integrate them into the wider currents of European art history. As is made clear by Longhi’s praise for Ercole, some figures are more important than others in his estimation of this tide of crosscurrents. The artists Francesco del Cossa and Lorenzo Costa are minor figures in the ambit of Ercole de’ Roberti in the architecture of Longhi’s criticism. Longhi discusses Cossa for his “vigor, dramatic timbre, and taste for powerful, elemental, pared down colors.”22 With regards to this artist, Longhi’s concern is the reconstruction of the Griffoni altarpiece, formerly in the church of San Petronio in Bologna (fig. 9).23 He sees the polyptych as a joint effort by Cossa and Ercole. To arrive at this conclusion, Longhi builds on the early research of Gustavo Frizzoni, who conceived of the altarpiece as consisting of three panels by Ercole presently in Milan’s Pinacoteca di Brera.24 Large-scale panels of Saints Peter and John the Baptist flanked a central panel of Saint Vincent. A predella panel now in the Vatican was thought to complete the ensemble. Based on the varying heights of the three central panels, Longhi concluded that the altarpiece must have had a variegated tripartite arrangement common to north Italian altarpieces of the preceding century, as seen in the works of the Venetian painter Antonio Vivarini.25

According to Longhi, the three panels of Frizzoni’s reconstruction would not have been large enough for the vast space of a side chapel in the church of San Petronio.26 He addressed this presumed deficiency by adding three panels by Cossa now in American collections to the altarpiece. At the time of Longhi’s writing, their provenance was not yet accounted for.27 Crowning the ensemble is a crucifixion roundel formerly in the Lehman Collection and now in Washington’s National Gallery. Two panels belonging to the National Gallery’s Kress Collection showing the saints Liberale and Lucy completed the arrangement on both sides of the central roundel. One final element of Longhi’s reconstruction for the Griffoni altarpiece establishes a precedent for the High Museum’s Eight Saints. On either side of Ercole’s panels of Saints Peter and John the Baptist, Longhi proposed two pilasters formed of panels displaying saints in fictive niches. He noted that the six small panels had been variously attributed to Ercole and Cossa, and the same criteria apply to the ensemble’s proposed predella in the Vatican.28 At the time of Longhi’s writing, the panels proposed for the pilasters were in the collections of the Louvre, the dealers Duveen and Contini-Bonacossi, and an Italian private collection. They had been variously attributed to Ercole de’ Roberti and Francesco del Cossa.29 Authoring a compromise loyal to the methods of connoisseurship, Longhi responded to the disputed attribution history to propose an altarpiece comprising components by the two artists in question.

While Francesco del Cossa is cast as Ercole de’ Roberti’s precursor, who would later be surpassed by his younger peer, Lorenzo Costa is described as an inferior contemporary to the genius Ercole. Considering early works of uncertain provenance and attribution, such as the scene from the story of the Argonauts in Padua’s civic museum, Longhi sees “savage and less intelligent humanity” in Costa’s figures in comparison to Ercole’s (fig. 10).30 As is often the case with artists even in more recent centuries, Costa’s early activity is scarcely documented. Longhi clearly states his ambition to work with this fraught early period, aiming for a “rediscovery of a decade of the painter’s activity, who, born in 1460, must have been active in Bologna by 1480.”31 He further notes that most studies of the artist begin with the more certain works documented from 1488 onward.32 In his discussion of Costa’s early period, Longhi frequently cites the record of Berenson’s attributions, in works such as the Saint Sebastian in Dresden (fig. 11), which Berenson describes as a painting begun by Roberti and completed by Costa. The signature in Hebrew that bears Costa’s name firmly places the work within the artist’s oeuvre.33 In opposition to Berenson’s attribution, Longhi discerns the nascent hallmarks of Costa’s own style in the diminutive figure of the Roman centurion in the background. Longhi thus concludes that Costa painted a work in the manner of Ercole to accommodate a patron’s taste for that artist’s style or perhaps to fulfill a commission for a painting that would be paired with a work by Ercole.34

-

Fig. 10. Lorenzo Costa (Italian, ca. 1460–1535), The Argonauts, 1484–90, oil on panel, 18 1/2 x 23 feet. Musei Civici, Padua, Italy. Image source: Alfredo Dagli Orti/Art Resource, NY.

-

Fig. 11. Lorenzo Costa, St. Sebastian, 1480s, tempera on poplar, 67 x 23 inches. Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden. Photo: Hans-Peter Klut. Image source: bpk Bildagentur/Art Resource, NY.

Longhi features the altar panel associated with the church of Santa Maria delle Rondini as an encompassing example of Costa’s early style (fig. 12). The painting was formerly displayed in the Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum (now the Bode Museum) in Berlin, where it was destroyed in the Second World War. The panel’s heterogeneous attribution history serves as an example of the complexity of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century connoisseurship studies. The Bolognese scholastic tradition took the painting to be a work by Galasso,35 while Berenson hesitatingly attributed it to Costa.36 The basis for these attributions is the seventeenth- and late eighteenth-century art-historical scholarship of Cesare Malvasia (1616–1693) and Girolamo Baruffaldi (1740–1817).37

Longhi critiques his contemporary Lionello Venturi (1885–1961) (son of Adolfo) for not recognizing the hand of Costa in his description of a “primitive education in the manner of Tura, lightly modified under the reform of Roberti” in the altarpiece.38 Venturi’s stance on the panel effectively illustrates the manner in which the works of the three principal artists of the fifteenth-century Ferrarese school—Cosmè Tura, Ercole de’ Roberti, and Lorenzo Costa—seem to blend together through time’s obfuscations. In fact, Longhi draws on the traits shared in common by these three artists to fully articulate his attribution of the panel to Costa. He cites the fantastic architecture at the base of the throne as a sign of Ercole’s influence; in the saints he sees a certain “rustic quality” in the manner of Tura.39 At the confluence of these minutely varied styles, Longhi describes a unified structure created by the young artist, “già robertiana; per di più, già costesca.”40

In keeping with the precedents asserted in his reconstruction of the Griffoni altarpiece, Longhi notes Filippini’s citation of the eighteenth-century guidebook author Baruffaldi, who observed that a polyptych displayed in Santa Maria delle Rondini had eight small figures of saints in the pilasters.41 Longhi unequivocally identifies the saints as the High Museum’s Eight Saints, in the collection of Contini-Bonacossi at the time he was writing the Officina Ferrarese. He dates the figures to 1485 on stylistic grounds.42 In the first series of ampliamenti published to the Officina Ferrarese in 1940, Longhi augmented the supposed Santa Maria delle Rondini altarpiece even further, noting that an altarpiece of this size would not have been without a predella scene (see fig. 12).43 He saw a worthy candidate in a series of panels representing the Funeral of the Virgin, also a part of the Kress Collection and now in the North Carolina Museum of Art in Raleigh. While Longhi notes that there are some discrepancies in the sizes of the panels, he states that the dedication of the confraternity’s church to the Virgin was sufficient grounds for the panels to be associated with the altarpiece formerly in Berlin.44 This hypothesis was credibly refuted by Edoardo Arslan with a brief article published in the Rivista d’Arte in 1959, in which he noted that the panels in Raleigh correspond more closely both in size and subject matter to a panel depicting the Assumption of the Virgin in the Abbey of Monteveglio outside Bologna (fig. 13).45

Before looking further into the attribution and provenance of the High Museum’s Eight Saints and the Santa Maria delle Rondini altarpiece, it is worth briefly outlining the life of the artist to whom Longhi attributed the work. Though he was consigned to a minor role in Longhi’s account of the flowering of the Ferrarese school, Costa was in fact a highly successful artist. Born in 1460, by 1483 Costa was working for the Bentivoglio family, who usurped power from the papal legates to rule Bologna in the early fifteenth century.46 In 1508, he was summoned to Mantua by the Marquis Federico Gonzaga and within a year was granted citizenship to that city. Shortly thereafter he attained the honorable position of court artist with the support of an annual stipend, thereby succeeding his renowned predecessor, Mantegna. As an indication of his elevated status, the artist also held minor diplomatic posts, serving as an ambassador of the Bolognese senate at the election of Pope Julius II in 1503 and as the head of the Ufficio del Sale in Mantua beginning in 1519.47

An itinerary through Bologna’s churches offers the opportunity to survey the breadth of the artist’s accomplishments. A sumptuous chapel dedicated to the memory of the Bentivoglio family is a testament to the local rulers’ high esteem for the artist. The chapel is found in the ambulatory of the church of San Giacomo Maggiore, where iron gates cordon off a private devotional space, the walls of which are covered with frescoes by Costa. On the right-hand wall, the Bentivoglio Madonna is painted in fresco, enthroned beneath a fictive loggia that extends around the circumference of the room.48 Giovanni II Bentivoglio (1463–1506) and his wife Ginevra Sforza (1440–1507) kneel in prayer on either side of the Virgin’s commanding classical throne; eleven of their twelve children stand below. Costa’s signature is prominently displayed at the end of an inscription that commends the family to the protection of the Virgin. The remaining walls are painted with allegories in the form of Petrarchan triumphs.

The Ghedini altarpiece features a striking interpretation of the Virgin’s throne: the mother and child sit on a stone seat oddly positioned at the midpoint of the columns supporting a classical loggia. A velvet brocade cloth of honor hangs behind the Virgin from the iron bars that span the width of the loggia. Below the Virgin, Saints Augustine and Posidonius break their contemplation to behold the viewer. Closer to the throne, John the Evangelist also returns the viewer’s gaze while Francis beholds the Virgin and displays the wounds of the stigmata. At the saints’ feet, two small angels play instruments as they frame one of the painting’s most curious aspects. In the base of the Virgin’s throne, a sharply delineated aperture opens onto a distant, verdant landscape. Costa signed his name on the upper border of the opening. The fantasies of crystal columns and the narrow opening discussed previously with regard to Ercole de’ Roberti’s paintings have been pared down and incorporated into a more believable architectural framework. By leaving his signature on the upper edge of an open void leading to a lush landscape, Costa asserts his skill as he thematizes painting’s mimetic performance.

In light of Costa’s own engagement with conceptual frameworks in his portrayal of the Virgin’s throne, I will briefly describe the original fifteenth-century frame that still contains the large painting of the Virgin enthroned.50 Though not necessarily in terms of their conceptual valence as explored by Costa in the Ghedini altarpiece, frames are a crucial issue for my investigation of the provenance, attribution, and original display context of the High Museum’s Eight Saints. Considering the gilded frame that contains the Ghedini altarpiece, it is important merely to note its simplicity. It has a straightforward, pared-down organizational structure: two pilasters flank the painted panel; the Ghedini family’s arms are displayed at the bottom corners. Classical foliate designs radiate outward from a central urn in the frieze below the architrave. A similar foliate design extends across the breadth of the altarpiece between the coats of arms. Surveying the panels by Costa that are still in their original locations in the churches of Bologna, it is quickly recognizable that many of the altarpieces were reframed throughout the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries. Often, these frames preserve the altarpiece’s original format but lack the harmony of design seen between the fictive architecture of the Ghedini altarpiece and the classical ornament carved on the surface of its frame.

Another large-scale altarpiece still in its original location in Bologna offers the opportunity to reflect on a thematic concept relevant to the High Museum’s Eight Saints, regardless of their authorship status. St. Jerome Enthroned, still to be seen in the church of San Petronio, shows the early Christian scholar seated on a monumental stone throne at the center of a classical loggia (fig. 15).51 The sides of the throne are surmounted by sculptures of allegorical figures standing atop spheres, and below these ornaments, two more fictive statues stand in niches in the uppermost reaches of the throne. As in the Ghedini altarpiece, an ordered, harmonious, and yet fantastic system of architecture is developed to enshrine the saint. Devotion is inspired through a complex interrelation between figure and architecture. Engaging details such as the aperture beneath the Virgin’s throne and the statues in niches just above Saint Jerome emphasize the playful dynamics of this thematic construct. Though their authorship remains uncertain, and it is not possible to identify exactly which altarpiece they once belonged to, the recurring motif of interaction between figure and architecture in Costa’s Bolognese oeuvre offers an appropriate lens for interpreting the High Museum’s Eight Saints.

The National Gallery of London has the greatest concentration of works by Lorenzo Costa in a single institution. Museum galleries offer the opportunity to view works up close in the interest of the stylistic comparisons that were the staple of Berenson and Longhi’s scholarship. In addition to large-scale panels similar to the Ghedini altarpiece, the collections include a portrait and genre scene. The portrait of the court poet and medicinal writer Battista Fiera showcases Costa’s ability to paint in fine detail (fig. 16).52 Individual traits such as birthmarks and laugh lines realize a penetrating likeness. Likeness seems to have been of less importance in The Concert, painted around 1485, but the detailed representation of clothing, jewelry, and musical instruments is no less masterful (fig. 17).53 Whether it depicts a genre scene or a true portrait of members of the Bentivoglio family, it was likely painted for the decoration of a music room or studiolo.54

-

Fig. 16. Lorenzo Costa, Battista Fiera, 1507–08, oil on panel, 20 x 14 inches. National Gallery, London, NG2083.

-

Fig. 17. Lorenzo Costa, The Concert, ca. 1488–90, oil on panel, 7 1/2 x 30 inches. National Gallery, London, NG2486.

Especially relevant to a consideration of the High Museum’s panels is the National Gallery’s altarpiece from the oratory of San Pietro in Vincoli of Faenza (fig. 18).55 The altarpiece has survived in five separate panels and was previously displayed at the National Gallery in a nineteenth-century frame designed to approximate the appearance of a complete altarpiece. The curatorial staff of the National Gallery recently made a decision to reframe the panels individually, an approach that will be discussed in greater detail in the following pages.56

Establishing the context and ambitions of Roberto Longhi’s scholarship and the historical situation of Costa enables a more focused reconsideration of the attribution of the High Museum’s Eight Saints. As has previously been stated, their provenance cannot be traced farther back than their ownership by Contini-Bonacossi. There is scant archival record of the activities of this dealer and, at the time of this writing, Longhi’s own archives in Florence have not yet been made available to researchers. On what basis did Longhi ascribe the small panels to the pilasters of the lost altarpiece of Santa Maria delle Rondini? Francesco Filippini’s 1933 article “Pittori ferraresi del rinascimento in Bologna,” cites a brief scholastic record that can potentially account for the appearance of an altarpiece in the oratory of Santa Maria delle Rondini.

Santa Maria delle Rondini has a rather romantic foundation story common to the churches and oratories erected by Italian Renaissance confraternities—organizations that promoted charitable work and devotional activities for laypeople. In a southwestern corner of the city, near the Porta Saragozza, an image of the Virgin was hung on a tree where sparrows—rondini—were in the habit of gathering.57 Over time, miracles came to be attributed to the image of the Virgin. Eventually a confraternity was organized and a small church, or oratorio, was built to protect the miraculous object. The organization would have been one among many in a city of Bologna’s size. Under the turmoil of Napoleonic rule, the confraternity was disbanded in 1798 and its property was sold.58 The oratory itself was demolished in 1910 and the original miraculous image was transferred to a nearby church.59

Returning to Longhi’s published source for the provenance of the Santa Maria delle Rondini altarpiece, in a review of the 1933 exhibition of Ferrarese painting, Filippini attributes the painting to the artist Galasso. Filippini cites Cesare Malvasia,60 and a selection of eighteenth-century guidebooks to account for the appearance of the high altar of the confraternity’s oratory.61 The most important of Filippini’s citations comes from Girolamo Baruffaldi’s Vite dei Pittori e scultori Ferraresi.62 Baruffaldi describes a painting that “represented a Madonna on a pedestal, with most beautiful fictive reliefs, with the Saints Francis and Jerome on the right and Bernard and George on the left, and eight more small saints in two rows on the sides.”63 Filippini immediately notes that the painting, presumed to be lost at the time of his writing, corresponds exactly with the Virgin enthroned then in Berlin. The Berlin panel was purchased by the Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum from the Edward Solly Collection in 1821.64 Filippini praises the work for the realism of the saints’ faces, “which seem to be like portraits from life,” as in the figure of Saint Bernard. At this juncture may be found the potential genesis of Longhi’s reattribution of the work to Costa, as Filippini cites the face of Bernard in the Berlin panel as an inspiration for Saint Francis in Costa’s Ghedini altarpiece.65

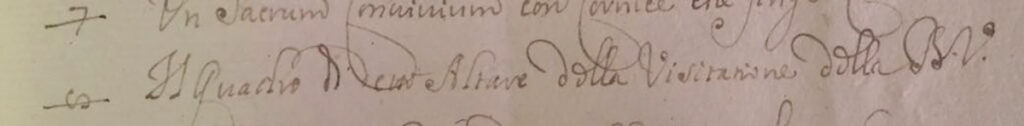

A research visit to the state archives of Bologna offered the opportunity to read through a 1671 inventory of the confraternity of Santa Maria delle Rondini.66 It is reasonable to assume that an oratorian setting would have been host to only one altarpiece on the scale of Longhi’s proposed reconstruction. Such an object would have most likely been displayed over the high altar. The inventory of 1671 does not list any works with a close correspondence in subject matter to the painting described by Baruffaldi and later cited by Filippini and Frederico Zeri. The painting over the oratory’s high altar is listed as “della Visitazione della S.S.V”—a visitation scene rather than a Virgin enthroned (fig. 19). Additional sections of inventories list the contents of specific spaces in and around the oratory, such as the sacristy, the “residenza,” and the “Camera della S.S.V,” (likely an antechamber where the original miraculous image of the Virgin was displayed). An additional list enumerates a set of items “en consegna del guardiano [della] chiesa.”

Throughout the 1671 inventories, a number of devotional paintings are mentioned. Most importantly, the confraternity’s main devotional space featured a Visitation scene over the high altar. The space also contained a crucifix, an altarpiece with a depiction of the Annunciation in an unspecified location, and lastly, “a small painting of the Blessed Virgin above the exit.”67 The “Camera della S.S.V” contained a painting of the Assumption. Finally, three works are listed in the sacristy: two “ancone dipinte all’antica” and an “ancona anessa pure al muro” [two altarpieces painted in an old style and an altarpiece simply affixed to the wall]. One of the two paintings done “in an old style” is described as having “diverse saints.” The “altarpiece displayed directly on the wall” featured Saint John the Baptist. An additional painting of the Virgin and Child is noted nearby. There is also the mention of two “wings” depicting Saints Anthony and Charles. One of the early eighteenth-century guidebooks cited by Filippini specifies that the Berlin panel attributed to Costa was displayed in a room near the organ.68 This particular space was not demarcated in the 1671 inventory.

As for the discrepancy in subject matter concerning the painting over the high altar, it is possible that a new altarpiece was commissioned for the oratory by 1671. Could the “painting in an old style” with “various saints” refer to the painting that found its way to Berlin in the collection of Edward Solly? In the 1670s, describing an altarpiece as painted “all’ antica” would have most likely referred to a fourteenth- or early fifteenth-century polyptych, rather than a panel painting from the time of Lorenzo Costa.69 While the “diversi santi” are a tantalizing hint, none of the works mentioned in the 1671 inventory has a close enough correspondence to the Berlin panel for the work to be definitively associated with the confraternity. I have not yet been able to find any documentation of the sale of works from the confraternity when the order was suppressed in 1798. There is also a conflict with Longhi’s dating of the panels. The records of the confraternity record the first miracles of the image of the Virgin taking place in 1500. Records of donations to the confraternity also begin at this date.70 Longhi’s stylistic dating of the High Museum’s Eight Saints to the 1480s therefore precedes the foundation of the organization.

An additional avenue that can be pursued to take a stance on the attribution of the High’s panels is to try one’s own hand at the techniques of connoisseurship upheld by the likes of Berenson and Longhi. The San Pietro in Vincoli altarpiece in London’s National Gallery has a framing situation relevant to the display and interpretation of the Eight Saints. It also offers the opportunity to encounter the full magnitude of Costa’s talents as a painter.71 The central panel of the altarpiece explores similar concepts to those seen in the Ghedini altarpiece in Bologna. The Virgin sits before a cloth of honor on a stone throne surrounded by four adoring angels. Beneath the Virgin an aperture surmounted by the artist’s signature opens onto a distant landscape. In this instance, it is an idyllic coastal scene with a band of travelers close at hand and a fantastic city in the far background. Like the Portrait of Battista Fiera and the Concert displayed in London’s National Gallery, the San Pietro in Vincoli altarpiece, currently in storage, displays Costa’s skill that enabled him to attract elite patrons such as the Bentivoglio. Looking closely at details such as hands and faces in comparison with the High Museum’s panels emphasizes the marked difference in quality. In the High’s panels, there is little to no articulation of volume in details such as the hands. For the most part, a uniform application of paint represents the back of the hand and the individual fingers, as seen in the left hand holding Saint Lucy’s chalice. Across all eight panels, the faces are represented in a similarly cursory manner. The careful attention to detail and anatomical accuracy of the saints and angels in the San Pietro in Vincoli altarpiece suggests the hand of a different artist.

The discrepancy in quality between the High’s panels and the London altarpiece could potentially be addressed by Longhi’s attribution of the High Museum’s panels to the artist’s formative years. In his estimation, Costa’s lack of experience would account for the cursory representation of anatomical details. The argument could also be made that as lateral panels for a large-scale devotional altarpiece, the High Museum’s Eight Saints were intended to be viewed from a significant distance and therefore an exacting level detail would not be necessary. However, comparison with other works attributed to Costa of a similar scale to the High’s panels, such as The Adoration of the Shepherds with Angels in the National Gallery, London (fig. 20), and The Story of Susannah: The Elders as Judges at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore (fig. 21) betray a heightened anatomical clarity that is clearly divergent from the technique of the artist who painted the High Museum’s Eight Saints.

-

Fig. 20. Lorenzo Costa, The Adoration of the Shepherds with Angels, oil on wood, 20 1/2 x 14 1/2 inches. National Gallery, London, NG3105.

-

Fig. 21. Lorenzo Costa, The Story of Susannah: The Elders as Judges, 1488–90, tempera on panel, 17 3/8 x 17 1/4 inches. The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, 37.476.

How did the art historians working in the middle decades of the twentieth century arrive at their conclusions? The object file at the High Museum includes an attribution justification, or “expertise” by Lionello Venturi, who praises the panels for the “elegance of their attenuated figures” and their “preciousness of color.”72 He cites the attenuated bodies and rounded joints as hallmarks of the young Costa’s style. Longhi’s own expertise in the file merely reiterates the contents of the Officina Ferrarese.73 Brief remarks by William Suida and others, including a signature by Berenson, affirm their authors’ accord with the attribution to Costa.74 In the Officina Ferrarese, Longhi cites Suida’s earlier attribution of the panels to Bramantino, noting also his former accord with this opinion.75

A final illustration of the varied, often fraught status of attribution histories is expressed by Alan Burroughs’ brief report in the object file.76 Burroughs felt that the “odd combination of primness of line and coarseness of brushwork” of the High’s panels aligned the works with Costa. A comparison with two panels in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Three Saints and a St. Lucy, is offered as justification (fig. 22).77 The attribution of the Saint Lucy panel to Costa dates back to the first publication of Berenson’s North Italian Painters of the Renaissance.78 In the pages of Longhi’s Officina Ferrarese, the panel is given to Francesco Zaganelli (1470–1532),79 the attribution that it currently bears where it hangs in storage at the Metropolitan.80 It is worth noting that in its simplicity, this isolated figure of Saint Lucy bears a resemblance to the straight-forward presentation of the saints in niches seen in the High’s panels. In addition to the Metropolitan Museum panels, Burroughs compares the Eight Saints to an Adoration of the Shepherds in the Worcester Museum (fig. 23). This painting was formally reattributed to Lorenzo Leonbruno (1477–1537) in 1996 based on the scholarship of Frances Russell.81 In its earlier attribution history, the work had been given to Francesco Francia by Wilhelm von Bode (1845–1925) and later to Costa by Evelyn Sandberg Vavalà (1888–1961).82

-

Fig. 22. Francesco Zaganelli, St. Lucy, 1500, tempera and gold on panel, 12 3/8 x 7 3/4 inches. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 30.95.292.

-

Fig. 23. Lorenzo Leonbruno, The Adoration of the Shepherds, 1510–35, tempera on panel, 14 5/8 x 101 1/16 inches. Worcester Art Museum, 1940.32.

In the face of so much uncertainty, what can be definitively said about the attributions and origins of the High Museum’s Eight Saints? An eighteenth-century guidebook description of an altarpiece in the Bolognese oratorian church of Santa Maria delle Rondini closely approximates the painting of the Virgin Enthroned with Four Saints lost with the bombing of Berlin in the Second World War. The confraternity building where the altarpiece is reputed to have stood was demolished in the early twentieth century. The strongest piece of evidence that associates the High’s panels with Santa Maria delle Rondini is Baruffaldi’s guidebook description that mentions eight small saints in rows on the sides of an altarpiece. The High Museum’s panels may have been these eight saints. However, with the impossibility of comparing them to the Berlin panel, and the fact that lateral pilasters of varied saints were a common format in the late fifteenth- and early sixteenth-century northern Italy, it is not possible to definitively connect the High’s panels to Longhi’s proposed reconstruction until further documentation is found, especially when the 1671 inventory of the confraternity of Santa Maria delle Rondini does not list any major altarpieces that correspond in subject matter to the Berlin painting.

At the nexus of the methods of connoisseurship, twentieth-century destruction, gaps in provenance, and tantalizing suggestions, it may be worth honoring the contributions of art history’s earlier approaches by labeling the works as at best “attributed to” Lorenzo Costa. Another possibility would be to further explore the Metropolitan Museum’s attribution of the Saint Lucy panel to Francesco Zaganelli as a precedent. A broader, but also more definitive designation could arise by considering the theme of the human figure’s relationship to architecture. In light of works by Costa that playfully engage with the figure’s relationship to architecture, such as St. Jerome Enthroned and the frescoes in the oratory of Saint Cecilia (fig. 24), which both involve the motif of figures displayed in niches in fictive architectural settings, it is reasonable to localize the High Museum’s Eight Saints to the context of Bologna close to the turn of the sixteenth century. With a highly successful artist like Costa exploring the motif of the figure’s relationship to architecture in prominent churches in the city, it is likely that minor workshops whose names have not passed down to us explored the concept as well. I suggest that the Eight Saints were produced in such a production context.

State of Conservation

Two primary interventions characterize the twentieth-century life of the High Museum’s Eight Saints. In 1936, the panels were cradled, cleaned, and varnished by Stephen Pichetto, the prominent conservator who worked closely with the famous London dealer Joseph Duveen.83 It was likely through Duveen that Pichetto was introduced to Samuel H. Kress. The restorer would eventually supplant Contini-Bonacossi as the collector’s primary advisor.84 Removing the Eight Saints from their mid-twentieth-century frames and viewing them from behind reveals the surprisingly substantive apparatus of the conservator’s cradle. Intending to restrict the curvature that inevitably alters wood panels that have had wet media applied to one side, twentieth-century conservators adopted the technique of affixing a lattice-work of wooden supports to the back of early Italian panel paintings. It was also customary to thin down the original panel by carving away the wood from the reverse. In many cases, it is striking how little of the original panel remains. The practice of cradling was in vogue for American collectors and conservators in light of the dramatic changes in environmental conditions that resulted when works were added to American collections.85 It was feared that in transferring the panels from cold, humid interiors of European churches and palaces to centrally heated American homes, the panels would warp and break.

Born of Italian immigrant parents in New York, the circumstances of Pichetto’s training in conservation are unknown. By the 1930s, however, the early conservation impresario oversaw a large workshop full of assistants.86 Angelo Fatta was the carpenter responsible for thinning and cradling the Kress Collection’s panel paintings. The cradles created by Fatta in Pichetto’s workshop are easily recognizable, consisting of “fixed vertical members of varnished mahogany and sliding members of clear pine, slightly waxed, each approximately 3⁄4 in. thick.”87 While the intentions behind the practice of cradling was a natural approach for preparing the objects for their new homes in American interiors, the practice of thinning the panel and applying the armature was a traumatic intervention to the historical object. For the most part, panels cradled by Angelo Fatta have remained flat with the passage of time, but in some cases new splits have occurred along the direction of the mahogany supports.88 Panels that had already warped before being cradled were flattened in a press. In these instances, there is the problem of continued paint flaking in areas where the paint was compressed in the flattening process.89

In 1957, the paintings were treated again, this time by Mario Modestini, the Roman gallerist and conservator who assumed responsibility for the Kress Collection after Pichetto’s death in 1949. In a brief reminiscence published by the Kress Foundation, Modestini relates that much of his early work in the 1950s involved addressing the side effects of the harsh treatments wrought by Pichetto.90 For the most part, paintings that entered the Kress Collection had already been cleaned by the dealers Kress purchased them from. Pichetto would only add minor corrections to the existing restorations before applying copious layers of varnish. The corrections were made with powdered pigments bound in dammar varnish.91 In addition to the practice of cradling, Pichetto relied on the even more dramatic intervention of relining, a technique in which the original support would be removed almost entirely and the remaining thin layers of paint film, ground, and supports would be applied to a new ahistorical support such as canvas or Masonite.92 Modestini interprets Pichetto’s reliance on these practices as a response to the aesthetics of the machine age.93 This view is especially apt when considering a collector such as Samuel H. Kress, a successful merchant in the everyday commodities of modern life. Even though American collectors were buying handmade, late medieval and Renaissance devotional objects, they preferred for their works to have a uniform, even surface quality.

Pichetto’s workshop applied successive layers of so-called French varnish to the newly flattened surfaces of Kress Collection paintings—alternating layers of dammar in turpentine and shellac in alcohol.94 When he retouched the paintings, Pichetto used zinc white, a material that unfortunately reacts with dammar to produce a chalky, white surface discoloration over time.95 The uniform, reflective surface quality that resulted from Pichetto’s practice is clearly seen in the High Museum’s Eight Saints. When Modestini treated the High Museum’s panels in 1957, the varnish had darkened and the white stains characteristic of Pichetto’s techniques had formed.96

Modestini’s career with the Kress Collection parallels the development of the field of conservation into a modern scientific undertaking. As he was at work on the large-scale project of conserving the art works being dispersed to the eighteen regional collections, Modestini sought a more stable alternative to the traditional materials of egg tempera, drained oils, and dammar that he had previously used for retouching and varnishing.97 A partnership with Dr. Robert Feller of Carnegie Mellon University in 1953 led to the development of a polyvinyl acetate made by the Union Carbide company.98 Known as PVA AYAB, it was supplied by an adhesives company as Palmer’s A 70.99 Modestini applied the acetate solution to paintings diluted with alcohol, thereby approximating the consistency of a varnish fit for retouching.100 It was these materials that Modestini used for the cleaning and retouching of the Eight Saints in 1957.101 As was his common technique, Modestini applied a coat of Rembradnt varnish to the newly cleaned paintings. He did his inpainting on this first layer of varnish, suspending the pigments in the PVA AYAB and alcohol mixture. Once the inpainting was done, the entire surface was unified with additional protective layers of Rembrandt varnish and wax.102

showing paint losses, St. Julian.

The paintings have not received further attention since their treatment by Modestini in 1957. In evaluations by Dianne Dwyer Modestini and Ruth Bader Cox in the 1980s and early ’90s, it was concluded that the paintings were in stable condition and no further treatment was necessary.103 As a result of Modestini’s treatments, the panels have a unified appearance to the naked eye. Early infrared photography at the High shows, however, that the paintings have suffered fairly extensive losses. There are uniform losses along the edge of the painted surfaces, suggesting that the panels were originally displayed with an engaged framing structure. The panels representing Saints Julian, Catherine, and Lucy bear the most significant losses. The last letter of Julian’s inscription was inpainted by Modestini. The cradling technique’s potential for damage is evidenced in the Saint Catherine panel by a significant split near the center of the composition. Finally, the losses along the bottom of the Saint Lucy panel are so extensive that the identifying inscription was reproduced almost in its entirety, most likely by Modestini (fig. 25). Across the eight panels, the drapery shows the clearest evidence of the original artist’s hand. Especially strong examples of the tempera technique are seen in the folds on the left hand side of the robes of Nicholas of Tolentino, the outer robe of Saint Catherine, and in Saint Sebastian’s loincloth.104

Interpretation

Despite their paint losses and Pichetto’s interventions, the Eight Saints have survived as vibrant examples of late fifteenth- to early sixteenth-century devotional painting. Though they cannot be definitively associated with the so-called Santa Maria delle Rondini altarpiece formerly in Berlin, the panels were certainly painted by a northern Italian artist close to Lorenzo Costa’s caliber, likely in the Bolognese production context, around the turn of the fifteenth century. The diminutive statues in niches painted into the fictive architecture of Saint Jerome’s throne described above, and even a series of niches with figures alongside a portal in the background of a fresco by Costa’s workshop show that the human figure enshrined in a fictive architectural setting was a salient motif in Costa’s artistic environment.

The High Museum’s panels can be used to engage museum visitors in broader formal discussions about the relationship of the human figure to framing structures and to architecture in general. Most importantly, precedents such as Giovanni Bellini’s Pesaro altarpiece establish the format of pilasters of individual saints as a standard solution for inciting lay devotion. Viewing the altarpiece from far away in the setting of a church or oratory, churchgoers and confraternity members could direct their prayers to the specific saints relevant to their concern. It is this aspect of the Eight Saints that offers the greatest potential for interpretation for museum visitors. The eight small panels offer the opportunity to experience how late fourteenth- and early fifteenth-century northern Italians practiced spiritual devotion in the context of a lay confraternity, an experience that shares commonalities with the practices of religious communities still in existence today.

Framing

To better facilitate interpretation for the public, a new framing solution is necessary. The panels’ current frames most likely date to the early 1940s, when the objects were displayed alongside other works from the Kress Collection at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC.105 I recommend following the precedent established by the National Gallery in London with the San Pietro in Vincoli altarpiece and reframing each panel individually in simple gilded, antique-style frames.106 The frames should have a simple, classicizing profile in harmony with the architecture of the niches portrayed within the panels. As Dr. Caroline Campbell of London’s National Gallery has emphasized, individually framing each panel offers greater flexibility in hanging options, allowing the display of individual panels or the entire ensemble, not to mention the fact that as they are currently displayed, there is no iconographic consistency in the pairing of the saints. Even if it is not possible to reframe the panels entirely, the saints should be rearranged in their existing frames, so that the two saints associated with travel, Julian the Hospitaller and Christopher, would be displayed together. The same should be applied for Lucy and Catherine of Alexandria, paragons of feminine virtue and Saints Nicholas of Tolentino and Vincent Ferrer as effective preachers and miracle workers. Finally, Saints Sebastian and Roche should be displayed together as healers of illness.

For a display approach that would evoke both the devotional context of a lay confraternity and the objects’ twentieth-century history as a part of the Samuel H. Kress Collection, I recommend hanging the panels in two columns on either side of another work from the Kress collection of appropriate size, such as Girolamo Romanino’s Madonna and Child with St. James Major and St. Jerome, to evoke the context of the devotional altarpiece of which they once formed a part (fig. 25).107 There is a precedent for such an arrangement in the High Museum’s current display of Carpaccio’s allegorical figures on either side of the Virgin and Child attributed to Giovanni Bellini (fig. 26).108 The present research has afforded an opportunity to further investigate a lesser-known work from the Samuel H. Kress Collection. Despite the fraught attribution history and undocumented provenance of the Eight Saints, the vibrant paintings are worth sharing with the public as a representative example of Renaissance devotional culture. They also offer the opportunity to engage the public with the history of the movement of Italian Renaissance objects to the United States via the art market in the twentieth century. An updated framing approach featuring an individual frame for each panel will enable these and many subsequent interpretations in the High Museum’s future.

—John Witty, Emory University, Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Graduate Fellowship Program in Object-Centered Curatorial Research, 2015

-

Fig. 26. Girolamo di Romano (“Il Romanino”), Madonna and Child with St. James Major and St. Jerome, ca. 1512, oil on panel, 58 5/8 x 54 1/2 inches. High Museum of Art, gift of the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, 58.45.

-

Fig. 27. Installation at High Museum of Art juxtaposing contextually related works from the Kress Collection. Photo by the author.

Selected Bibliography

Bill of Sale Memorandum. Samuel H Kress to Count Alessandro Contini Bonacossi, June 12, 1935. National Gallery of Art Archives.

Burroughs, Alan. “Lorenzo Costa, Report by Alan Burroughs.” High Museum of Art Object Files.

Cox, Ruth Barach. “Summary of the Conservation Survey of the European Easel Paintings, Miniatures, and Icons in the High Museum of Art.” June 8, 1992. High Museum of Art Object Files.

“Francesco Francia, attributed to, Adoration of the Shepherds.” Worcester Art Museum Curatorial Files.

“Notes made by Diane Dwyer during her visit to the HMA with Marilyn Perry and Mario Modestini in the mid-1980s.” High Museum of Art Object Files.

Oretti, Marcello. Le pitture nelle Chiese di Bologna. Bologna: 1767. Biblioteca Communale dell’ Archiginnasio, Manuscript 30, I.

Repertorio degl’Instromenti della Compagnia della Morte et Orazione. Confraternity of Santa Maria delle Rondini. Bologna State Archives.

“Samuel H. Kress Foundation Art Collection Data: Condition and Restoration Record, 58.38.” High Museum of Art Object Files.

Venturi, Leonello. “Expertise on High Museum’s Eight Saints.” High Museum of Art Object Files.

1671 Inventory. Confraternity of Santa Maria delle Rondini. Bologna State Archives.

Primary Sources

Baruffaldi, Girolamo. Vite de’ pittori e scultori ferraresi. Ferrara: D. Taddei, 1844–1846.

Malvasia, Cesare. Le pitture di Bologna. Edited by Andrea Emiliani. Bologna: ALFA [1686], 1969.

Secondary Sources

Allen, Josephine L., and Elizabeth E. Gardner. Concise Catalog of European Paintings in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1954.

Arslan, Edoardo. “La ‘Assunta’ del Costa a Monteveglio e la sua predella.” Rivista d’Arte (1959): 51–53.

Berenson, Bernard. The North Italian Painters of the Renaissance. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1907.

Brown, Clifford M. “Lorenzo Costa.” PhD diss., Columbia University, 1966.

Calbi, Emilia, and Daniela Scaglietti Kelescian. Marcello Oretti e il patrimonio artistico privato Bolognese: Bologna, Biblioteca comunale. MS. B. 104. Bologna: Istituto per i Beni Artistici, Culturali, Naturali della Regione Emilia-Romagna, 1984.

Drogin, David J. “Bologna’s Bentivoglio Family and its Artists: Overview of a Quattrocento Court in the Making.” In Artists at Court: Image-Making and Identity, 1300–1550. Edited by Stephen J. Campbell. Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 2004.

Filippini, Francesco. “Pittori ferraresi del Rinascimento in Bologna.” Il Comune di Bologna. Rivista Mensile XI (1933): 7–20.

Fini, Marcello. Bologna sacra: tutte le chiese in due millenni di storia. Bologna: Edizioni Pendragon, 2007.

Frizzoni, Gustavo. Zeitschrift für Bildende Kunst (1888): 299.

Gould, Cecil. National Gallery Catalogues: The Sixteenth-Century Italian Schools. London: National Gallery Publications, 1987.

Hoenigswald, Ann. “Stephen Pichetto, Conservator of the Kress Collection, 1927–1949.” In Studying and Conserving Paintings: Occasional Papers on the Samuel H. Kress Collection. London: Archetype Publications, 2006.

Krüger, Klaus. “Medium and Imagination: Aesthetic Aspects of Trecento Panel Painting.” In Italian Panel Painting of the Duecento and Trecento. Edited by Victor M. Schmidt. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2002.

Longhi, Roberto. Officina Ferrarese, seguita dagli ampliamenti 1940 e dai nuovi ampliamenti 1940–1955. Florence: Sansoni, 1956.

———. Longhi, Roberto. Piero della Francesca. Rome: Casa editrice d’arte “Vallori Plastici,” 1930.

Modestini, Diane Dwyer, with Mario Modestini. “Mario Modestini, Conservator of the Kress Collection, 1949–1961.” In Studying and Conserving Paintings: Occasional Papers on the Samuel H. Kress Collection. London: Archetype Publications, 2006.

Mostyn-Owen, William. Bibliografia di Bernard Berenson. Milan: Electa Editrice, 1955.

Negro, Emilio. Lorenzo Costa. Modena: Artioli, 2001.

Powell, Christine, and Zoë Allen. Italian Renaissance Frames at the V&A. Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann, 2010.

Previtali, Giovanni. “Roberto Longhi, Profilo Biografico.” In L’arte di scrivere sull’arte: Roberto Longhi nella cultura del nostro tempo. Edited by Giovanni Previtali. Rome: Editori Riuniti, 1982.

Réau, Louis. Iconographie de l’Art Chrétien. 3 Vols. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1959.

Roberts, Perry Lee. “Lorenzo Costa’s Montevoglio Altarpiece: A Case Study in the Representation of the Virgin’s Death and Assumption in the Late Fifteenth Century.” Arte Cristiana 85 (August 1997): 264–72.

Russel, Frances. “Another Adoration by Leonbruno.” The Burlington Magazine 124 (June 1982): 364–66.

Shapley, Fern Rusk. Paintings from the Samuel H. Kress Collection: Italian Schools, XV–XVI century. New York: Phaidon Press, 1968.

Tabbat, David. “The Eloquent Eye: Roberto Longhi and the Historical Criticism of Art.” In Roberto Longhi: Three Studies. Edited and Translated by David Tabbat. Riverdale-on-Hudson: Stanley Moss, 1995.

Varese, Ranieri. Lorenzo Costa. Milan: Silvana, 1967.

Wallace, Katherine. “Lorenzo Costa’s Concert: A Fresh Look at a Familiar Portrait.” Music in Art 33, nos. 1–2 (Spring–Fall 2008): 52–67.

Zeri, Frederico, and Elizabeth E. Gardner. Italian Paintings: A Catalogue of the Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Vol. 4, North Italian School. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1986.