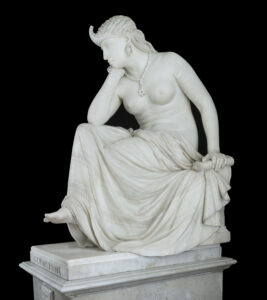

Fig. 1. William Wetmore Story (American, 1819–1895), Hero Looking for Leander, 1858, marble, 70 x 21 x 21 inches. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, gift of the West Foundation in honor of Gudmund Vigtel and Michael E. Shapiro, 2010.93. Photo by Almont Green.

William Wetmore Story wrote in his Conversations in a Studio (1890) that “in art … as much as in law, it seems to me that culture and a large education are almost necessary to create a great artist.”1 Story himself was perhaps the best embodiment of this sentiment. He was born February 12, 1819, the second son and sixth child of Supreme Court Judge Joseph Story and Sarah Waldo Wetmore. Although he is best known for his sculptural works, Story was also a noted poet, author, intellectual, playwright, and lawyer, having begun his adult life as a graduate from Harvard Law School. By 1845, he had already modeled a portrait bust of his father; it was so well received that Judge Story himself sent it to be displayed at Harvard. It is perhaps no surprise then that William Wetmore Story won the commission for his father’s memorial statue at Mount Auburn Cemetery. In preparation for the memorial, Story spent two years in Europe cultivating his tastes, which ultimately cemented his desire to pursue a career as an artist. Story moved himself and his family permanently to Rome in 1850.

Description

Hero Looking for Leander (fig. 1) is not only the earliest of Story’s sculptures in the High’s collection but also one of the most unassuming; the female figure’s slim frame, timid nature, and youthful features are distinctly at odds with the artist’s other female power-houses, such as Medea (fig. 2). The statue is based on the classical myth of Hero, an innocent young priestess of Aphrodite at her temple in Sestos, who falls in love with a dashing young man named Leander from across the Hellespont. Leander convinces her that Aphrodite would much rather she abandon her vows of chastity in the face of what is obviously true love, and swims across the Hellespont each night guided by the light of a torch she holds aloft in her tower. A winter storm claims his life, however, and the sight of his drowned body leads Hero to cast herself into the sea and join her lover in death.

The statue, which stands on a short circular base, is roughly life-size and made of a fine-grained white marble with slight grey veining. The base has been smoothed around the edges but left rough on the top to simulate sand, an illusion further supported by two seashells. Hero holds a torch aloft in her right hand and clutches the folds of her himation and chiton with her left, which have fallen away to reveal her right breast.

The motion of the statue changes depending on the viewer’s perspective. From the right side, Hero seems to hunch forward, leaning into the light of her torch but still remaining stationary. The diagonal line of her hairstyle matches that of the torch, leading the viewer’s eye in the same direction as her own. As one moves counter-clockwise toward the front, her eyes are blocked, and the focus is at once switched to her disheveled state, the raised arm, garment folds, and extended left foot acting almost as a frame. A head-on perspective reveals her full facial expression, knitted brows and wide, staring eyes drawing the viewer into her distress. Seen from the left and back, however, Hero takes on a distinctly awkward pose, with a strong diagonal formed by the recessed back leg and extended right arm. Whether this is due to an unintended viewing angle or simply a lack of experience on Story’s part—as he had not yet fully formulated his canon of proportions—is unclear.

Provenance

We know from a letter to Enrico Nencioni, an Italian poet and literary critic, that Story had conceived of the idea and embarked on modeling Hero after his return to Rome in 1856.2 The Cosmopolitan Art Journal further informs us that the full-scale model was completed by March of 1857, while Nathaniel Hawthorne remarks that it was in the process of being transferred into marble during his visit to the studio on February 12, 1858.3 The statue was finished by November of that same year.4 It was met with rave reviews and even had a potential buyer by January 1859 (one Colonel Greene, who promised to purchase it, along with a painting by one of Story’s close friends, provided that his new rifle patent did well).5 Unfortunately, a review by the London Spectator in 1863 detailing Story’s recent works lists Hero as a resident in the studio.6 The statue was eventually acquired by a William Douglas of New York, before ending up at the Old Post Road Gallery in Larchmont, New York, sometime during the 1970s or ’80s, after which Hero made her way into the West Foundation collection and thence to the High Museum.

Reception

Despite the lack of patrons or commissioned copies, Hero Looking for Leander was quite well received by Story’s contemporaries. Hawthorne was among the first to see the statue in progress and wrote in his journal that “in the outer room of his studio a stone-cutter, or whatever this kind of artisan is called, was at work, transferring the statue of Hero from the plaster-cast into marble; and already, though still in some respects a block of stone, there was a wonderful degree of expression in the face.”7 One critic, Atelier, writing for the Cosmopolitan Art Journal in June of 1857, was a bit more reserved in his praise, saying that it was a “very promising, finely conceived work. It certainly shows with what success he has applied himself to the study of antiques.” While Atelier reserved his praise for more established artists such as Harriet Hosmer and Thomas Crawford, he noted that Story was “yet comparatively young and may do much for the art-taste of his country.”8

Atelier may have had a valid point when criticizing the “art-taste” of America, as many of the American visitors to Story’s studio came across as remarkably uncultured. The artist kept a list of humorous anecdotes from these visits, and his circle of friends took note of them as well. Hawthorne, for example, notes that a certain American “remarked of a statue of Hero, who is seeking Leander by torchlight, and in momentary expectation of finding his drowned body, ‘Is not the face a little sad?’”9

In 1860, the Dublin University Magazine printed a glowing article on Story, highlighting his many fine works and excellent character. The article, titled “American Imaginings,” was reprinted that July in Dwight’s Journal of Music for the benefit of Story’s friends and family in Boston. The author praised Cleopatra (fig. 3) first and foremost in order to, as the author says, provide an excuse for “entering her modeler’s studio, thence to illustrate and enlarge our remarks upon the strange promise which the training of American realism is making to the ideal.” He first provides a laudatory description of Story’s Red Riding Hood, and “then there is Hero, still in girlish form, lifting a torch, which shows an agony in the sweet eyes of the watcher, whose dainty naked feet are set upon the sand of that cruel Hellespont.”10 Here she takes her place in a timeline of Story’s genius, leading up to the artistic glory of Cleopatra.

Although still a resident in the studio, Hero was not without admirers. In January of 1863, the London Spectator raved that “a smaller statue of Hero looking for Leander, torch in hand, is almost faultless in its representation of anxious doubtful search” and predicted that “the timid, beautiful girl, overmastered for the moment by one sentiment, will probably reappear in a hundred imitations, and become a household form.”11 Unfortunately, Hero was not destined for this fate and does not seem to have ever gained the widespread fame the London Spectator thought was due her.

Inspiration and Influence

The story of Hero and Leander was most fully recorded by Musaeus Grammaticus in the early sixth century CE. It had, however, been treated much earlier by Ovid in the Heroides and was mentioned by both Martial and Virgil. It would go on to be adapted by Christopher Marlowe in 1598, Keats in 1817, and perhaps most importantly, by Leigh Hunt in 1819—all of whom Story was either familiar with or, in the case of Hunt, close friends.12

Ovid’s Heroides, or Letters from Heroines, comprises emotionally fraught missives from famous women of mythology to their lovers. Both Hero and Leander have letters to each other in the Double Heroides, conceived of as having been written during a particularly nasty storm when Leander was unable to make his nightly journey across the Hellespont.13 Leander’s letter consists of reassurances to Hero that it is only the storm that keeps him from her, while Hero herself cannot seem to decide between anger at his absence and her own inability to go to him, fear for his safety, and grief at his absence. Although she ends with an admonition to be cautious and arrive safely, the psychological trauma she exhibits in her letter is likely indicative of her fate.

Despite Ovid’s chronological precedence, Musaeus is still the best-known ancient source for the story of the doomed young couple. His poem represents the most complete version of the story that we have, although references by authors such as Virgil and Ovid make it clear that it was present in popular culture long before then. George Chapman published one of the earliest English editions in 1616.14 Other notable editions were put forth in 1810, 1825, and 1874, fueling the popularity the story found in the periods both immediately preceding and following Story’s execution of Hero. Musaeus does not differ substantially from Ovid, except in his focus on Leander’s journey through the Hellespont. Hero’s distress, while the dominant theme in Story’s Hero, is nonetheless relegated to a few lines at the end of Musaeus’ poem:

Full o’er the Deep impatient Hero por’d,

Pond’ring the long delay; peace from her thoughts,

And soft repose are banish’d, cares on cares

Distract her lab’ring bosom; soon as Dawn

Wakes from his throne of light, around she throws

The gaze of anxious hope….15

Her death comes soon after, when she flings herself from the top of her tower to land on Leander’s corpse far below. While Ovid does not mention the ultimate fate of the two lovers, Musaeus’ account of the tragedy became canon for later versions, one of which was penned by Marlowe.

Story was an admitted fan of Marlowe and wrote that he was, “in my opinion, the greatest of all the old dramatists after Shakespeare himself.”16 He quotes the playwright and poet extensively in Conversations and considered him an influence on Shakespeare. Marlowe was born in Canterbury in 1564 and went on to become a popular tragedian before his early death in 1593. Hero and Leander was an unfinished work published in 1598, wherein Hero, a young priestess as fair as Venus herself, falls for the young Leander. Marlowe’s writing concludes with their first consummation and ends rather abruptly, with Hero standing naked and somewhat abashed before Leander. George Chapman finished the story later that year, with Hero’s sacrifice to Venus being rudely denied and Leander’s tragic death at sea. The moment depicted in Story’s statue, where Hero is searching for Leander and does not yet know his fate, plays a small part in Marlowe and Chapman’s work. Their focus, rather, is on Leander’s beauty, Hero’s battle between her desire for him and the guilt she feels over betraying her vows of chastity, and the injustice of their fate. As opposed to Marlowe, who held a scholarly fascination for Story, Leigh Hunt was both an inspiration and a personal friend. The two met in the summer of 1850 through an introduction by Thomas Carlyle, a prominent Scottish historian and social commentator. They became fast friends, with Story avowing his visits with Hunt as among his “pleasantest memories of England” and Hunt expressing his admiration for Story’s poetry, sculpture, and company.17 Story was undoubtedly familiar with Leigh Hunt’s version of Hero and Leander, not only through his friendship with the man but through his role as intermediary with the Boston publishing firm Ticknor and Fields. While Hunt’s works were available in America before this, Hunt himself had never seen a penny from their sale as none of the versions were officially endorsed. Story’s efforts on his behalf would see the first complete, approved version of Hunt’s poetry available in America.

Hunt first published his Hero and Leander in 1819; it was reprinted and somewhat shortened between 1832 and 1860. Whereas Marlowe was preoccupied with Hero’s psychological distress over the breaking of her vows and the reaction of the gods to the young priestess and her lover, Hunt focuses instead on the interactions between the two and the respective moments when Hero and Leander realize their fate. Story may have been especially struck by the following lines describing Hero’s distress:

I need not tell how Hero, when her light

Would burn no longer, passed that dreadful night;

How she exclaimed, and wept, and could not sit

One instant in one place; nor how she lit

The torch a hundred times, and when she found

’Twas all in vain, her gentle head turned round

Almost with rage; and in her fond despair

She tried to call him through the deafening air.18

Although Hunt places Hero in her tower with a torch that will not stay lit in the stormy weather, the psychological distress evident in the passage mirrors that in Story’s creation.

The tale of Hero and Leander also inspired a number of musical and dramatic adaptations, which—while not usually a direct inspiration for sculptural works—must be considered in this case; Story was not only a talented vocalist and playwright himself, often putting on shows in his suite of apartments in the Palazzo Barberini, but a great fan of the opera and was reported to listen to music in order to get into the right mindset for working in his studio. References to Hero and Leander occur in about seven of Shakespeare’s plays, and their story was adapted musically by Handel in 1707, Scarlatti in 1725, Schumann in 1837 (In der Nacht), and Liszt in 1853 (Ballade No. 2 in B minor, S. 171).

There are no surviving representations of the Hero and Leander myth from ancient Greece or Rome (except for a possible representation from Pompeii of Leander swimming, which Story may or may not have been familiar with), but there was certainly a plethora of early modern and contemporary works for him to be inspired by. Most of these depicted Leander’s nightly journey across the Hellespont, as in Carracci’s seventeenth-century representation from the Palazzo Farnese in Rome. The rondel, part of a larger series, shows Leander swimming the Hellespont in the foreground, while Hero leans out over the top of her tower with blazing torch in hand. Others chose the climax of the story when Hero discovers Leander’s corpse, as in Domenico Fetti’s Hero Mourning the Dead Leander (1621–1622) from the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. Fetti may have been inspired by Marlowe’s tale himself, as Leander’s lifeless corpse is grieved by Eros and a collection of Naiads in the foreground, with only a lone Triton gesturing to Hero as she throws herself from her tower in the background.

Jean-Joseph Taillasson’s 1789 painting from the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Bordeaux bears the most physical resemblance to Story’s work in that Hero is not only an important character in the composition (both through her position in the foreground and the bright colors of her clothes, which are in stark contrast to the muted greys and browns of the sea and shoreline) but also appears on the shoreline with her right breast bared in similar fashion. In fact, Story’s version is somewhat remarkable for not overtly depicting Leander in any way; rather, he chooses the moment right before that discovery, when Hero fears the worst but still has hope for Leander’s safe arrival. It is precisely this psychological tension, or “pregnant moment”—known to be popular in ancient Roman art since Gotthold Ephraim Lessing’s 1776 essay on Laocoön, but more recently explored by Bettina Bergmann in the context of Pompeian wall paintings—that would come to be a hallmark of Story’s most successful creations (see figs. 4, 5).

Psychological drama might have been enough for some artists, but William Wetmore Story also had to satisfy his need for historical accuracy. The lack of ancient prototypes did not deter him in the least, and his study of ancient customs can be seen in the tightly bound fillet on his figure’s head (often worn by Greek women during rituals) as well as the differing layers and textures between her chiton and himation, in addition to the weights on the latter. He seems to have used the Ludovisi collection, currently housed in the Palazzo Altemps in Rome, as inspiration for various elements in this sculpture. The Torchbearer, restored in the seventeenth century by sculptor Alessandro Algardi, resembles Hero not only in the composition of the torch (a bundle of wrapped rods common in ancient Greek and Roman depictions) but also the torch-bearing arm and the advanced right leg. Likewise, the hairstyle is similar to the Juno Ludovisi, with the hair swept back over the ears and tied in a low bun, with curled locks escaping down the side of the neck. These distinctive tendrils of hair, known as Aphrodite locks for their prevalence in ancient statues of the goddess, would have been appropriate for one of her priestesses and were undoubtedly a conscious choice on Story’s part.

Story’s Hero, however, is not merely an academic exercise in historical reference; rather, it is a highly original and psychologically charged composition. Hero’s disheveled state of dress is also telling, as it speaks both to her mental anguish and the loss of her chastity.19 It should be noted that this was never meant to be an erotic work; Story was firmly against nudity in art simply for the sake of carnal enjoyment, and its inclusion here is significant as it signals to the discerning viewer Hero’s psychological distress and anxiety over the fate of her beloved. In addition, and perhaps more significantly, all of the literary accounts emphasize how she cast aside her vows of chastity at Leander’s behest, whether Aphrodite would have approved or no, and her bared breast reminds the viewer that this is not a woman to be coveted but an innocent young girl whose all-too-brief love affair caused her ultimate downfall.

There are also other original visual clues within the work that reveal the point of narrative being depicted: Hero’s torch indicates that it is at night when she is expecting Leander, while the seashells on the base tell us that she is on the beach. The way her hair is blown back along her neck (when it likely should have hung down as in the Juno Ludovisi) as well as the angle of the flames could indicate a high wind, placing her outside during a storm. In conclusion, it is clear that Story did his research on the subject. He incorporated elements from numerous versions: Musaeus’ account of Hero’s final moments, Ovid’s and Hunt’s descriptions of her psychological trauma, and details of her raiment and physical appearance that lend an air of historical authenticity. Yet she also stands apart from the crowd through her presence on the shore (as opposed to her tower) and the conspicuous absence of Leander. Hero Looking for Leander may be one of Story’s earliest ideal creations, but it is also a herald of what would become the hallmark of his success: ideal women of antiquity made relatable—and, above all, human—through intense emotion.

—Kira Jones, Emory University, Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Graduate Fellowship Program in Object-Centered Curatorial Research, 2014

Selected Bibliography

Atelier. “Foreign Correspondence.” Cosmopolitan Art Journal 1, no. 4 (June 1857): 121–22.

The Berg Collection of English and American Literature. The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.

D’Ossat, Matilde De Angelis, Daniela Candilio, and Eugenio Monti. Scultura antica in Palazzo Altemps. Milan: Electa, 2002.

Greenthal, Kathryn, Paula M. Kozol, and Jan Seidler Ramirez. American Figurative Sculpture in the Museum of Fine Arts Boston. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1986.

Hawthorne, Nathaniel. The French and Italian Notebooks. Ed. Thomas Woodson. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1980.

Hunt, Leigh. The Poetical Works of Leigh Hunt. Edited by H. S. Milford. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1923.

———. “Six Letters addressed to W. W. Story, 1850–1856.” Bulletin and Review of the Keats-Shelley Memorial, Rome 2 (1913): 78–92.

James, Henry. William Wetmore Story and His Friends. 2 vols. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1903.

Keats, John. The Poetical Works and Other Writings of John Keats. Edited by H. Buxton. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1895.

Marlowe, Christopher, and George Chapman. Hero and Leander. London: Edward Blount, 1598.

Musaeus. Hero and Leander: A Poem. Translated by Edward Burnaby Greene. London: J. Ridley, 1773.

“News of Tite.” London Spectator. January 24, 1863.

Ovid. Heroides and Amores. Translated by Grant Showerman. Loeb Classical Library Volume 41. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; London: William Heinemann, Ltd., 1931.

Phillips, Mary E. Reminiscences of William Wetmore Story, the American Sculptor and Author. Chicago: Rand McNally, 1897.

Ramirez, Jan Seidler. “A Critical Reappraisal of the Career of William Wetmore Story (1819–1895), American Sculptor and Man of Letters.” PhD diss., Boston University, 1985.

Scott, Leonora Cranch. The Life and Letters of Christopher Pearse Cranch. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1917.

Story Family Papers. Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin.

Story, William Wetmore. Conversations in a Studio. 2 vols. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, and Company, 1890.

———. Graffiti d’Italia. New York: Scribner, 1868.

———. Roba di Roma. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, and Company, 1862.

Tolles, Thayer, Lauretta Dimmick, and Donna K. Hassler. American Sculpture in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Vol. 1, A Catalogue of Works by Artists Born before 1865. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1999.

“William W. Story and His Cleopatra.” Dwight’s Journal of Music. July 28, 1860, 141.