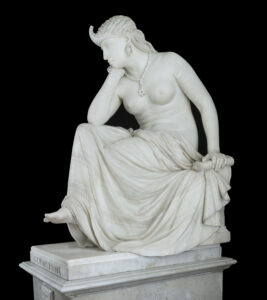

William Wetmore Story (American, 1819–1895), Medea, 1866, marble, 76 1/4 x 27 1/4 x 26 1/4 inches. High Museum of Art, gift of the West Foundation in honor of Gudmund Vigtel and Michael E. Shapiro, 2010.91. Photo by Almont Green.

William Wetmore Story was born on February 12, 1819, the second son and sixth child of Supreme Court Judge Joseph Story and Sarah Waldo Wetmore. Although he is best known for his sculptural works, Story was also a noted poet, author, intellectual, playwright, and lawyer, having begun his adult life as a graduate of Harvard Law. By the time of his father’s death in 1845, he had already modeled a portrait bust of his father that was so well received that Judge Story himself sent it to be displayed at Harvard. It is perhaps no surprise then that William Wetmore Story won the commission for his father’s memorial statue from Mount Auburn Cemetery. The two years he spent in Europe cultivating his tastes in preparation for the memorial would cement his desire to pursue a career as an artist, leading him to move himself and his family back to Rome permanently in 1850.

During his time in Rome, Story’s apartments in the Palazzo Barberini became the center of the artistic, literary, and scholastic circles for expatriates in the city. He was close friends with such celebrities as the Brownings, Leigh Hunt, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Harriet Hosmer, and Charles Sumner, to name but a few, and it was Pope Pius IX himself who sponsored the inclusion of Story’s monumental Cleopatra and Libyan Sibyl in the 1862 International Exhibition in London. Story continued to work in Rome until the death of his beloved wife, Emelyn, in 1894. After completing his last sculpture, the Angel of Grief (fig. 1), in honor of his wife, he soon moved to Vallombrosa, southeast of Florence, with his daughter Edith and died in 1896. He is buried with Emelyn under the Angel of Grief in the Protestant Cemetery in Rome.

Description

The High Museum of Art’s Medea (fig. 2) forms part of one of the largest collections of William Wetmore Story’s ideal works in the United States and represents the height of his career as an internationally renowned sculptor. Like many of his ideal works, Medea depicts a psychologically charged moment from mythology—in this case, the moment when Medea (famed Colchian sorceress who aided and later married the Greek hero Jason) has resolved to murder her two young sons in order to exact revenge on her husband.

Medea is fully clothed although in the Hellenistic Greek tradition of sculpted “wet drapery” (where the folds of the garment are carved in such a way as to accentuate anatomy while still remaining within the bounds of propriety). She wears a classical chiton with half-sleeves buttoned at the side and a zone, or girdle, around her waist. Her mantle, or himation, drapes around her hips and is distinguished from the chiton by thicker folds and a very low-relief border of palmettes (suspiciously similar to Story’s own monograph) around the bottom edge.

She stands in contrapposto, her right leg extended forward to rest just over the edge of the square base while her right recedes behind the layers of fabric, with only her sandaled foot visible. Her head is bowed forward but not quite resting on her left hand, which she holds close to her breast in a gesture of deep thought. The right arm crosses over her abdomen and grasps a dagger.

The full artistic force of Medea is certainly best felt from the front, where one can clearly view her furrowed brow and steely resolve. The strong diagonal created by her extended leg draws the eye first to her dagger, resting on her hip, and then up through her crooked left elbow to rest at last upon her frightful expression. Even if one does not know her story, the statue’s composition leaves no doubt as to the eventual end. Approaching the statue from other directions, however, leads one through a much more gradual discovery that, I would argue, reflects the buildup of dramatic tension of which Story was so fond in music and theatre.

For example, approaching from the right side of the statue leaves both the dagger and most of the figure’s expression obscured. Medea becomes a simple woman in classical dress who is, admittedly, deep in thought but whose body language does not invite questioning. Rather than leading the gaze upward, her extended leg and right arm create a wall. The viewer is instead drawn around the back by the folds of her himation, curving from the floor up to her left hip, and the thinner fabric of her chiton, which likewise follows the contours of her body. Circling around behind her, the viewer can now see the tip of the dagger, but as her face is now completely obscured, its purpose remains unknown. Only when following the terraced lines of her himation around to view her from the front is her full, terrible intention revealed.

Provenance

As stated in a letter to his friend Charles Sumner, Story first considered modeling a Medea in 1864.1 He quickly acted on his idea and had blocked out the figure in marble by June of 1865.2 This statue was completed in 1866 and purchased by William H. Stone of London, where it entered into the collection of the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths in 1896 and was displayed in the main hall along with copies of Story’s Cleopatra (fig. 3) and The Libyan Sibyl (fig. 4). The three statues remained with the Goldsmiths for quite some time, although they were eventually moved to a storage area where they suffered damage during the London blitzkrieg of World War II (specifically, Medea’s dagger was broken). Medea was sold at a Christie’s auction in November 1982, soon after which it was acquired by the West Foundation (along with Cleopatra and The Libyan Sibyl) and currently resides at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta.

Medea was immediately met with high acclaim, such as Katharine C. Walker’s review in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. She raves: “[W]e had the privilege of entering the innermost studio, and seeing the sculptor, moulding-stick in hand. Even in its immaturity and in soulless plaster we saw in the Medea a grander statue than those apt fingers had previously created.”3 Indeed, Medea proved to be one of Story’s more popular works, as there are three other known life-size reproductions and one under-life-size reproduction. The first of these was commissioned in 1867 by one W. Dudley Pickman and acquired by Salem’s Peabody Essex Museum in 1898.4 By this time, Story had altered the drapery to create more severe folds and a straighter line along the bottom edge from her right hip to her left. Story also changed the base of the statue so that instead of standing on a simple, roughened floor, Medea was on a diamond-patterned floor, reflective of ancient floor mosaics.

The second copy—commissioned in 1868 by an American named William T. Blodgett, who sold it to Henry Chauncey—reflects the changes to drapery and base that Story had effected in 1867. Chauncey loaned Medea to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York for an exhibition in 1874, where it gained a permanent home in 1894 (fig. 5). The last full-size copy was created sometime between 1868 and 1876 and remained in Story’s possession until his death in 1896, at which point his son Waldo donated it, along with quite a few other works, to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston (fig. 6). This particular copy was exhibited in Philadelphia during the Centennial Exposition of 1876. Despite a laudatory reception and receiving a medal for artistic excellence, Story was by all accounts unhappy with the Exposition, not least of all because the dagger was broken by overzealous viewers. He was also unhappy with the display, complaining to Mr. Field that they had “put it in a room with a spotlight directly over her head, with the sun entering by the door. She was therefore illuminated by reflection from the floor.”5 The public seems not to have minded, though, as it was certainly one of Story’s more successful American showings.

The execution of this particular copy is unusual in that it seems to represent a middle ground between the 1865 original and the 1867 update. The base is similar to that of the original in that it has a plain, roughened surface, but the title is flush with the surface, as opposed to being raised, as on the High’s version. The overall shape is somewhat different, however, as the edges of the square have been clipped. The drapery around the figure’s hips follows the severe diagonal of the later versions.

A recently discovered copy is an under-life-size version dated to 1876, when Story’s personal copy was on display at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. It features the clipped-square base of the Boston copy, although the drapery is much closer to that of the 1865 original. The title uses the same block letters as the other versions but is flush with the surface, as in the other copies. It does not, however, use the mosaic flooring present in the Peabody and Met versions. The copy was sold in a 2015 Sotheby’s auction and is currently the only small version of Story’s Medea that is known.

Inspiration and Influence

While most people are familiar with Medea through Euripides’ fifth-century Greek tragedy of the same name, she was present in classical mythology long before that. She does not appear in Homer but is mentioned in Hesiod’s Theogony (992–1002) as the highly desirable and semidivine woman who marries Jason and bears his heir. Pindar also mentions her briefly in his Pythian Odes, written much later (around 470 BCE) and casts her as the victim of both Jason’s charm and the machinations of his divine patrons (Py. 4.211–19). In Hesiod, she is a prize to be won by the victorious hero, while Pindar casts her in the role of a woman used by said hero to accomplish some vital task and then be cast aside. While Story was undoubtedly aware of them, neither of these versions seems to have affected his own artistic vision of Medea.

The version of Medea that Story immortalized in marble is that of a ruthless, conniving sorceress who will stop at nothing for revenge. This is certainly the description people have been most familiar with for centuries. Strikingly, the crime for which she is most famous—namely, murdering her own children—seems to have been an invention of Euripides that took off after his debut and rapidly became canon.

Euripides’ Medea, first performed in 431 BCE for the City Dionysia, a dramatic festival in Athens, centers on the aftermath of the voyage of the Argonauts and our mythical couple’s arrival in Corinth. As a child, Jason was the displaced heir to the throne of Iolcos, which had been claimed by his uncle Pelias. As an adult he returned to claim his birthright and was told that if he wanted the throne, he must bring back the Golden Fleece from the distant island of Colchis in the Black Sea. Jason accepted the challenge and, with the help of the goddesses Hera and Athena, built a ship and secured the aid of the most legendary heroes of Greece.

Despite his lack of leadership abilities or even heroic qualities, Jason somehow managed to make it to Colchis, where he won the affection of the king’s daughter, Medea. Whether inspired by some divine intervention or simply the irresistible charm of a Greek hero, Medea soon fell in love with Jason and endeavored to do everything in her power to keep him alive. As a sorceress and priestess of the underworld goddess Hecate, she was more than a match for the trials her father threw at Jason, and in return for her help Jason promised to marry her and take her back to Greece with him.

Jason succeeded in obtaining the fleece, and the Argonauts quickly fled. The time between their flight from Colchis and arrival in Corinth was not without strife, however. They were pursued by King Aeetes and resorted to killing Medea’s brother (his age varies with the source; some maintain that he was an adult, while others claim that he was a child whom Medea had brought as a hostage to ensure their safety) and scattering his body parts in the sea so Aeetes would be forced to stop and fish them out in order to provide a proper burial. Murder outside of the contexts of war was a serious matter in the ancient world, and so they had to seek purification before proceeding on to Iolcos.

King Pelias was not eager to relinquish the throne, though, in spite of his earlier promise and Jason’s possession of the Golden Fleece. Medea once again used her sorcery to his benefit and convinced Pelias’ daughters that if they chopped him up and placed his body parts in a cauldron then his youth would be restored to him. Needless to say, Pelias did not survive, and Medea and Jason were soon cast out of Iolcos. They proceeded to Corinth, where Euripides’ tragedy picks up.

While in Corinth, Jason woos Creusa, the king’s daughter, and makes plans to wed her. While the king is supportive of this, Medea, naturally, is not and soon faces the prospect of exile in a hostile land. While the Medea is undoubtedly a tragedy, it is unclear who the victim is; in spite of her horrific acts, Medea is the natural person to sympathize with. Jason is portrayed as a boor who takes all the credit for his heroic adventures and none of the blame for the sacrifices and often terrible acts (such as Medea betraying her father, killing her brother, or initiating the murder of King Pelias by his own daughters) that secured his victory. In fact, his argument to Medea is that she should be grateful he brought her to the civilized utopia that was Greece and that his marrying a princess and abandoning her were in everyone’s best interests.

Naturally, Medea disagrees and sets about plotting revenge. She first secures safe haven with Aegeus, King of Athens, who swears a holy vow to defend her from anyone after she arrives in his city. She then sends Creusa a poisoned robe, killing her, and stabs her two sons in the ensuing riot before flying off in a dragon chariot granted her by her grandfather Helios (the sun god) and settling in Athens. In doing so, Medea has effectively condemned Jason to the same fate he would have had her suffer while at the same time destroying any legacy he might have had left. Without his children, he has no heirs and no way to continue his family line; without his new wife, he has neither the security of a royal position nor the promise of future heirs. Without Medea, his own inadequacies come to light and he is unable to create a new heroic legacy. As she says in her final moments before flying to Athens: “You, as is right, will die without distinction, struck on the head by a piece of the Argo’s timber, and you will have seen the bitter end of my love.”6 In stripping him of his future, Medea leaves Jason with nothing but his heroic legacy, symbolically rotting, and his bitter memories.

The other major literary work of the ancient world concerning Medea is a tragedy by Seneca, a late first-century Roman working under the Emperor Nero. It follows the same basic plot as that of Euripides: Medea and Jason have reached Greece after their adventures on the Argo, and Jason is in Corinth, planning to wed Creusa. However, it differs in two important matters. First, Jason is apparently forced by Creon to set Medea aside in favor of Creusa. Secondly, Medea is much more vitriolic in Seneca’s version and reveals her terrible rage when she summons all the demons and powers of the underworld to poison the robe that she plans to send to Creusa. Here, too, she slays her own children, although her conviction wavers right up until the last moment.

The slaughter of children by their mother’s hand is undoubtedly the most memorable moment in Medea’s story and was just as shocking to ancient audiences as it is to modern ones. Some sources seek other explanations for their death, such as the scholia for Euripides’ Medea, which has the children killed by a Corinthian mob as vengeance for the murder of their princess. Pausanias, too, has a different version, wherein Medea leaves them at a temple of Hera in the belief that the goddess will grant them immortality. Unfortunately, she is mistaken, and the children die.

Modern retellings may also seek to explain how a mother could do something so heinous as to stab her sons to death, as is the case with Ernest Legouvé’s Médée. The tragedy, which premiered in Paris in 1856, was met with great acclaim both in Paris and abroad. Legouvé had originally written the part of Medea for Madame Rachel, one of the most famous tragedians of the nineteenth century. She dropped out of the production during rehearsals, however, which left Legouvé to find a new leading lady. He approached Adelaide Ristori, an Italian-born actress then residing in Paris, in hopes that she would take up the role.

As she recounts in her memoirs, Ristori was happy to receive him but informed Legouvé in no uncertain terms that she would not be joining the production. She had already been approached numerous times to play Medea in other adaptations but had refused each time, citing a strong maternal instinct that would prevent her from playing so dreadful a heroine, even in the name of her craft. Legouvé left the manuscript with her in the hope that she would read it and reconsider, however, and she soon became so engrossed with his work that she agreed wholeheartedly.

Legouvé’s Medea does not travel to Corinth with Jason; rather, he has already abandoned her and the children, and she happens upon them quite by accident. The first person she meets is Creusa, who is preparing for her marriage and receives both the children and Medea with grace. Orpheus, the famous Greek bard who played his lyre so beautifully that all the birds and beasts of the Earth would lie down to listen to him, appears as the voice of reason throughout the play and frequently sides with Medea by chastising Jason for abandoning her.

Legouvé’s Jason is, if possible, even more of a boor than in Euripides. Not only has he left Medea and his children wondering if he is alive or dead, but he has made himself at home in Corinth, ridding the area of monsters and courting the king’s daughter, Creusa. He loves her because she is young, virginal, and innocent—all the things that Medea is no longer. While he had initially abandoned his children along with his wife, seeing them again awakens his paternal feelings and he allows them to stay, provided that Medea herself is exiled. The ending is the same, however; Creusa and the children die by Medea’s design, and Jason is left destitute.

Legouvé handles Medea’s crime delicately, sensitive both to the dramatic impact that such an action has as well as the sensibilities of his Victorian audience. Miraculously, he had “discovered a way to make the killing of the children appear both justifiable and necessary,” a fact that undoubtedly aided in Ristori’s decision to take up the leading role. Her affection for her children is apparent throughout the play, and though her anger occasionally scares them, it is not until they choose to stay with Creusa (largely because she offers them a life of royalty instead of exile) that she resolves to kill them. By the end of the play, however, they have reconciled with their mother and it is to prevent them from being taken away from her by the Corinthian mob that she follows through with her original plan.

Ristori’s portrayal of Medea in this tragedy would go on to become one of her most memorable, and she took the preparation seriously: “I endeavored to express the character of Medea in the best possible manner, carrying myself back to antiquity in order to incarnate the impressions of those times, and I am justified in saying that I understood it as well as I should, or could.”7 Elsewhere she admits to channeling ancient sculpture, such as the Niobe group from Florence, which antiquarians including Story undoubtedly would have recognized and appreciated.

Story never outright declares where he got the idea for a Medea statue, but his admiration for Adelaide Ristori’s performance is clear: “[Ristori] excels in the representation of the more womanly and gentle qualities. Her acting is more of the heart—love, sorrow, noble indignation, passionate desire, heroic fortitude, she expresses admirably.… The terrible parts of Myrra and Medea she softens by the constant presence of a deep sorrow and longing. The horror of the deed is obscured by the pathos of the acting and the exigencies of the circumstances … [she is] driven to by violent impulses beyond her power to control. Her Medea is as affecting as it is terrible.”8 Story continued to be a follower of Ristori’s throughout her career, and the two became friends, with Ristori even penning him a heartfelt letter of sympathy upon the death of his wife in 1894.

Contemporaries were aware of Story’s fondness for her, saying that he “followed Ristori like her shadow, and has appropriated the great tragedienne’s inspiration as a spiritual body for his own.”9 Many modern scholars have also cited the passage in Roba di Roma as proof that Ristori was a fundamental influence in the conception of Story’s Medea, and the timeline would certainly suggest that as well.10 Roba di Roma was published in 1863 and the Medea finished in 1866, meaning that Ristori’s performance would certainly have been known to Story when he was conceptualizing the piece. Legouvé’s tragedy debuted in 1855, however, and there is no telling how early he saw the production. Furthermore, his description of her performance is not in the context of his own work but rather the state of the dramatic arts at that time in Rome. His laudatory comments concerning her portrayal (“violent impulses beyond her control,” “affecting as she is terrible”) apply just as much to the general character of Medea as represented in classical mythology, drama, and art as to Ristori’s specific performance and the qualities he admired in her acting. The fact that these comments apply to both Story’s depiction in marble and Ristori’s interpretation onstage simply confirms that they both did their mythological homework.

Of course, to say that Story got his inspiration from any one source alone is overly simplistic. He was a poet, musician, prose author, scholar, and classicist in addition to his main vocation as a sculptor, and once he got an idea into his head for a new artistic piece it would often spill into all of the various fields he practiced. For example, a collection of his poetry published in 1868 contains a work called “Cassandra,” after the mythical Trojan princess who was cursed by Apollo always to prophesize truly but never to be believed. In this poem, Cassandra is narrating her visions and catches a glimpse of Medea in her rage:

What dreadful crime? What does Medea there

In that dim chamber? See on her dark face

And serpent brow, rage, fury, love, despair!

What seeks she? There her children are at play

Laughing and talking. Not so fierce, I say,

You scare them with that passionate embrace!

Hark to those footsteps in the hall—the loud

Clear voice of Jason heard above the crowd.

Why does she push them now so stern away

And listening glance around,—then fixed and mute,

Her brow shut down, her mouth irresolute,

Her thin hands twitching at her robes the while,

As with some fearful purpose does she stand?

Why that triumphant glance—that hideous smile—

That pomard hidden in her mantle there,

That through the dropping folds now darts its gleam?

Oh Gods! oh, all ye Gods! hold back her hand.

Spare them! oh, spare them! oh, Medea, spare!

You will not, dare not! ah, that sharp shrill scream!

Ah!—the red blood—’tis trickling down the floor!

Help! help! oh, hide me! Let me see no more!11

This passage reflects all the qualities Story had praised in the Roba di Roma: rage, fury, love, and uncontrollable passions. Her “shut down brow … mouth irresolute … pomard hidden in her mantle” clearly reflect his sculptural composition, yet the setting is different from the Legouvé production that supposedly inspired him. Legouvé places both Medea and her children at an altar of Saturn, where the Corinthian mob surrounds them and hides the heinous deed. Here Medea is alone in a darkened room while her children play nearby. Jason is close, as is the crowd, which presumably indicates the Corinthian mob, but though they can be heard they are not in the same scene. In fact, the picture Story paints here is much closer to that of ancient Roman frescoes than any contemporary influence.

The statue’s similarity to ancient works has been noted by many scholars, and it is here that the notion of plagiarism amongst neoclassicist sculptors must be addressed. As Albert Gardner has said of the neoclassicists, “to the close student of classical sculpture their works appear to be little more than syncretic monstrosities composed of recognizable fragments from the less publicized artistic remains of Greece and Rome. Here, for instance, among the works of William Story, is Medea, a draped standing figure ‘lifted’ from a Pompeian fresco, its head, however, stolen from a masculine portrait bust of a different period.”12 The lack of originality in this artistic movement has been a well-worn theme in scholarship almost since the movement ceased and is beyond this project’s scope. However, as it pertains to Story’s Medea, Gardner’s criticism is overly simplistic and discounts both Story’s integrity as an artist and the tradition he was tapping into.

To begin with, saying that Medea’s head was based on an unnamed male portrait bust is simply ridiculous. Medea possesses none of the trademarks of ancient portraiture, male or female, that would support such an accusation. While it is true that she follows in the tradition of idealized classical beauty, she is just that: an idealized figure. Her hairstyle is typical of women in ancient Greek art and, if anything, recalls the Aphrodite of Knidos type with her double hair bands and wavy locks (fig. 7). Her face would fit in with any of the countless idealized goddesses, korai, and matrons of the classical tradition and is remarkable only in that it shows emotion. While one could argue a certain similarity between her and, say, a work of Polykleitos, that is more the result of a sculptural canon of idealized proportions than any lack of artistry on Story’s part.

As for the Pompeian fresco, there is a series of them from the Roman cities around the Bay of Naples. The first of these is a fresco from the Augusteum in Herculaneum, which was destroyed during the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 CE. It was excavated in the late eighteenth century and would certainly have been known by Story, if not firsthand during his trips through Italy then second-hand through publication. In this work, Medea is leaning against a wall peering anxiously around the corner, her indecision and anguish plainly visible in her pursed mouth and knotted brow. Her left leg is extended slightly forward, and she clasps an elaborate dagger in her hands. While her children would have undoubtedly been present in the original context, she was excised from the scene at some point after excavation and is now a solitary figure.

The second fresco, which is likely the one Gardner had in mind, hails from the House of the Dioscurii in nearby Pompeii. This one is much more complete and has Medea standing to the right, again in contrapposto with her left foot forward and her right arm stretched across her torso, resting on top of a sword held in her other hand. Much as in the Herculaneum example, her brows are drawn together in worry as she gazes behind her at her two children, engaged in a game of knucklebones. Both frescoes were likely based on a famous painting by the Greek artist Timomachus, which was brought to Rome by Julius Caesar and kept in the Temple of Venus Genetrix until its destruction in 80 CE. The appearance of the original is known from accounts by various ancient authors, and it was this moment, when Medea is contemplating her crime but has not yet committed it, that would become a hallmark of Roman representations of her.

Just as there are differences between these two frescoes, despite being based on the same original work, there are also significant differences between the frescoes and Story’s Medea that dispel Gardner’s accusation of “lifting” the pose directly from antiquity. Both frescoes have Medea looking to the side rather than bowing her head in thought, and neither shows her with a hand brought up to her chin. Her himation is bundled around her hips instead of draping down to the floor; additionally, while she is visibly caught between indecision and distress in the Roman works, Story depicts her as resolved in her course of action. He was certainly conscious of these ancient representations of his subject but rather than stealing the composition from antiquity because he lacked the ingenuity to invent a new one, he recalled well-known classical examples and then cunningly modified them to reflect a different facet of Medea’s personality.

The similarities in pose and attitude between these Roman frescoes and Story’s Medea are clear, but he may have gotten the idea for his composition as early as 1848. A quick drawing in a small sketchbook he used during his travels through Italy and Germany in 1848 and 1849 shows a Greek woman in a very similar contrapposto pose, with the right foot positioned forward of the left and the drapery curling up over it.13 She rests her chin on her left hand while crossing the right arm over her abdomen. The features are blank, and there is no sign of a dagger, but the general form is unmistakably that of the 1865 Medea. Notably, this was at least six years before Adelaide Ristori’s performance as Medea and suggests that while she may have influenced the feeling of the piece, he certainly had other inspirations for the form.

Another notable example comes from a Roman-period funerary relief which itself copies a scene from the Altar of Pity in the Athenian Agora.14 Here Medea faces frontally and rests her head on her right hand, supported in turn by the left, which she crosses over her torso. Her left leg is once again positioned forward, and she holds an item in her right hand that later copies reveal to be a leafy plant. Her children are nowhere to be seen, however, as this depicts a different scene from her life: the moment when she convinces the daughters of Pelias that they could rejuvenate him by murdering him and placing the dismembered corpse in a cauldron. Unlike in the Roman frescoes, her face is idealized and devoid of expression. Story would have had ample opportunity to study the Roman copy housed in the Vatican Museum and also may have seen the other copy in Berlin during his travels through Germany in 1849.

Modern Criticisms

Apart from the criticism involved with imitating ancient works, which we have already discussed, Story was chided for his “book-culture” and insistence on referencing narrative in art. Some critics, including those at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition, initially praised the literary interpretation, saying that “the unmistakable seal of book-culture on a work of art will always make it interesting to literary people; and Mr. Story’s Medea … [is] overgrown with this creeping feeling of legend and tradition: no ignorant, unread man would ever have conceived them so.”15 The catalog goes on, however, to note how the art lover first looks at technique and finds nothing especially noteworthy in Story’s Medea. Henry James was also of the opinion that Story’s numerous areas of interest negatively affected his mastery of sculptural technique, as his many passions in life prevented him from devoting the necessary focus to sculpture alone.16

A similar complaint was Story’s use of props, which some felt detracted from the artistic integrity of his compositions. James wrote that “his imagination, of necessity, went in preference to the figure for which accessories were of the essence; which is doubtless a proof, one must hasten to recognize, that he was not with the last intensity a sculptor.”17 John Rowe contextualizes this quote about Medea, “whose thoughtful pose is balanced by the dagger she grips in her right hand as a somewhat gimmicky comment on just what she is planning.”18 What one must realize here, however, is that while some have defined artistic excellence by the absence of distracting elements from other disciplines (such as narrative or props), Story himself did not recognize dividing lines between his interests. On the contrary, he considered all his various pursuits, whether scholastic, literary, dramatic, or sculptural, to be expressions of the same artistic ideal. He himself wrote that, “in art … as much as in law, it seems to me that culture and a large education are almost necessary to create a great artist. In ancient days, as well as at the period of the Renaissance, the great artists were accomplished in various branches of art and did not confine themselves to one.”19 Story meant his works to have a narrative component and brought all of his talents to bear on every project. He would often sit at the piano and play while he was conceptualizing a new piece and did extensive research for his historical works.

Medea, for example, is not only depicted in accurate ancient dress (as discussed above) but also wears accessories that would be easily recognizable to anyone familiar with archaeology. The snake bracelet winding around her left wrist is almost identical to those worn by women in ancient Rome, and her ornate beaded necklace likewise would fit in among the archaeological finds of the classical world. Story’s attention to detail in historical costume was something he was praised for by his contemporaries and something whose absence he considered a cardinal sin in the works of other artists. As for being bookish in his insistence on a literary component, Story is not only following his own beliefs in what good art should encompass but an established ancient tradition as well. Much of the classical art he had studied, especially the myth-based examples, made liberal use of iconography. In societies where literacy amongst the masses was questionable at best, the dissemination of mythology was primarily through imagery and oral tradition. An average Greek person may not have seen Euripides’ tragedy and certainly wouldn’t have read it, but he would have known the story of Medea and could comprehend the meaning of a scene depicting an angry, meditating woman holding a dagger. By using the same system of iconographic attributes, Story ensures that anyone familiar with Medea’s myth can recognize the subject of his statue. Likewise, even without knowing the whole story, his cunning use of props, placement, and emotion give the viewer enough clues to piece together the major components of the plot and still come away with a good understanding of the work.

The last major criticism deals with Story’s choice of subject and execution. Joy Kasson, in seeking to place neoclassical sculptures of women within the rhetoric of defining womanhood during the nineteenth century, alleges that Story “evoked images of dangerous female passions only to affirm that they could be contained and controlled.”20 She notes Story’s predilection for portraying powerful, dangerous women in his ideal sculptures and argues that by capturing them in marble he was playing to a nineteenth-century anxiety about the proper place of women in society. Women such as Medea, along with Cleopatra, Delilah, and Sappho, exhibited “dangerous female passions” in a safe manner that could be viewed and rationalized by the audience. Much of Kasson’s argument is based on contemporary reactions to ideal female sculpture and discussions on the role and viewing of art in the nineteenth century, however, and reads heavily into the motives of both Story’s audience and his own artistic intentions without delving much into either the narrative behind the piece itself or Story’s own writings.

For example, when discussing Edward Everett Hale’s description of Story’s studio, she states that, for him, “the tale it told, rather than the visual pleasure it offered, was the chief attraction of Story’s sculpture. And that tale was one of female power rendered powerless by historical change.”21 The first part of her statement brooks no argument, as Hale states that himself. As far as the narrative of Story’s sculptures being one of “female power rendered powerless by historical change,” it is an exaggeration at best and neglects all the psychologically charged ideal men he sculpted, including Orpheus, Saul, and King Lear.

Taking Medea as an example, Kasson begins her argument by stating that “Story’s special talent for evoking, only to deny, the possibility of woman’s demonic power can be seen clearly in a statue that resonated deeply with nineteenth-century anxieties about both women and the family, Medea.”22 It is safe to assume that Medea’s tale had a shocking effect on nineteenth-century audiences, as it had in antiquity and as it continues to do today. Yet, there is no reason to say that Medea’s “demonic power” is being denied here, nor that she is being “rendered powerless by historical change.” Story does not show her in the midst of the act, nor does he show her as a terrifyingly powerful sorceress calling upon eldritch gods to aid her in revenge. Instead, we are faced with the moment when she resolves to take her fate into her own hands, whatever the cost.

Kasson also fails to account for the rest of the narrative power on which she places so much importance. Medea was never a woman who was rendered powerless; on the contrary, she is the most powerful character throughout the various iterations of her myth, and none of them ever indicates that she was punished for her transgressions. In Euripides, she cunningly secured sanctuary with Aegeus, King of Athens, before slaying her children and flying off to join him in a dragon chariot while at the same time leaving Jason destitute in Corinth. Seneca and Legouvé do not resolve the situation, perhaps considering that Euripides’ version had done so already, but both of their tragedies leave Medea with the last word as she forces Jason to take responsibility for his ill treatment of her. These are the narratives Story was working from and that his educated audience would have been familiar with, and they all portray Medea as the opposite of what Kasson is trying to make her out to be: a strong, independent, powerful woman. While certain contemporary publications, such as the Philadelphia Exposition catalogue, prefer to gloss over this fact and construct narratives wherein Medea was framed by the Corinthians, this is only the work of one scholar and cannot be taken as indicative of either the general public understanding or Story’s own intentions.23 At any rate, his complaints about the Exposition’s staging make it clear that he did not have much say in the event and that he regretted sending Medea there. Kasson’s concluding remark, that “to further contain the unsettling implications of the sculpture’s subject, viewers at the Centennial Exhibition devised their own form of audience response. Vandals attacked the dagger, symbol of Medea’s murderous—and specifically phallic—power, defacing the sculpture by breaking it off” is yet another example of sensationalizing an account without considering all of the surrounding circumstances.24 She cites only the Exposition catalogue, which simply states that the dagger was broken as an unfortunate accident, and fails to mention the crowds that would have been present or the lack of protection for the statue. She is also seemingly unaware that the dagger was produced separately from the rest of the statue, is the most fragile part of the work, and is therefore the most likely to break (as it has on the High version, while in London during World War Two).

—Kira Jones, Emory University, Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Graduate Fellowship Program in Object-Centered Curatorial Research, 2014

Selected Bibliography

Charles Sumner Papers. Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Euripides. “Medea.” In The Complete Greek Tragedies, Vol. 3. Edited by David Grene and Richmond Lattimore. Translated by Rex Warner. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992.

Gantz, Timothy. Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources. 2 vols. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996.

Gardner, Albert Ten Eyck. Yankee Stonecutters: The First American School of Sculpture, 1800–1850. New York: Colombia University Press, 1945.

Greenthal, Kathryn, Paula M. Kozol, and Jan Seidler Ramirez. American Figurative Sculpture in the Museum of Fine Arts Boston. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1986.

James, Henry. William Wetmore Story and His Friends. 2 vols. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1903.

Kasson, Joy. Marble Queens and Captives: Women in Nineteenth-Century American Sculpture. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990.

Legouvé, Ernest. Medea: A Tragedy in Three Acts. Translated from the Italian version of Joseph Mintanelli, by Thomas Williams. New York: John A. Gray & Green, 1867.

Phillips, Mary E. Reminiscences of William Wetmore Story, the American Sculptor and Author. Chicago: Rand McNally, 1897.

Ramirez, Jan Seidler. “A Critical Reappraisal of the Career of William Wetmore Story (1819–1895), American Sculptor and Man of Letters.” PhD diss., Boston University, 1985.

Ristori, Adelaide. Studies and Memoirs: An Autobiography. Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1888.

Rowe, John Carlos. “Hawthorne’s Ghost in James’s Italy: Sculptural Form, Romantic Narrative, and the Function of Sexuality in The Marble Faun, ‘Adina,’ and William Wetmore Story and His Friends.” In Roman Holidays: American Writers and Artists in Nineteenth-Century Italy. Edited by Robert K. Martin and Leland S. Person. Iowa City: University of Iowa, 2002.

Seneca. “Medea.” In Seneca’s Tragedies. 2 vols. Translated by Frank Justus Miller. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1938.

Shin, Earl, Walter Smith, and Joseph M. Wilson. The Masterpieces of the Centennial International Exhibition Illustrated. Vol. 1. Philadelphia: Gebbie & Barrie, 1876.

Story Family Papers. Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin.

Story, William Wetmore. Conversations in a Studio. 2 vols. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, and Company, 1890.

———. Graffiti d’Italia. New York: Scribner, 1868.

———. Roba di Roma. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, and Company, 1862.

Taft, Loredo. The History of American Sculpture. New addition with supplementary chapter by Adeline Adams. New York: Macmillan, 1930.

Tolles, Thayer, Lauretta Dimmick, and Donna K. Hassler. American Sculpture in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Vol. 1, A Catalogue of Works by Artists Born before 1865. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1999.

Walker, Katharine C. “American Studios in Rome and Florence.” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine 33 (June 1866): 101–105.