Transnational Sources: Drawings and Annotations in Iba N’diaye’s High Museum Sketchbook

Margaret Nagawa

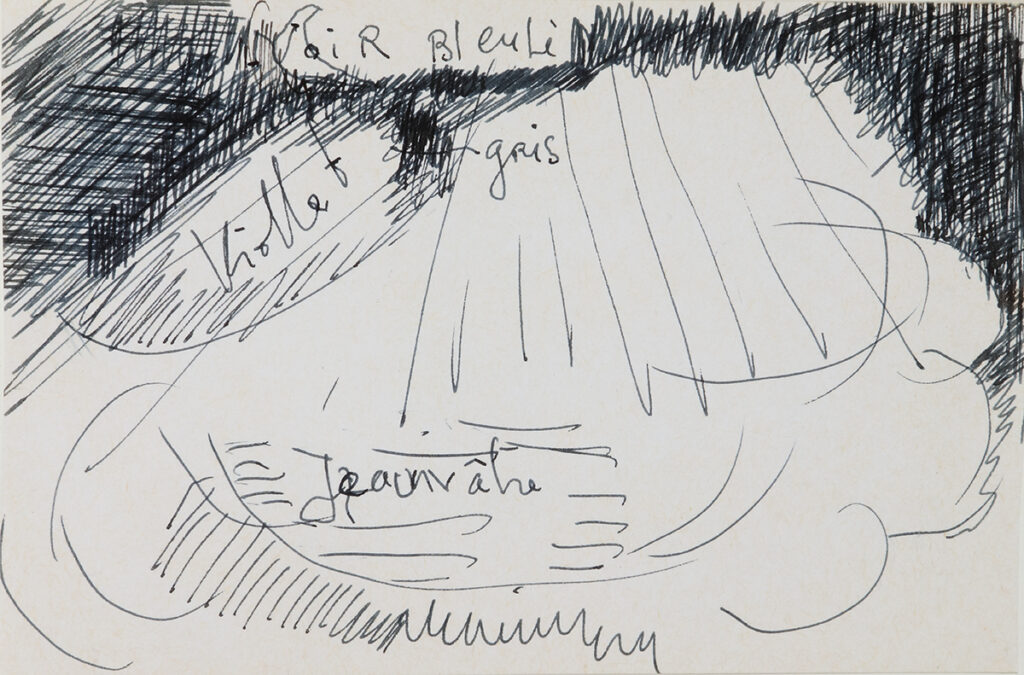

Fig. 1. Iba N’diaye (Senegalese, 1928–2008), page from Untitled Sketchbook, 1993, ink on paper, 5 3/4 x 6 3/8 inches, High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase with funds from the Friends of African Art, 2007.116. © 2023 Iba N’diaye / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Introduction

Joshua I. Cohen writes in his 2020 book The “Black Art” Renaissance that “N’diaye’s method is visible” in his sketchbooks, including an example in the High Museum of Art’s collection.1 By “method,” Cohen refers to the practice that Senegal-born, France-educated artist Iba N’diaye (1928–2008) had of drawing from models in museums in Europe and North America. Although his drawings from museum displays rarely appear directly in his paintings, N’diaye’s rapid sketching served “as a means of grasping and translating visual ideas,” Cohen argues.2 It was Okwui Enwezor and Franz-W. Kaiser’s 2002 exhibition catalogue, Vous Avez Dit “Primitif”? Iba Ndiaye: Peintre Entre Continents (Primitive, Says Who? Iba Ndiaye: Painter Between Continents), that featured two drawings from the High Museum sketchbook. One was a pen-and-black-ink drawing of a woman suckling a child, titled Maternity After an African Sculpture from Cameroun, Taken from a Sketchbook and dated 1996 (fig. 1). The second drawing was titled Greek Head After a Sculpture of the Munich Glyptothek (fig. 2). The publication provides the artist’s sources for these two drawings, information the sketchbook does not provide. N’diaye’s fascinating sketchbook (2007.116) entered the High Museum collection in 2007. Carol Thompson, then the Fred and Rita Richman Curator of African art, had acquired it directly from the artist at his studio in Paris. To date, this sketchbook remains the only work by N’diaye in the High Museum and has never been displayed in the galleries.

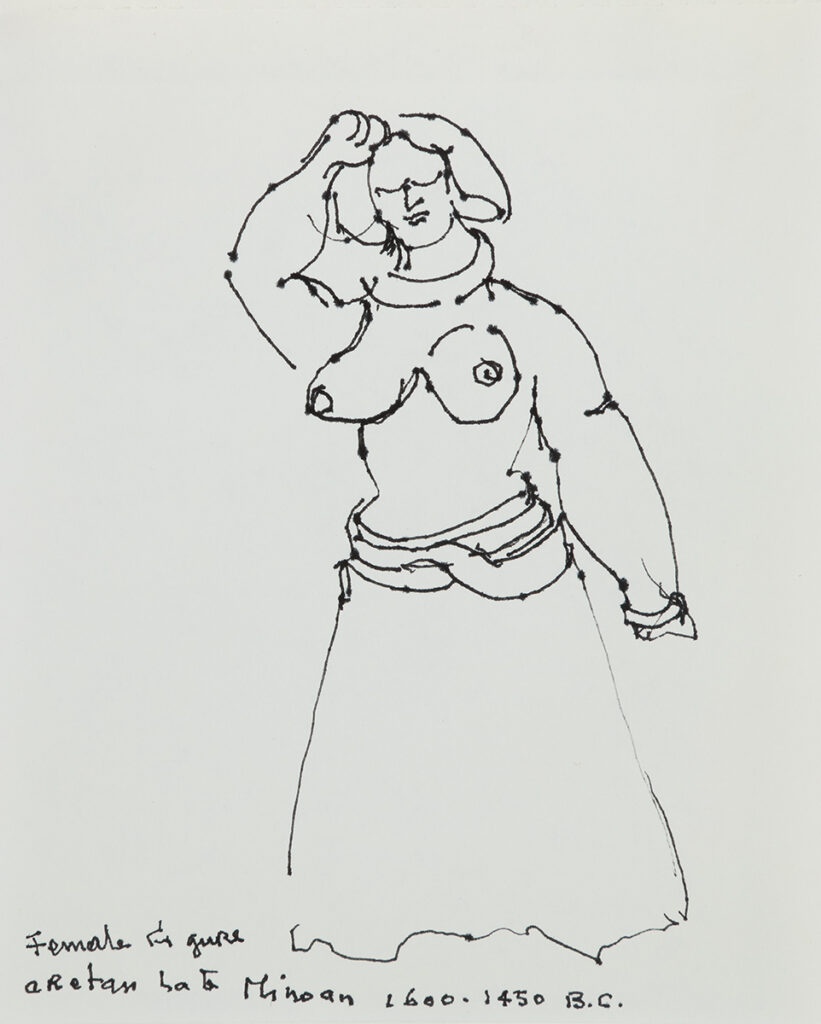

My curiosity about the High Museum sketchbook started when I saw N’diaye’s drawing of the woman and child on the Museum website. Portrayed with confident lines, the image denotes a self-assured artist’s hand. The website description also mentiones sources for N’diaye’s drawings as far different from one another as an ancient Greek Minoan sculpture and a twentieth-century Francis Bacon painting. The description prompted several questions: What else did N’diaye draw in a hundred-page sketchbook? Where did he find the sources he drew from? And how might the drawings help us understand his artmaking process? By examining the sketchbook, combined with art historical research and travel to some of the places the artist lived and worked across Senegal, the United States, and France, this research explores the transnational movement by which N’diaye studied art and made his drawings. The intention of this paper is to demonstrate N’diaye’s North American and European networks of exchange and the visual language he developed, where a museological impulse for taking annotations from museum labels and drawing from museum displays served as foundational learning activities.

I start with a discussion of some contents in his sketchbook. Next, I reflect on the condition of the sketchbook and how the physical analysis informed conservation and curatorial ideas, and end with the biography of the artist, paying attention to his words emphasizing the importance of drawing in artmaking.

The High Museum Iba N’diaye Sketchbook

Our first meeting, the sketchbook and I, was on Friday, February 25, 2022. Following museum protocol, I did not touch the sketchbook then. Only Lauren Tate Baeza, the Fred and Rita Richman Curator of African Art, handled it. I looked carefully as she turned the pages. I first touched N’diaye’s sketchbook on April 7, 2022, with Snow Fain, the paper conservator with Atlanta Art Conservation Center, in the Works on Paper Study Room. Together, we conducted a visual examination and technical analysis to assess the condition of the sketchbook and identify the artist’s materials and techniques.

N’diaye used pens and black ink on sixty-seven pages of the sketchbook, including the verso of the front cover and the recto of the back cover. He wrote annotations amounting to about ten percent of the used pages in English and French, suggesting that he was able to travel and communicate with ease in French- and English-speaking countries. He noted place names of where he made the drawings—including Washington, D.C., and New York—on the first page of his notebook (fig. 4). N’diaye also noted artists’ names—for example, that of Giovanni Bellini—and titles of works he had viewed as well as his personal responses to them. He noted the contrast between the dark background and Giovanni Emo’s richly decorated cloak in Bellini’s painting (fig. 5). Additionally, N’diaye recorded museum accession numbers (see fig. 6). He also recorded the names of the museum’s collectors and donors. This museological impulse indicates an understanding of art history and museum practices traceable to N’diaye’s art academy education in France, his few years of working at the Musée de l’Homme following his return to France in 1967, and knowledge about the work of his wife, Francine Ndiaye, an ethnologist and museum curator for several years at the Musée de l’Homme. N’diaye’s exposure to museum practices through education, work, and familial networks informed the ways in which he gathered and compiled drawings and annotations in the High Museum sketchbook.

-

Fig. 4. Iba N’diaye (Senegalese, 1928–2008), page from Untitled Sketchbook, 1993, ink on paper, 5 3/4 x 6 3/8 inches, High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase with funds from the Friends of African Art, 2007.116. © 2023 Iba N’diaye / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

-

Fig. 5. Attributed to Giovanni Bellini (Venetian, ca. 1430/1435–1516), Giovanni Emo, ca. 1475/1480, oil on panel transferred to canvas mounted on panel, 19 1/4 x 13 5/8 inches overall, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1939.1.224.

-

Fig. 6. Agnolo Bronzino (Florentine, 1503–1572), A Young Woman and Her Little Boy, ca. 1540, oil on panel, 39 3/16 x 29 15/16 inches overall, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Widener Collection, 1942.9.6.

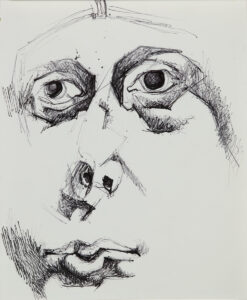

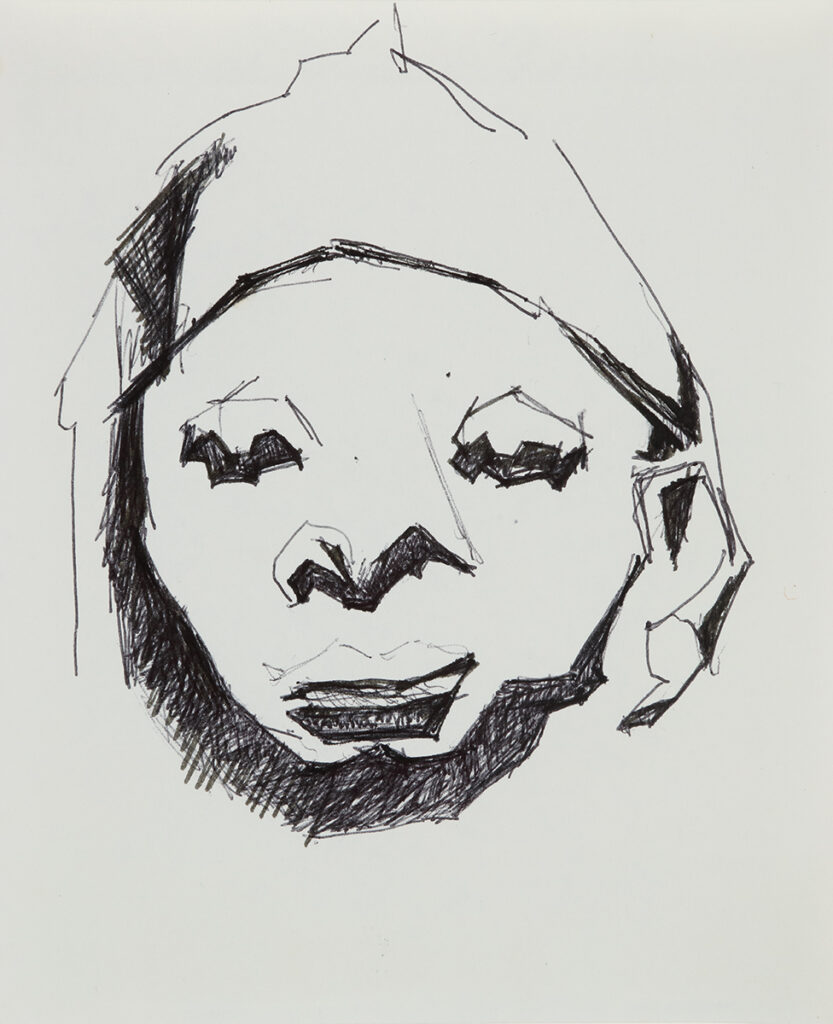

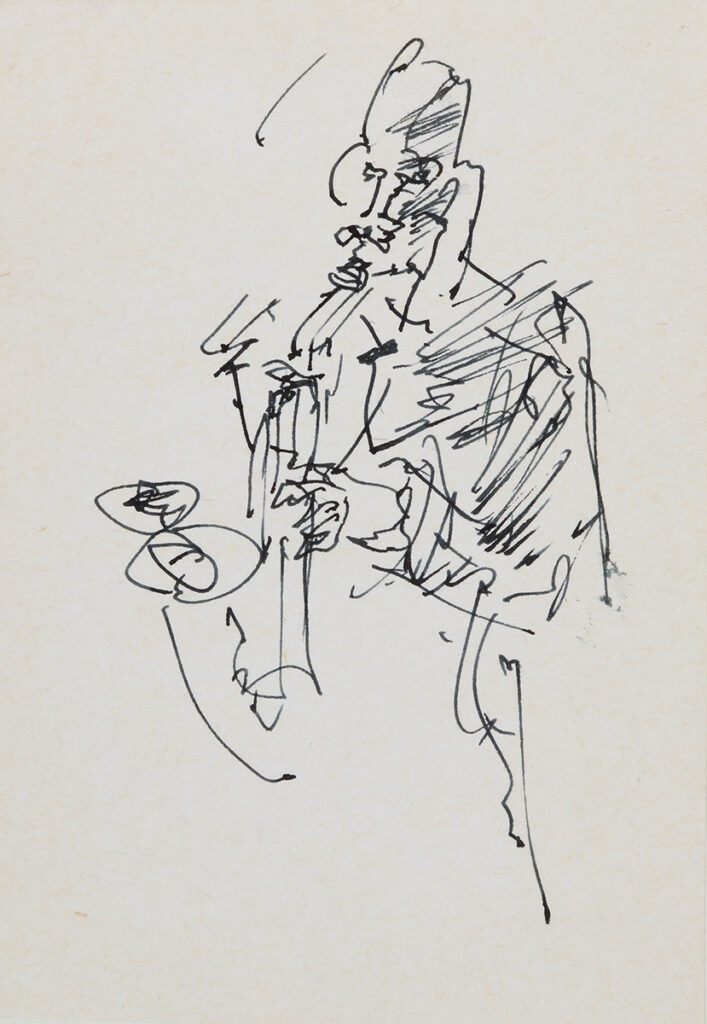

N’diaye’s drawing can be understood further as a study and practice of technique. Sidney Littlefield Kasfir (1939–2019), the esteemed Africanist art historian, characterized N’diaye as an “extraordinary master of line” in her book Contemporary African Art.3 This characteristic is borne out in the drawings executed using pen and ink in a range of line qualities, often contours (see fig. 8), suggesting the form and volume of the Minoan sculpture he studied. What’s more, N’diaye used hatching and cross-hatching (see fig. 9), building the form through modeling, where recessed areas contrast with those that are flooded with light. Further, wavy lines capture facial expressions (see fig. 10), a recurrent feature in the High Museum sketchbook. Besides a couple of composition plans (see fig. 11), the drawings portray architectural details, expressive faces, and jazz musicians (figs. 12–13). What this suggests is that the human figure, jazz, and blues remained the most recurrent themes in N’diaye’s drawings and paintings. Often, N’diaye captured parts of a represented figure or object, indicating that his purpose for studying the work did not necessitate reproducing the whole.

-

Fig. 7. Female Figurine, Crete, Late Minoan I Period, ca. 1600–1450 BCE, bronze, H. 14.1 cm; W. 6.2 cm; D. 4.1 cm, Judy and Michael Steinhardt Collection, New York. Photo courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, L. 1996.25.

-

Fig. 8. Iba N’diaye (Senegalese, 1928–2008), page from Untitled Sketchbook, 1993, ink on paper, 5 3/4 x 6 3/8 inches, High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase with funds from the Friends of African Art, 2007.116. © 2023 Iba N’diaye / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

-

Fig. 9. Iba N’diaye (Senegalese, 1928–2008), page from Untitled Sketchbook, 1993, ink on paper, 5 3/4 x 6 3/8 inches, High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase with funds from the Friends of African Art, 2007.116. © 2023 Iba N’diaye / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

-

Fig. 10. Iba N’diaye (Senegalese, 1928–2008), page from Untitled Sketchbook, 1993, ink on paper, 5 3/4 x 6 3/8 inches, High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase with funds from the Friends of African Art, 2007.116. © 2023 Iba N’diaye / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

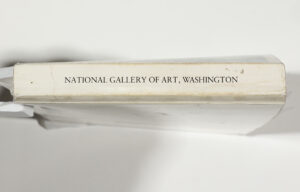

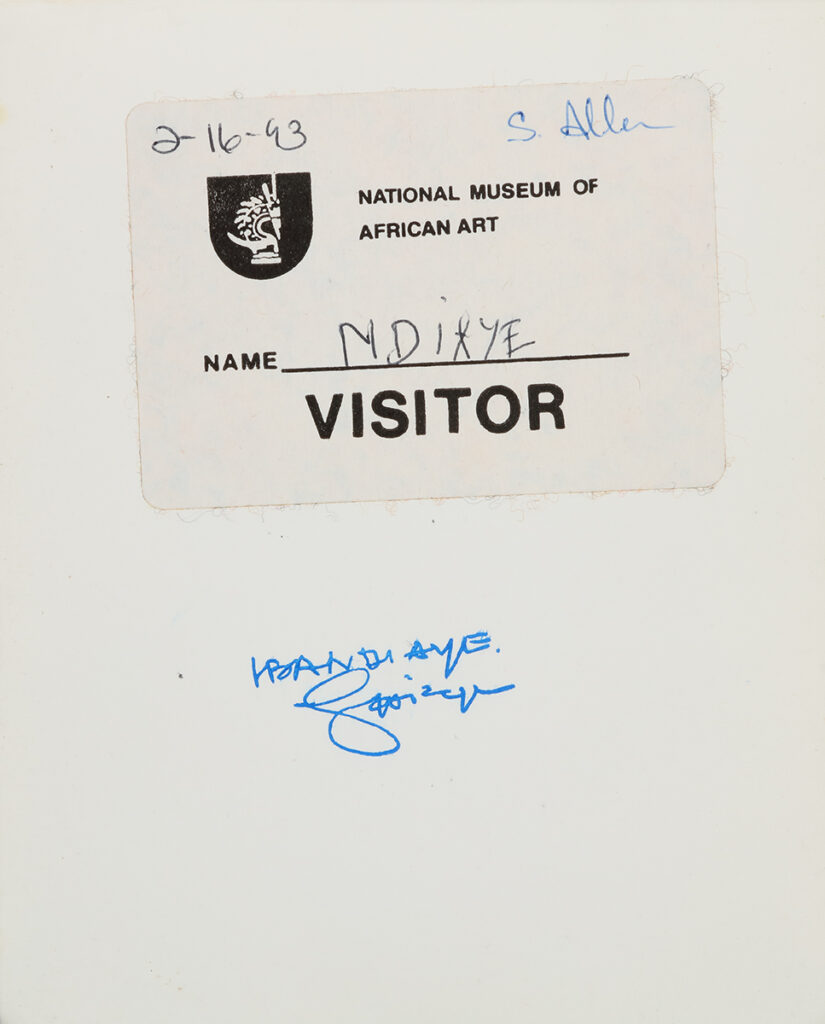

Guided by artists’ names, titles, and accession numbers that N’diaye had recorded, I was able to trace his initial travels to Washington, D.C., and New York during a trip to the Smithsonian Institution museums, including the Hirshhorn Museum and the Phillips Collection. N’diaye visited S. Allen at the National Museum of African Art on February 16, 1993 (fig. 14). He affixed his visitor sticker on the recto of the back cover of the sketchbook and proceeded to sign below the sticker, suggesting his act as a work of art. However, N’diaye bought the sketchbook four days later, on February 20, from the museum shop at the National Gallery of Art (see fig. 15). With these pieces of textual evidence, Washington, D.C., becomes integrated into the framework of N’diaye’s travels to museums.

-

Fig. 11. Iba N’diaye (Senegalese, 1928–2008), page from Untitled Sketchbook, 1993, ink on paper, 5 3/4 x 6 3/8 inches, High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase with funds from the Friends of African Art, 2007.116. © 2023 Iba N’diaye / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

-

Fig. 12. Iba N’diaye (Senegalese, 1928–2008), page from Untitled Sketchbook, 1993, ink on paper, 5 3/4 x 6 3/8 inches, High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase with funds from the Friends of African Art, 2007.116. © 2023 Iba N’diaye / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

-

Fig. 13. Iba N’diaye (Senegalese, 1928–2008), page from Untitled Sketchbook, 1993, ink on paper, 5 3/4 x 6 3/8 inches, High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase with funds from the Friends of African Art, 2007.116. © 2023 Iba N’diaye / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

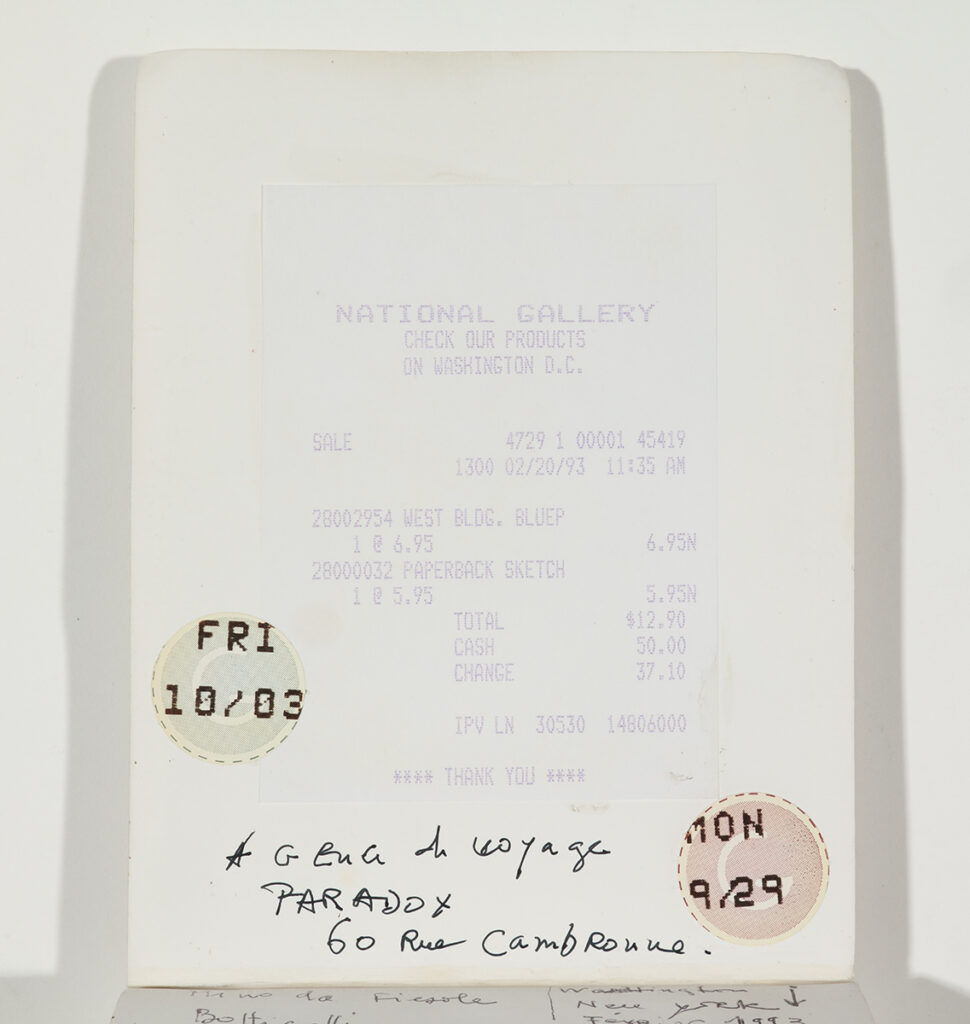

Seven months later, N’diaye likely made two visits to the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, as recorded on the two entry stickers dated September 29 and October 3 attached to the verso of the front cover together with the sketchbook purchase receipt. Furthermore, three drawings annotated with a location and date confirm N’diaye’s visit to New York on September 20, 1993 (fig. 16). These three drawings appear to have been made outside the museum. One depicts the side of a building, another a face in profile, and the third a drawing from the photograph of Edgar Degas’s face on the cover of art critic Denys Sutton’s 1986 book on Degas’s life and work. N’diaye might have made this last one while browsing the bookshelves at the Rizzoli bookstore, then located on 57th Street. With these stickers, drawings, and notes, N’diaye indicates New York as another node in his network of exchange.

-

Fig. 14. Iba N’diaye (Senegalese, 1928–2008), page from Untitled Sketchbook, 1993, ink on paper, 5 3/4 x 6 3/8 inches, High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase with funds from the Friends of African Art, 2007.116. © 2023 Iba N’diaye / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

-

Fig. 15. Iba N’diaye (Senegalese, 1928–2008), page from Untitled Sketchbook ,1993, ink on paper, 5 3/4 x 6 3/8 inches, High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase with funds from the Friends of African Art, 2007.116. © 2023 Iba N’diaye / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Regarding the dating of the High Museum sketchbook, I can confidently say that N’diaye’s start date for writing and drawing in the sketchbook was February 20, 1993. The end date remains indeterminate, but the last recorded date is April 18, 2006, on a receipt for a soft drink taken at the Dupont Café in Paris, not far from his studio in the 15th arrondissement. As a concluding act, N’diaye attached a sticker from the Museu Picasso in Barcelona on the sketchbook’s back cover, suggesting that he had visited the museum but with no indication of a date. These acts of adding stickers and noting places exceed the role of a sketchbook for gathering drawings and annotations as a learning process, indicating that N’diaye’s sketchbook also served as a journal to record his transnational travels across European countries and the United States.

-

Fig. 16. Iba N’diaye (Senegalese, 1928–2008), pages from Untitled Sketchbook, 1993, ink on paper, 5 3/4 x 6 3/8 inches each, High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase with funds from the Friends of African Art, 2007.116. © 2023 Iba N’diaye / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Conservation Concerns and Remediation

Despite the relatively good condition of the sketchbook, we observed loosening of the binding, ink bleeding from the recto to the verso of some pages, and aging paper showing moderate overall discoloration. Some collage paper elements were also aging faster than the sketchbook’s original paper. Discoloration happens due to oxidation, and conservation measures to control humidity and reduce the book’s exposure to light can slow this process. Therefore, Snow Fain, the paper conservator, secured the binding, layered each page with protective tissue paper, and constructed an archival protection box to ensure extra protection for the sketchbook in addition to the High Museum’s existing humidity and light control measures. In future studies, it would be interesting to compare this High Museum sketchbook with other sketchbooks N’diaye compiled over his lifetime to see if there are similarities in his materials, drawing techniques, and the impulse to record detailed information from museum labels.

Curatorial Options

The challenge of exhibiting a single object—a palm-size sketchbook by an individual artist, at that—is not negligible. Museum galleries tend to favor works hanging on walls or placed on pedestals. While working with the existing contemporary art or African art spaces in the High Museum, how might curators bring N’diaye’s transnational working process, evident in this sketchbook, to the attention of the museum public? I propose digitization for an online exhibition accompanied by educational materials.

We have learned the potential of online exhibitions from the recent COVID-19 lockdown, when museums digitized and made their collections available online to the public. In the case of the N’diaye sketchbook, the High Museum would make a digital reproduction of the book and develop accompanying text and sound, explaining N’diaye’s travels, drawing from museum displays and the materials he used. Such didactics would contextualize the sketchbook among N’diaye’s other drawings and paintings and those of his contemporaries. In addition, the text and sound could call attention to the works he used as sources by linking to the collecting institutions’ digitized collections, such as those of the Metropolitan Museum and the National Gallery of Art. Such digitized and linked options would allow visitors to navigate the work at their own pace and deepen collaboration networks between museums.

An additional onsite educational component might include providing paper and pencils and a docent to lead student visitors and family groups in drawing activities in the museum galleries. These docent-led sessions would provide an opportunity to talk about paper conservation with museum visitors and share insights into evolving technological possibilities for exhibitions. This suggestion aims to create a space for viewing the digitized sketchbook and encourage dialogue about the transnational character of a modern artist’s artmaking and the central role museums played in N’diaye’s practice. As a result, the sketchbook would benefit from less physical handling, and scholars of modern African art in a global context would have easier access to N’diaye’s work.

Why We Should Care About N’diaye’s Sketchbook

This sketchbook gives us concrete evidence of how N’diaye made his drawings, the kind of work he found meaningful, and where he traveled to find his sources when visiting museums in Europe and the United States, watching people at cafés, and browsing in bookstores. This kind of information enriches our understanding of N’diaye’s circulation in what Joseph L. Underwood termed “node[s] on a complex network of exchange” in his 2020 chapter “Parisian Echoes: Iba N’diaye and African Modernisms.” Underwood examines N’diaye’s lived experiences within a network of African modernists and the technical approaches in artmaking he practiced and taught between Paris and Dakar in the mid-twentieth century. The High Museum sketchbook adds a later period of the artist’s life and movements that include Barcelona; Washington, D.C.; and New York as additional nodes of interaction.

An additional reason why N’diaye’s sketchbook matters is that the continuity between his drawing from discernible sources is especially noticeable in his 1986 painting Juan de Pareja Menaced by Dogs (After Velázquez) (fig. 17). In this painting, N’diaye engages in a heated dialogue with Diego Velázquez’s Juan de Pareja (1606–1670) of 1650 (fig. 18), introducing threatening dogs on the right side of the composition with an enslaved Black man’s portrait. N’diaye highlights the perilous life the man might have lived in seventeenth-century Rome. His rendition discards Velázquez’s detailed lace collar, replacing it with a single brushstroke of white paint. The edges of Juan de Pareja’s hair blend into the background, introducing an indeterminacy about where the figure ends and the background begins. The canvas shows an energetic red underpainting. The warm red accentuates the black and white in the man’s eyes, echoing the dogs’ eyes in an atmosphere of unrelenting looking, likely undesirable to the represented man. Enwezor characterizes these eyes as “orbs of light that stand for eyes.”4 In this painting, as one might observe in most of his drawings, N’diaye has selected one feature from Velázquez’s work to emphasize: the eyes. When he visited museums, N’diaye was learning from art history, but he was also making thoughtful selections of the qualities he wanted to study.

-

Fig. 17. Iba N’diaye (Senegalese, 1928–2008), Juan de Pareja agressé par des chiens (Juan de Pareja Menaced by Dogs) (after Velázquez), 1982, oil on canvas, 63 3/4 by 51 1/8 inches, private collection. Photo courtesy of Sotheby’s.

-

Fig. 18. Velázquez (Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez) (Spanish, 1599–1660), Juan de Pareja (ca. 1608–1670), 1650, oil on canvas, 32 x 27 1/2 inches, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, purchase, Fletcher and Rogers Funds, and Bequest of Miss Adelaide Milton de Groot (1876–1967), by exchange, supplemented by gifts from friends of the Museum, 1971, 1971.86.

Similar techniques of selection are observable in N’diaye’s paintings of jazz musicians, although some represented figures and musical instruments are not readily apparent. In Trio of 1999 (fig. 19), which N’diaye made during the time he was compiling the High Museum sketchbook, the singer’s figure is readily perceptible. Head tilted to the side, her wide smile and downcast eyes express a deeply felt joy, suffused in the dark orange hue connecting this ecstatic face to the saxophone or trombone next to her head. N’diaye depicts the woman with shoulders sensually bared, arms adorned with white bangles that echo the stripes in her strapless white top. N’diaye paints layers of lines on both sides of the singer and sets her against a dark, shallow background, leaving the viewer to guess at the other figures making up the trio of performers.

-

Fig. 19. Iba N’diaye (Senegalese, 1928–2008), Trio, 1999, oil on canvas.

-

Fig. 20. Iba N’diaye (Senegalese, 1928–2008), Hommage à Bessie Smith (Homage to Bessie Smith), 1987, oil on canvas, 52 1/16 × 77 5/8 inches, Smithsonian National Museum of African Art, Washington, DC, gift of Mme Diouf and museum purchase, 2002-13-1. © 1987 Iba N’diaye / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

N’diaye also makes conceptual links between the arts. In Hommage à Bessie Smith (Homage to Bessie Smith) of 1987 (fig. 20), N’diaye links the improvisation of jazz with his painted layers of lines and fields of color. At least eight figures populate the shallow, blue-gray background, their faces bearing suggested features in what Underwood describes as “gestural brushstrokes,” inviting the viewer’s eyes to fill in the missing lines.5 Three brass instrument players in dark suits share the foreground space with a wide-open-mouthed singer dressed in red, presumably Bessie Smith (1894–1937), the renowned jazz singer born in Chattanooga, Tennessee. N’diaye must have experienced pulsating covers of her music in Harlem and Paris jazz clubs, for the painting he makes in her honor possesses a layered complexity that gives visual voice to the lead singer in the bright red garment and the only open mouth among the figures represented. N’diaye experienced jazz music unmediated by the museum institution and the language of museum labels. So, although his drawings of jazz musicians in the High Museum sketchbook bear no inscriptions, they nonetheless capture another dimension of his movement among museums and social spaces. The interviews he gave during his lifetime further guide our understanding of the importance of travel and drawing for his art practice.

Iba N’diaye’s Biography

N’diaye was born in 1928 in Saint-Louis, a port city on the Atlantic coast of Senegal. As a teenager, he made comic strips and painted film posters for the city’s popular Cinema Vox to advertise screenings of American, French, and Senegalese films.6 Beginning in 1948, he studied art and architecture at the École des Beaux-Arts in Montpellier and Paris before joining the Académie de la Grande Chaumière in Paris. Within a ten-year period, N’diaye had worked in the ateliers of the architect Georges-Henri Pingusson (1894–1978), the painter Yves Brayer (1907–1990), and the sculptor Ossip Zadkine (1890–1967). Zadkine’s formative years as an artist coincided with the burgeoning ethnographic and art market interest in African sculpture in Europe, inspiring works such as Venus (1920–1924) in the Tate collection.7 Notably, Zadkine studied museum objects at the Louvre and encouraged N’diaye to visit France’s large collections of art from its colonies displayed in Paris museums, such as the Musée de l’Homme. So began N’diaye’s frequent visits to museums that would continue throughout his career.

N’diaye returned to Senegal in 1958 and set up a studio in Dakar during the lead-up to the country’s gaining independence from France. The newly elected president, Léopold Sédar Senghor, invited N’diaye to direct the Section Arts Plastiques, or the fine arts department, at the newly founded École des Arts du Sénégal in Dakar in 1960. Scholars have located N’diaye’s art in opposition to the Négritude movement, a literary and philosophical undertaking started by a few Black students from the French colonies who met in Paris in the 1930s.8 While in Paris, these students found themselves isolated and treated as inferior despite their French citizenship. Aimé Césaire from Martinique, Léon-Gontran Damas from French Guiana, and Senghor responded by conceiving a philosophy to contest French domination and revive African cultural heritage so that Black people around the world might regain pride in themselves and their histories. However, during the euphoric 1960s, when many countries in Africa attained independence, N’diaye did not follow the Négritute ideas of reclaiming African art or his colleague Papa Ibra Tall in rejecting some aspects of his French education to retrieve Africa’s pre-colonial heritage.9 Instead, N’diaye had “a healthy skepticism about the advocacy of a uniquely African aesthetic,” as Ima Ebong asserts, and he continued to study, draw, and paint using techniques he had acquired in French art academies and praising the accomplishments of artists anywhere in the world.10 In 1987, N’diaye reflected, “Africa is an immense continent whose peoples and cultures I am far from knowing.… As for the formal relationship which may exist between my art and the visual arts of the African continent, I didn’t research them in a systematic manner. I studied African sculpture just as I did Roman and Gothic and European sculpture: by drawing it when I saw it in the museums.”11 N’diaye’s statement suggests that the artist relied upon multiple sources from different cultures by directly observing art displayed in museums. However, because few countries in Africa possess Roman or Gothic art, his statement indicates a complex geography encompassing multiple locations within and beyond the continent.

While in Dakar, N’diaye appears to have modeled his department on his own education, emphasizing art history and drawing.12 Notably, he urged his students to familiarize themselves with art from cultures around the world. Reflecting on his teaching in a 2002 interview with Franz-W. Kaiser, N’diaye said, “While I was teaching, I introduced an art history course using slides, so that the students could become familiar with artists from all over the world—including those who were profoundly influenced by African art—and their techniques and artistic careers. In my opinion, this was an indispensable step in educating the eye.”13 Alongside sustained looking, N’diaye encouraged his students to draw from reproductions of European and African art “in educating the eye.” In a photograph of him instructing a student at the École des Arts du Sénégal, N’diaye points at the student’s drawing from a plaster reproduction of the Hellenistic Greek statue of Venus de Milo sitting on a shelf beside a nineteenth- or twentieth-century wooden Kpeliye’e mask, possibly made by peoples classified as Senufo in northern Côte d’Ivoire.14 In this instance, N’diaye expected his student to train by drawing from both European and African sculptural traditions.

Other artists and scholars have discussed the problems and merits associated with the belief that drawing educates the eye. Ernst Gombrich (1909–2001), an art historian of the twentieth century, describes in his 1960 book Art and Illusion a historicized stylistic change that distinguishes between the way one sees and how one represents what one sees. He warns that “it is dangerous to confuse the way a figure is drawn with the way it is seen.”15 Deanna Petherbridge, an artist and writer specializing in drawing, explicates in her 2008 essay “Nailing the Liminal: The Difficulties of Defining Drawing” that “the correlation between the act of drawing and training the eye is a significant aspect of drawing which has dominated much subsequent art school teaching, in the West and globally, and which remains one of the few notions about drawing generally regarded today as ‘irrefutable.’”16 Although Petherbridge outlines this position, she also highlights the prevalence of “deliberately deskilled” drawing among twenty-first-century students. N’diaye believed, taught, and practiced the art of drawing from a range of sources to train the eye. To demonstrate the importance he attached to drawing, his April 1962 exhibition at the École des Arts showed twelve paintings and ten drawings of the human figure, including a drawing simply titled Anna (1962).17

In 1967, N’diaye and his wife permanently relocated to France. In subsequent years, N’diaye participated in the First Salon of Senegalese artists at the Musée Dynamique de Dakar (1973), held a solo show at the Chiwara Gallery in Atlanta (1980), and exhibited another at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (1981) curated by Lowery Stokes-Sims.

Provisional Conclusions

Many questions remain unanswered regarding the sources and locations of N’diaye’s High Museum sketchbook. In 2013, N’diaye’s estate donated 154 works to his country of birth, Senegal. My advisor, Dr. Susan Elizabeth Gagliardi, and I traveled to Senegal and France to locate comparative examples of his sketchbooks. We also aimed to visit the places N’diaye had lived, worked, and studied to try and trace his lived experiences and understand the conditions that shaped him as a person and an artist. The structure of Cinema Vox in Saint-Louis still stands; however, with a dilapidated roof and interior, the building no longer functions as a cinema hall. Nonetheless, its location along the waterfront suggests a leisurely atmosphere and a rich cultural life during its active time. Florence Alexis curated N’diaye’s retrospective, titled The Work of Modernity, as part of the 2008 Dak’Art Biennale. The biennale institution remains vibrant, and its archives will furnish scholars with research resources. Concerted efforts of Collection Jom in Dakar ensure that works by Senegal’s eminent artists return to the country and are available for research purposes. Unfortunately, N’diaye’s house in Paris was demolished; however, the Dupont Café, where he made the drawing on the back of a receipt dated 2006 in the High Museum sketchbook, still stands on the bustling corner across the road from the Convention Metro stop. Back in the United States, I visited the National Museum of African Art in Washington, D.C., to examine the wooden sculpture (fig. 21) by an unrecorded Kongo artist in the present-day Democratic Republic of Congo, attributed as a source for N’diaye’s Maternity drawing. The woman in the sculpture is not suckling a child; rather, the child places its right hand on the outside of the mother’s breast. If this sculpture served as N’diaye’s source, it demonstrates the artist innovating a close and tender familial relationship. In this instance, what N’diaye saw might not have translated directly into what he drew. In these pages, I hope to have demonstrated that examining an artist’s drawings and annotations, such as those in N’diaye’s High Museum sketchbook, provides information about the artist’s materials, movements, and techniques that might otherwise remain obscure if one looks at finished works alone.

Selected Bibliography

Cohen, Joshua I. The “Black Art” Renaissance: African Sculpture and Modernism across Continents. Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2020.

Ebong, Ima. “Negritude: Between Mask and Flag,” in Ed. Susan Vogel, Africa Explores: 20th Century African Art, 198–209. New York: The Center for African Art, 1991.

Enwezor, Okwui, and Franz-W. Kaiser, Iba Ndiaye: Peintre Entre Continents: Vous Avez Dit “Primitif”? = Painter between Continents: Primitive, Says Who? Paris: Adam Biro, 2002.

Gombrich, Ernst. Art and Illusion: A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation. New York: Pantheon Books, 1960.

Grabski, Joanna. “Painting Fictions/Painting History: Modernist Pioneers at Senegal’s Ecole des Arts.” African Arts 39, no. 1 (2006): 38–94.

Harney, Elizabeth. “The Densities of Modernism.” The South Atlantic Quarterly 109, no. 3 (2010): 475–503.

Kasfir, Sidney Littlefield. Contemporary African Art. London: Thames & Hudson, 2020.

Petherbridge, Deanna. “Nailing the Liminal: The Difficulties of Defining Drawing.” In Ed. Steve Garner, Writing on Drawing: Essays on Drawing Practice and Research, 27–41. Bristol and Chicago: Intellect Ltd, 2008.

Strong, Peter. “Ossip Zadkine,” in Jewish Quarterly, 4:1 (1956): 26–27.

Underwood, Joseph L. “Parisian Echoes: Iba N’Diaye and African Modernisms.” In Arrival Cities, 159–176. Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2020.

Underwood, Joseph L. “Iba N’Diaye,” in African Artists: From 1882 to Now, Eds. Phaidon editors. New York, NY: Phaidon Press, 2021.

Vogel, Susan, Ed. Perspectives: Angles on African Art, New York: The Center for African Art and Harry N. Abrams Inc. New York, 1987.